SAMPLE POSTS, [CMPR] Cimpress NV

[CMPR – Cimpress NV] Scale Economies and Hard Realities, Pt. 3

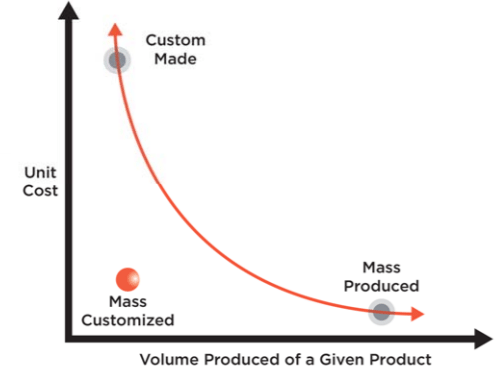

Cimpress is a fine business that has been in search of strategic direction for the last 6-7 years, groping for the right balance between value-added customization and low-cost production. These two sources of differentiation are often at odds because the scale economies required to claim a cost advantage depend on running lots and lots of volume across significant fixed costs, a process that is best suited for homogeneous products that share a common manufacturing base and process. You can imagine casting a single widget SKU over and over again. There are no incremental set-up costs from line changeovers. The assembly line just keeps humming as long as it can, spewing a stream of identical widgets onto a continuously flowing conveyor belt, the upfront cost of heavy equipment diffused over more and more manufactured units. At the other extreme, a stylist’s average cost per haircut stays roughly the same, whether he does 20 haircuts a day or 30. Of course, most jobs fall somewhere between these two poles. Cimpress (originally known as VistaPrint), which makes a variety of customized physical marketing materials – business cards, signage, apparel, gifts – for mostly micro business with fewer than 10 employees, claims that it can capture the benefits of both differentiation and low-cost (“mass customization”):

Source: Cimpress Business cards are a perfect use case for mass customization because from the customer’s perspective, a set of business cards, tatooed with a unique logo and font, is unique; but from Vistapint’s perspective, the core manufacturing process and materials required to produce them is essentially the same across all customers. And after its founding in 1995, Cimpress spent the first dozen or so years of its existence focused on paper-based products…business cards (where it remains dominant) postcards, brochures, presentation folders, data sheets, and the like, predominantly in North America. Volume brought scale, scale compressed average unit costs, profits from cost advantages funded VistaPrint’s strategy, which was to litter inboxes with cheesy marketing campaigns offering something like business cards or return address labels for free and drawing customers to the website, where they could then be cross-sold other products and bamboozled with exorbitant shipping costs on the check out page (after they’d already spent the time designing their items and were psychologically committed to the purchase).

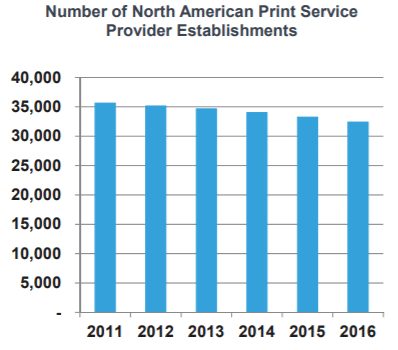

Today, Vistaprint prints 6bn business cards a year, one for nearly every person on the planet. It can produce a pack of business cards in less than 10 seconds and fulfill the order in less than 2 minutes. No one else comes anywhere close to extracting the scale economies enabled by that kind of volume. Although paper-based marketing, including business cards, is in decline, the company’s Vistaprint segment is still showing high-single/low double digit organic growth as it continues to steal share from the tens of thousands of small manual operations that still account for most of the putative $30bn market opportunity [per management; computed as 60mn small businesses with fewer than 10 employees across North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand multiplied by $500 in annual marketing spend], leaving Cimpress, with just $2.4bn of total revenue, plenty of runway ahead.

But sometime in 2011, with revenue growth decelerating, management embarked on an aggressive M&A strategy. Since fy11 (fiscal year ends June), on top of ~$590mn in capex and capitalized software development, management has spent around $900mn buying 15 companies – ranging from a DIY website building (Webs.com) to a host of European print and design companies catering to graphics professionals (consolidated as the “Upload and Print” operating segment) – tangentially related to the core Vistaprint business by dint of their marketing orientation but otherwise diffuse in terms of product SKUs and addressable markets. And for this ~$1.5bn investment, Cimpress’ EBITDA (after stock comp) has grown by just $106mn, a 7% pre-tax return compared to management’s 10% hurdle rate for predictable organic investments in developed countries and 25% bogey for riskier investments in emerging markets. Now, one might argue that the cost structure is larded with growth opex that will eventually subside. But, we’ve also heard this line from management before, as it has fumbled its way from one strategy to the next.

The first course correction came in fy11, when management recognized that deep discounting, aggressive cross-selling, and cheap checkout tricks were compromising repeat purchase rates, diluting lifetime customer values, and attracting low quality customers looking for an easy deal…basically, a leaky bucket that required constant infusions of customer acquisition spend that management did not think was sustainable. And so, Cimpress made significant investments in packaging, product quality, and user experience on the site. It dramatically reduced what it charged customers for shipping, which at the time apparently made up a “very material portion of revenues”, and introduced less jarring discounts on more transparent list prices. These actions were meant to chase away the cheapskates who only cared about price, leaving the company with a more loyal and satisfied core more apt to repeat purchase. Didn’t really work. Despite some operational improvements – quality complaints, production throughput times, late deliveries all improved – organic revenue growth slowed from 22% in fy11 to 20%, then 12%, then 4% over the subsequent 3 years. Gross margins declined a bit, EBITDA margins declined a lot. Buyer repeat rates actually declined from 30% to 26%. Management’s initial expectations for $5 EPS (representing 20% annual growth over 5 years) and $2bn in revenue by fy16, would clearly not come to pass. That brings us to Act II.

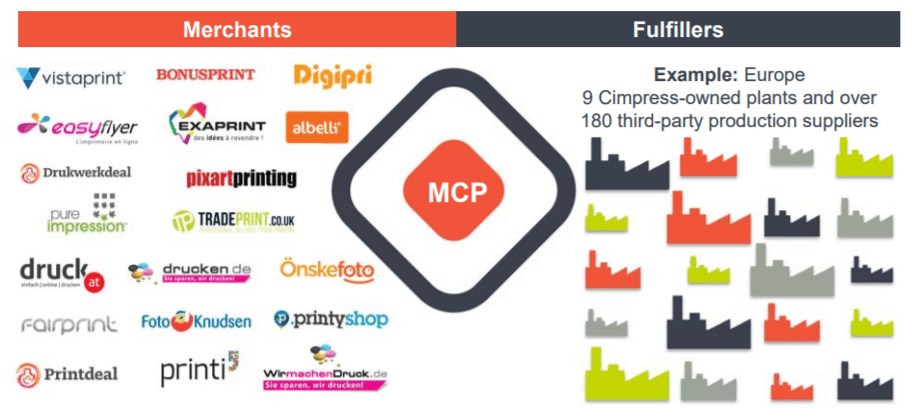

Sometime in fy13, the company embarked on an effort to disaggregate its tech platform into a set of software microservices appropriately named the Mass Customization Platform (MCP) as part of a broader effort to centralize all sorts kinds of functions – product management, order routing, fulfillment, commodities procurement – across its 20+ brands:

“…our vision for MCP is to be a constellation of modular, reusable and independently functioning software components and related services which is analogous to a well-organized set of interchangeable Lego blocks. This platform will sort millions of heterogeneous incoming orders into homogeneous specialized production streams which, thanks to the automated workflow and the regular repetitive production steps we can enable, will embody the principles of mass customization. Yet, the overall platform needs to remain reconfigurable and modular to ensure the relevance to a wide variety of applications….what we are doing is we are frankly trying to break the businesses which we bought, not just Vistaprint, but each of the individual companies we bought, into the component parts of the merchant, the customer-facing business unit with the brand and the fulfiller, and then to reconfigure all the IT systems so that those can…act as a routing layer between those.” – Robert Keane, Chairman and CEO (Cimpress Investor Day, 8/10/2016)

Management’s big idea was to create a matchmaking service that would pair the unique, specialized, and often small-sized manufacturing and fulfillment needs of its sprawling internal businesses (“merchants”) – some selling business cards to micro-businesses in the US, others serving graphic design pros in Europe who in turn serve micro-businesses – to its most cost effective option among a network of in-house and third party production plants and shipping/logistics providers. As the number of fulfillment partners joining the platform expanded, so too would the number of SKUs the company could offer, which in turn would attract still more fulfillment partners seeking production volumes to run through their specialized plants. Two-sided engagement would lift volumes flowing through Cimpress’ network, bringing procurement leverage to bear against service providers, equipment vendors, and commodities suppliers.

But just 5 months after promulgating this lofty vision during 2016 Investor Day, management conceded that this centralized model, which was intended to increase speed to market and production flexibility, had instead bogged down the company with complexity and bureaucracy. It announced plans to retreat back to a more decentralized organizational setup wherein production, fulfillment, and product management would be siloed once again by brand, though non-core corporate functions (finance, legal, major capital allocation), procurement, and the modularized technology platform would remain as shared services across banners. Now the thinking is that decentralization will unleash “entrepreneurial energy”, ensure accountability for results, and improve customer satisfaction. And that’s where we are today. Mistakes have been made, that much is clear. The company’s acquisition of DIY website builder Webs.com, one of it’s largest, seems particularly ill-conceived. Website building is a high gross margin business that pure-plays struggle to monetize because lofty customer acquisition costs eat up all the profits. But Cimpress believed it could do away with much of these advertising costs by cross-selling web services into its existing customer base, because in management’s own words “…a website is the same as a brochure, but it’s a digital version of that.”

But of course, a website is more than just another marketing tool that you toss into the shopping cart as you purchase signs and business cards; it’s increasingly the entire digital storefront and a critical system of record. The companies that do well in website building either own critical on-ramps like domain registration (Godaddy) or offer kick-ass functionality further up the stack, with sophisticated, friction alleviating technology and/or 3rd-party app integrations (Wix and Shopify). And there’s a reason why website builders don’t bundle business cards…not only are these offerings not a natural point of integration, but doing well in either area involves entirely different processes. I’m not rehashing Cimpress’ somewhat ignomonious capital allocation and strategy choices with snark (or I at least hope it doesn’t come across that way). On the contrary, I think it’s admirable that this management team at least attempts to take an earnest look at its shortcomings, fesses up to them, and experiments with new ideas. I bring this up just to frame the difficulty of growing through a continuous product introductions and simultaneously extracting scale economies.

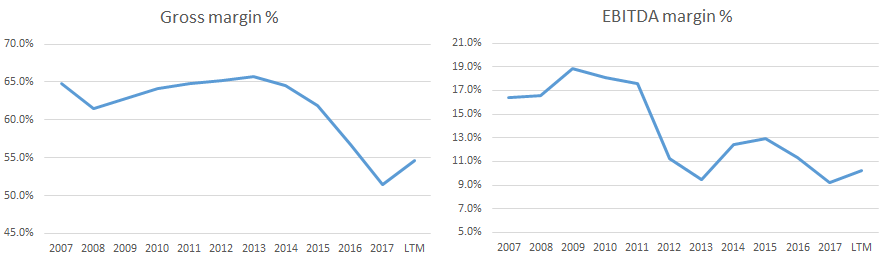

At one extreme, the company could have just stuck to business cards and closely related paper-based products, gaining a little more production leverage every year and steadily improving its gross margins…but growth would have inevitably slowed and then reversed as the market for business cards is in decline and Cimpress’ business card revenue growth has decelerated significantly over the last decade. But then, proliferating product categories to boost volume growth makes scale economies harder to come by. Through the acquisitions that now comprise its Upload and Print segment, Cimpress multiplied its SKU count by 300x, and the number continues to grow at a rapid pace. The scale benefits attending homogeneous manufacturing and fulfillment processes attenuate as you start offering different substrates and formats, and especially as you expand into banners, apparel, pens, magnets, and other trinkets made of entirely different materials, manufactured through a different process with different equipment in different countries. I think the company recognized this long ago, hence its emphasis on higher quality products to customers with better lifetime values; but I also think it’s fair to say that management underestimated how difficult it would be to reap the benefits of mass production over so many diverse product categories. Check out their margins over time…

The nosedive in gross margins can be mostly explained by investment in design services and a mix shift towards Upload and Print, which has been growing faster than Vistaprint and is more dependent on outsourced production. But, this segment also has lower sales and marketing costs per order than Vistaprint and all else equal, the two segments should have comparable EBITDA margins…but those have declined considerably as well over the last decade, even as Cimpress has shown some sales & marketing and G&A leverage over time. I think this can be at least partly explained by shipping, which runs through gross profit. The company is loath and perhaps embarrassed(?) to reveal how much money it was making on shipping, but assuming average shipping price charged to the customer of $10 and an average order value (back when management still revealed this figure) of around $35, it was clearly significant.

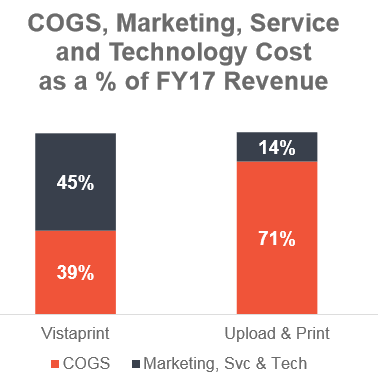

I don’t imagine its own shipping costs have changed by nearly as much, and so providing relief to its own customers likely translates to a mostly direct gross profit hit. Also, losses from the “all other business units” segment, which houses speculative investments, emerging markets, partnerships, continue to grow, from -$9mn in fy16 to -$36mn LTM. Finally, digital products and services (Webs.com I assume?) has witnessed significant revenue declines. Except for maybe losses in emerging markets, which are still small and sub-scale, none of the above mentioned causes of margin compression will reverse, so the high-teens EBITDA margins of the mid/late 2000s are likely a thing of the past. Management does not deny this and, in the face of persistently declining margins, now directs investors to think instead about dollar profits, retention rates, and lifetime customer values, tacitly acknowledging that ever more of the scale benefits are shifting from production leverage to value-add per customer. Cimpress’ last 10-K (year ending June 2017) reveals 17mn customers served by Vistaprint, which means the number of unique customers hasn’t budged since fy14. However, Vistaprint’s revenue has grown by over 25% over that time, implying that revenue per customer has gone from $65 to around $80. Management does not break out gross profit or opex by business segment in its financials, but we do have this useful exhibit from the last Investor Day:

The buyer repeat rate, at between 30%-35%, is so low that one wonders whether the lifetime value of customers is really the right metric for management to focus on, but let’s just go with it. So if revenue per Vistaprint customer is $80, then it looks like gross profit per sub is close to $50. Assuming a 10% discount rate and that 35% of buyers make repeat purchases [I’m assuming it’s higher than the 31% rate the company disclosed for fy17] implies an LTV per customer of $73. Before the company went on its acquisition spree and it was just basically Vistaprint, the cost of customer acquisition was around $24, suggesting an LTV:CAC of ~3x. Once you factor in higher recurring costs of supporting today’s relatively higher quality customers, the ratio is probably closer to 2.5x(?), right at the cusp of acceptability. To put that in perspective, Trupanion is at ~4.5x, Godaddy is over 5x. [Founder and CEO Robert Keane writes the kind of letters that value investors just eat up, chock full as they are of Buffett-esque straight talk and verbiage. But I’ve actually found disclosure to be frustratingly inconsistent. For instance, up until fy14, the company provided metrics on average order values (AOV), order volumes, repeat customers, bookings per repeat customer, and other good stuff. They stopped regularly disclosing most of this in fy15, defending the move by maintaining that a metric like $AOV doesn’t provide much insight because there are so many businesses besides Vistaprint. Like, huh? Vistaprint still represents 65% of revenue, 80% of segment profits, and the majority of organic investments. And even if that weren’t the case, why stop disclosing the very data required to estimate lifetime value at precisely the time in the company’s history when it is explicitly targeting this metric?]

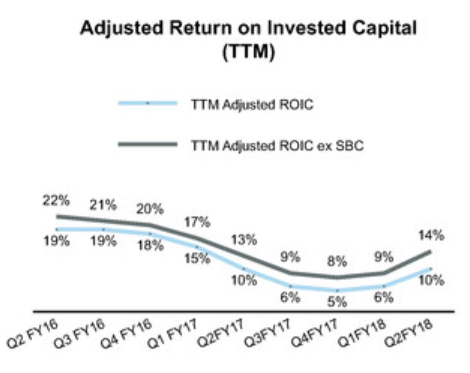

As mentioned earlier, Cimpress’ acquisitions and organic investments over the last 5-6 years appear to have impaired value, with returns on incremental capital falling short of capital costs, and over time, we see that the company’s returns have deteriorated rather markedly in even the last few years. And they are way below the the 30%+ returns the company was realizing before its spree. Meanwhile, over the last 5 years, organic growth has been cut nearly in half, from 20% in fy12 to ~10%/11% LTM.

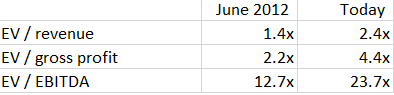

[“adjusted” because the numerator excludes restructuring charges; acquisition related earn-outs, amortization, and depreciation; and impairments] But that hasn’t stopped valuation multiples from doubling over that period.

But perhaps I am throwing excessive shade. While I think Cimpress is a worse company than it was 5-10 years ago and its mass customization platform is maybe not quite what was promised, it’s still hard to imagine a competitor rivaling Cimpress’ scale advantages, and I think the company will continue taking enough share to deliver high-single/low double-digit organic revenue growth for the foreseeable future. Founder and CEO Robert Keane, who owns 10.5% of the company and owns the same number of shares as he did 7 years ago, has significant skin in the game. The company has retired nearly 30% of its shares over the last 7.5 years in the low-$40s. Using the high-end of management’s estimate of investments required to grow free cash flow by at least inflation, LTM mFCFE per share is around $8/share [1], so the stock trades at ~20x, which doesn’t seem too demanding a valuation given the company’s competitive positioning and growth opportunities. Cimpress recently reported an outstanding quarter across all reported segments, suggesting budding traction with its decentralization initiative. But I frankly have no idea if this inflection is sustainable.

Given the pronounced deceleration in core legacy business cards, where the engine of mass customization was applied beautifully for the first 15 years of the company’s life, diversifying into far flung SKUs may have seemed sensible at the time….they were squeezing less juice from scale economies but could compensate for that by moving upmarket, offering a value-added bundle proposition with a heavier service component. But in retrospect, shareholders would probably have been better off if management just maximized the hell out of lower organic growth and plowed excess capital – capital that could not be reinvested into core Vistaprint – into share buybacks rather than acquisitions. [1] Estimating relief under the new US tax law is tricky because the company already reallocates income across a sprawl of geographies to minimize its tax payments. Cimpress derives just 40% of its revenue from the US and over the past year paid just $40mn in cash taxes on $180mn in pre-tax cash profit, so I’m not so sure the new rule will meaningfully benefit the company.