SAMPLE POSTS, [MA] Mastercard, [V] Visa

A tour through payments: part 1 (Visa and Mastercard)

I plan to spend the next month re-surveying the payments landscape, mostly updating my views on companies I’ve discussed in the past but also maybe laying some groundwork on a few new names. The next few posts will be a loosely organized jumble of thoughts. I don’t know where this is going or how it will end but I know where it should start: with the two dominant global card networks, Visa and Mastercard, which I’ve written about several times in the past and have owned on and off over the years.

Like some other companies that have held their market values this year, Visa and Mastercard are competitively entrenched cash gushers with secular tailwinds that have so far been unscathed by the macro. Cross-border volumes, which are far more profitable than domestic switching given currency translation fees and lower rebate burdens, have ricocheted back stronger than anyone expected, to about 40% above pre-COVID levels. With most of their revenue tied to payment flows, the card networks are also net beneficiaries of inflation. Over the last 3 years, Visa and Mastercard have grown EBITDA by 9% and 11%, respectively, even with Russia revenue (4% for both) reduced to 0, and I think there’s plenty of reason to think profits will continue to grow at a similar rate for the foreseeable future.

Rather than expound upon Visa and Mastercard’s moats, which are widely understood and appreciated by now, I thought it’d be more useful to discuss potential challenges. This is conviction by subtraction, seeing how much is left after chipping away the excess stone of competitive threats.

Digital Wallets

When I first began looking at Visa and Mastercard in earnest in 2016, the most salient bear case was that digital wallets would eventually disintermediate card rails. Someone like PayPal could encourage users to directly link bank accounts to their wallets, which could then be used to transact with a PayPal-accepting merchant, creating a closed transaction loop that bypassed Visa and Mastercard. And indeed, to avoid interchange fees, PayPal encouraged this behavior in its early days. Then in 2016, with customers complaining about being defaulted to ACH, PayPal agreed to present V/MA credit and debit as “clear and equal” payment instruments inside the wallet (”Customer Choice”)1. This landmark announcement preceded a flurry of integrations with digital wallet integrations all around the world.

Today every major digital wallet and bank I can think of – including Cash App, PayPal, Apple, Venmo, Grab Pay, MercadoPago, Monzo, etc. – embeds or issues Visa or Mastercard credentials. It’s easy to see why. Consumers want the assurance of knowing they can spend at just about any merchant around the world, online and offline, and earn interchange-funded rewards along the way. A digital wallet that didn’t plug into card rails would soon find themselves at a steep disadvantage to competing wallets that did.

With few exceptions, the relationship between the card networks and digital wallets is a symbiotic one. Visa and Mastercard, with their combined ~170mn merchants, enable immediate global acceptance that results in lower churn, larger order values, and more profit dollars for digital wallets. In turn, digital wallets, with their direct consumer relationships, expand distribution for card networks. Far from being a critical point of integration sweeping value away from card networks, fintechs have pulled more transaction activity onto them.

Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL)

In a BNPL-funded purchase of, say, a $1,000 sofa, the BNPL provider will pay ~$950 to the merchant and keep ~$50 for itself, then collect 4 separate $250 payments from the shopper over 4 weeks or whatever. So this is technically a loan, but as I explained in a previous post:

… the easier BNPL is to use and the more ubiquitously adopted it becomes, the more it behaves like a payments network than it does a loan (unlike traditional lenders who live on net interest income, the vast majority of BNPL revenue comes from merchant fees). The more checkout pages that support Affirm the more useful it is for consumers, and a shopper who signs up for Affirm at one merchant will start using it at other merchants too. The more transactions a BNPL facilitates, the more SKU-level and repayment data they have to underwrite risk and offer a greater variety of payment options to consumers at checkout (in contrast to credit cards, which offer blunt homogenous credit terms across all purchases), fueling conversion gains and merchant adoption.

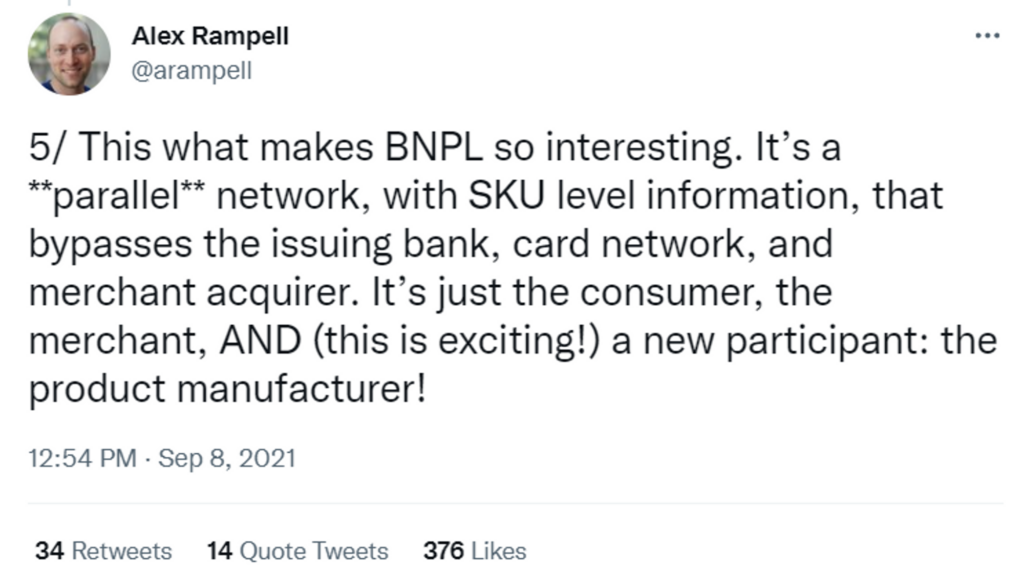

You can see how in theory the mechanics of BNPL could spool up to a competing payment network. Last year Alex Rampell, a General Partner at a16z, who set out to explain why BNPL was “an early threat to trillions of dollars of market cap – Visa (almost $500B), MasterCard ($350B), card issuing banks, acquiring banks/services (Fiserv, FIS, Global Payments, etc)?”, gushed:

But this isn’t entirely accurate. Card networks profit from BNPL in a number of ways.

First, more than 80% of BNPL installments are repaid with debit, and thanks to fixed per-transaction fees, Visa and Mastercard make more from 4 separate $250 payments than from a single $1,000 payment.

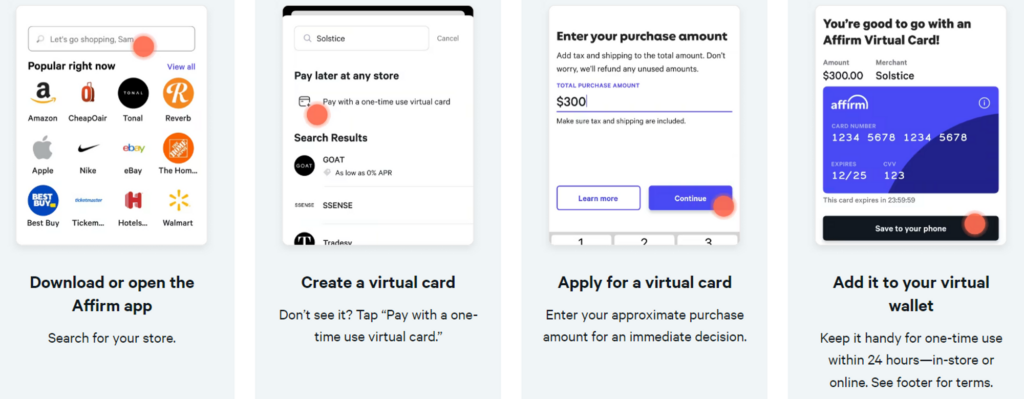

Second, BNPL providers are now using virtual cards (a single use card for a specific amount) to settle with merchants. The way this works is inside the Affirm app, a user can load a Visa virtual card for some arbitrary amount, spend that sum at any Visa-accepting merchant, and pay off the balance over time (see the illustration below):

Source: Affirm

Consistent with Visa and Mastercard’s position as a platform that other fintechs build upon, any qualifying bank and fintech can leverage Visa and Mastercard open loop BNPL capabilities. Open BNPL is early but catching on, with Visa recently reporting triple digit volume growth and Affirm’s virtual card revenue accounting for 18% of revenue, up from 12% a year ago. The reason that BNPL fintechs with putative schemes to disrupt traditional card rails are partnering with them instead is pretty simple: widespread merchant acceptance. Compared to Affirm and Klarna, who combined are embedded at checkout at ~700k merchants, Visa and Mastercard are accepted by 170mn. Rather than piecemeal integrate with merchants, fintech BNPLs can partner with Visa and Mastercard and reach immediate global scale.

Admittedly, pre-loading a virtual card isn’t as seamless a user experience as having it available at online checkout. And in the case where a consumer BNPLs with Affirm at checkout and repays with ACH, the card networks are indeed obviated. But in the increasingly common scenario where the BNPL provider settles with the merchant through virtual cards and the consumer pays off BNPL balances with debit, Visa and Mastercard make money twice on the same purchase. As with digital wallets, BNPLs may ultimately reinforce rather than disintermediate the card networks.

I’m not nearly as bearish on the concept of BNPL as many others. There’s a place for it. But I also see BNPL less as something to build a company around (AfterPay shareholders were indubitably bailed out last year when Square agreed to acquire the company for an absurd 40x revenue) than as yet another feature nestled inside the portfolio of a larger financial concern. PayPal has 35mn merchants in its network and claims it can underwrite to higher acceptance and lower loss rates by virtue of having a pre-existing relationship with 90% of its BNPL users. In less than 3 years since launch, it has become the largest player in the space. Banks, meanwhile, have an entrenched customer base and can fund loans with sticky low cost deposits. By contrast, standalone BNPLs looking to bypass Visa and Mastercard have just a fraction of the merchant base to build off. And to fund receivables, they rely on securitizations and forward flow agreements, whose availability and cost is subject to market conditions.

Crypto

For purposes of this discussion, we can segment the universe of digital assets into: cryptocurrencies with no fiat backing (Bitcoin, Ethereum), private stablecoins (Tether, USDC), Central Bank Digital Currencies (China’s e-yuan; The Bahamas’ sand dollar), and non-fungible tokens (Cryptopunks, Bored Apes). Visa and Mastercard touch all these categories. Their rails serve as “on-ramps” to purchase Bitcoin, NFTs, and other crypto assets on Coinbase and other crypto exchanges and, with practically no merchants natively accepting crypto of any kind as a form of payment, as “off-ramps” from the self-contained crypto universe to the real world. For instance, when a Coinbase customer uses their Coinbase debit card to purchase a cup of coffee, Visa will convert some of the customer’s Bitcoin (or Ethe or Dogecoin) to a government-backed fiat currency that Starbucks can actually accept. Finally, when it comes to CBDCs – digital tokens issued by a central bank – Visa and Mastercard will directly settle those just as they would any other government-backed fiat currency.

The profusion of frauds and collapsing crypto prices has deflated the crazed optimism that once characterized this space. Visa and Mastercard didn’t get the memo. They’re still talking about cryptocurrencies and NFTs like its 2021. But I doubt they care as much about crypto as the skeptics and optimists who have been emotionally hijacked by it over the years. V/MA see themselves as payments infrastructure and are philosophically agnostic to whatever form factor payments take, as they should be. You can be cynical about the whole crypto complex and still agree that Visa and Mastercard should lay the groundwork for playing a role in it. There is no contradiction here. In owning ubiquitous payment infrastructure, the card networks can absorb frontier payments technologies without bearing much risk, adjusting their investment based on how things play out. In fact, it would be worse if the card networks took the strong dogmatic view that all this crypto stuff is garbage and ignored it completely, not because crypto is the next big thing but because that reactionary attitude would likely extend to other domains of innovation that may seem dumb and insignificant at first but prove worthwhile after all.

I could see stablecoins being used for certain big ticket cross border B2B, or for remittances and as a store of value in countries plagued by hyperinflation and corrupt authoritarian regimes. For those privileged enough to be living in stable liberal democracies with strong institutions and mature banking systems, crypto can do some of what the tradfi apparatus does, but it does those things much worse. It is slower and more cumbersome. The irreversible transfer of value is a bug, not a feature, in retail transactions. In the unlikely scenario that stablecoins find broader acceptance as a directly settled currency, there will likely be a long transition period where those coins must be converted to fiat to be useful and the globally ubiquitous card networks already do something similar in converting one fiat currency to another for cross-border transactions. Moreover, as Visa likes to point out, even a popular stablecoin like USDC runs on 8 different blockchains. The card networks are well placed to integrate across them, in much the same way they function as a hub across different fiat payment rails today.

As for CBDCs, assuming the end state isn’t a Soviet-style Gosbank that crowds out commercial banks, we’re probably looking at some kind of public-private hybrid – with private banks handling KYC, lending, account maintenance, and other consumer-facing functions and central banks controlling the supply of digital money and financing commercial banks’ lending activities (consumer deposits would technically sit on the central bank’s balance sheet, not the commercial bank’s) – that from the consumer’s perspective largely resembles what we have today, in which case the current card networks probably remain intact, settling CBDCs like any other fiat. But I frankly don’t see the point of CBDCs, at least in the US. Americans trust that funds deposited at commercial banks are secure thanks to capital requirements, deposit insurance, and liquidity facilities backed by the Fed. And there just doesn’t seem to be enough friction in payments and access to banking services to warrant such a radical departure from the status quo.

Real-time payments

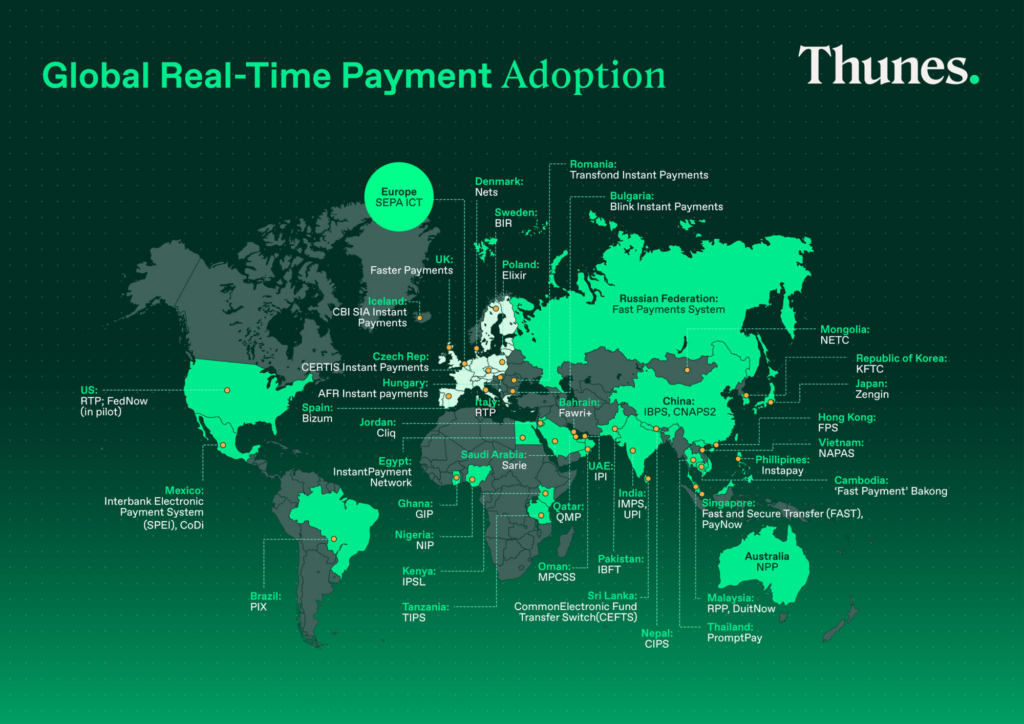

The perennial bull case for Visa and Mastercard is that their networks will capture a growing share of payment flows as electronic payments replace cash and checks. But card networks aren’t the only winners. A number of government backed real-time payment (RTP) networks, which facilitate the transfer of funds from one bank account to another in real time 24/7, has launched over the last 7 years. There are a few dozen scattered throughout the world today:

In most countries, RTPs have mostly been relegated to P2P transfers, bill payments, and B2B. But there are several notable exceptions – The Netherlands, Brazil, and India – where ease of use and commercial bank sponsorship have spurred significant person-to-merchant (P2M) use.

In the Netherlands, iDEAL is an online payment system launched by a consortium of banks in 2005 that today has more than 70% share of the country’s e-commerce transactions, though debit cards still account for 85% of point-of-sale transactions and point-of-sale still comprises more than 80% of retail purchases.

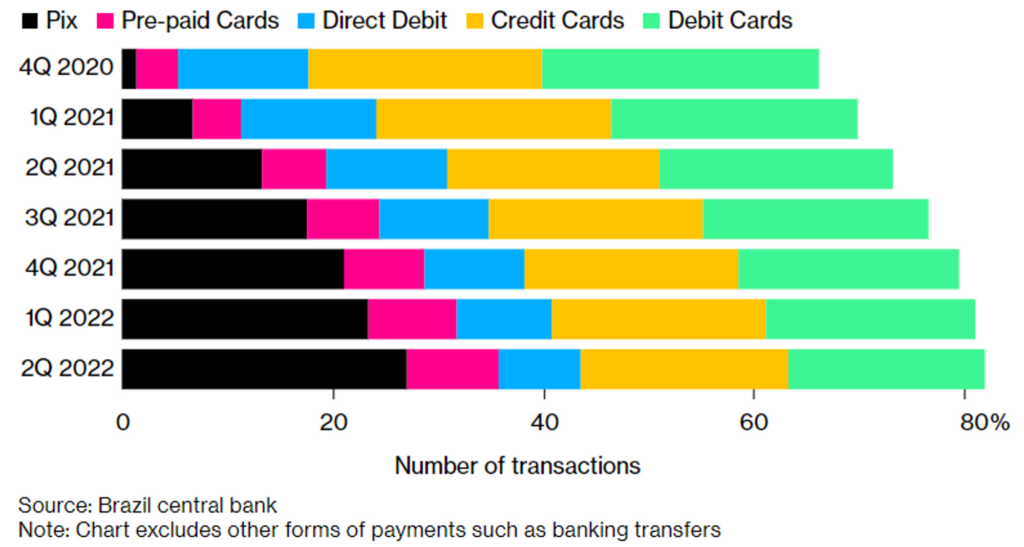

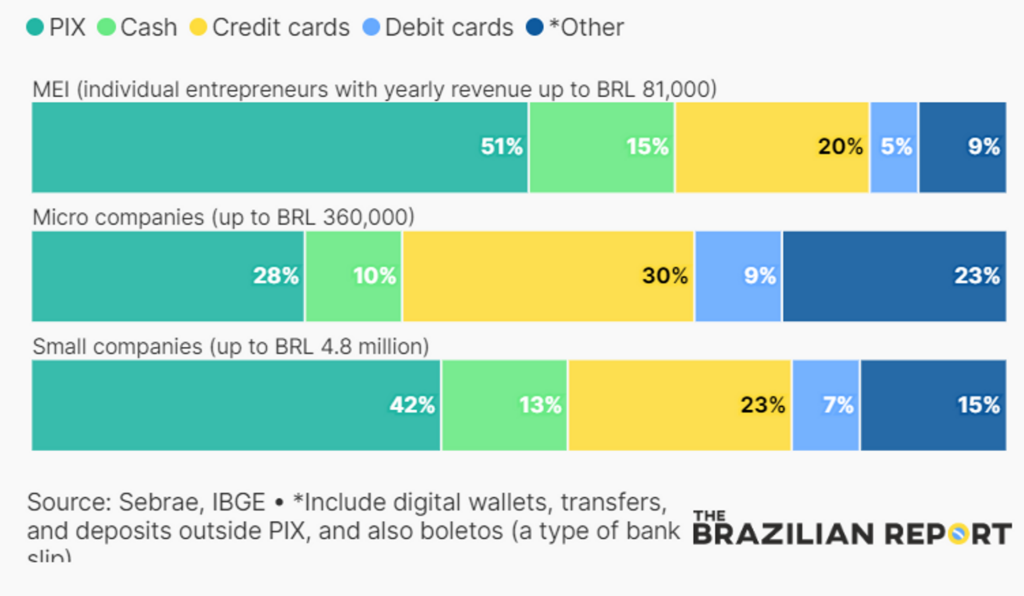

Pix, designed and managed by Brazil’s central bank, has become the most popular form of payment in Brazil, claiming ~30% of the country’s transactions in less than 2 years since launch. It has been used by more than 70% Brazilians, who need only enter a phone number, email address, or taxpayer ID from their banking app or wallet to send payments instantly.

Source: Bloomberg

With funds from credit card transactions available only after 30 days to and merchant discount rates running as high as 1% for debit and 2% for credit, Pix’s instant transfers and 0.2% fees were enthusiastically embraced by Brazilian merchants:

In India, Unified Payment Initiative (UPI), launched in 2016 by the National Payments Corp of India, a non-profit retail payments organization created by the Reserve Bank of India, has exploded in popularity. UPI is the payments layer of the India Stack, a massive government sponsored project conceived in 2009 to usher the country’s 1.2bn+ citizens into the digital economy. Over the last 3 years, with its transaction volumes have soaring by 9x, UPI has become the most common electronic payment method in India, accounting for 63% of India’s non-cash transactions2. It claims 41% share of person-to-merchant transaction value (56% by volume), on pace to overtake debit and credit, which still capture 53% of merchant acceptance by value, 26% by volume3.

In the US, the Federal Reserve is rolling out FedNow, in mid-2023. Were it to gain the same degree of P2M adoption as iDEAL, Pix, and UPI, FedNow would be very damaging for Visa and Mastercard, who derive 49% and 37% of respective purchase volumes from the US. Whether FedNow comes to claim the incremental flows that otherwise would have been intermediated by Visa Direct and Mastercard Send – schemes that “push” funds from one account to another and power P2P apps like Zelle, Venmo, and Square Cash – remains an open question. But the P2M flows that make up the vast majority of V/MA profits are probably secure. Banks and card networks are just woven too tightly into US payments fabric. FedNow won’t be the first RTP in the US. The Clearing House (TCH), a payments company owned by the largest US banks, launched an instant payments network in 2017 that, despite touching 75% of demand deposit accounts, has gotten close to 0 traction in retail. In the UK, where the card networks are similarly entrenched, Mastercard tried and failed to extend Vocalink to P2M transactions through its Pay by Bank app.

But that still leaves India and Brazil, two countries long hailed by both Visa and Mastercard as growth drivers. For at least the next 5 years, I don’t think there’s much to worry about. “There’s enough TAM to go around” is a tiring cliche but in this case it happens to be true. In Brazil, cash is used in 35% of point-of-sale transactions (compared to 11% in North America); in India, it’s more like 80%.

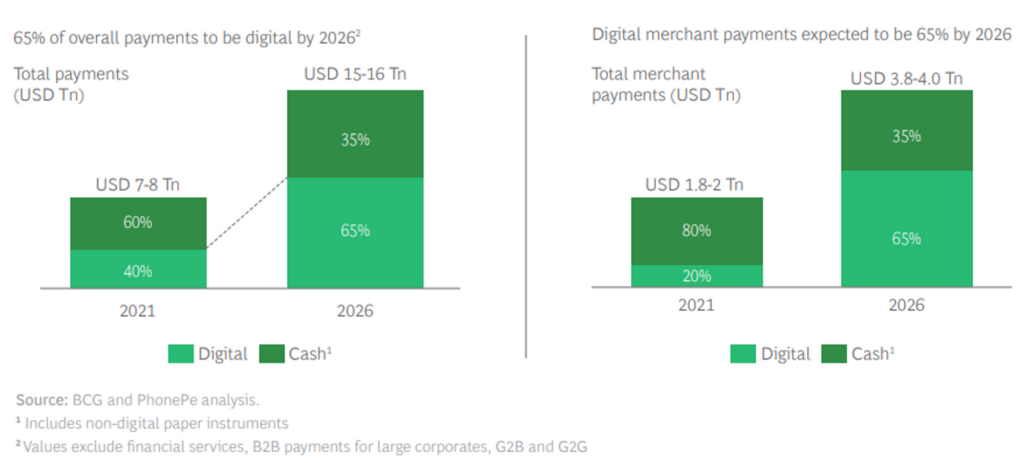

Source: Boston Consulting Group

The rising tide of cash-to-digital payments has lifted all boats. While Visa and Mastercard are less entrenched and face more direct competition in developing economies, those disadvantages have been more than offset by greater gains in per capita spending and electronic payments growth. In Brazil, Visa has doubled acceptance points over the last 2 years and doubled payment volumes over the last 3. India was Visa’s “fastest-growing market in Asia” in 2q22, with payment volumes now 84% above 2019 levels, even as UPI flows have grown at more than 3x the rate of overall digital payment volume over the last 5 years4. Since 2015, Mastercard’s transaction volumes in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East have grown by ~18%/year compared to ~8% in the US. For Visa, it’s been more like ~14% and ~8%, respectively5.

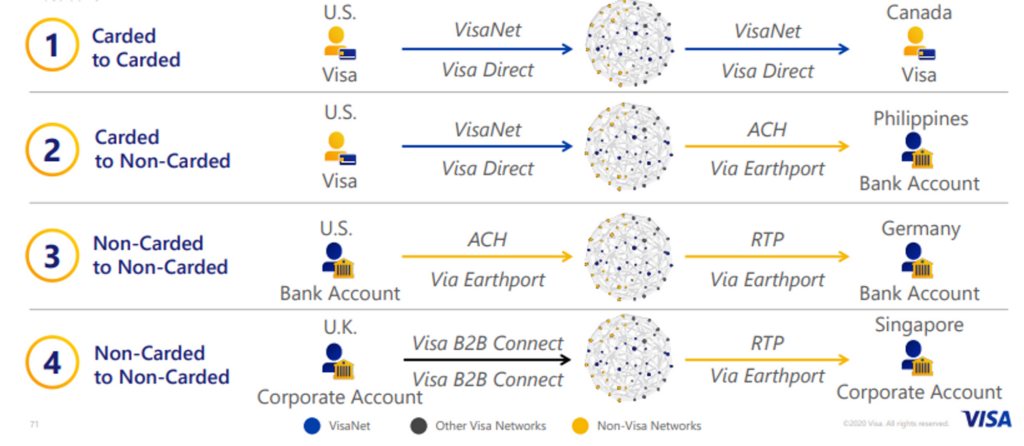

Nevertheless, Visa and Mastercard were unnerved by the long-term threat posed by alternative payment systems and around the time these RTP rails were taking off, both companies began to look beyond card rails and traditional P2M flows. In 2017, Mastercard acquired Vocalink, which runs the UK’s real time ACH infrastructure, and then used Vocalink’s software to power real time rails in Canada, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, and the US6. With the purchase of Nets, Mastercard gained access to real-time account-to-account (A2A) in Europe. With Transfast, they acquired payments web that ensnared “90% of the population and over 90% of the world’s bank accounts.” Visa also expanded its network to include cross-border A2A through their acquisition of Earthport, a payments facilitator with direct connections to the local ACHs and RTPs of 88 countries, connecting to 2bn end accounts. Through a partnership with Thunes, a payments platform that connects 78 mobile wallet operators across 44 countries, Visa Direct can reach 1.5bn individual wallets. Today Visa’s “network of networks” include 66 ACH rails and more than a dozen RTPs.

While this was going on, European regulators enforced its Payment Services Directive part Deux (PSD2), mandating that banks expose APIs that grant third party service providers access to customer bank account information (with the customer’s permission, of course). The regulation fueled open banking aggregators like Plaid and Tink that intermediate the flow of data from banks to any number of third party apps. Anticipating a time when open banking networks would also come to handle the movement of funds and challenge debit flows, Visa acquired Tink7, the largest financial data aggregator in Europe, while Mastercard purchased US-based Finicity and Denmark-HQ’ed Aiia. For now, open banking is mostly about moving data, not money. For instance, through Plaid, a personal finance app might pull transaction data and savings balances from a customer’s bank account to deliver a personalized budget or a mortgage lender might verify income and assets. Finicity offers credit scoring for bank and fintech partners who use Mastercard’s BNPL. Consumers could increasingly use open banking to pay at online checkout or to fund digital wallets, which can then be used to pay for things, cutting card networks out of the transaction loop entirely. But in both cases you’re still stuck with the problem of merchant acceptance. An new open banking checkout button from Vyne will have to compete with established buttons from PayPal, Amazon, Apple etc., and there’s a reason why just about all major digital wallet have abandoned their closed postures and opened up to the card networks.

Concurrent with their expansion into A2A, both Visa and Mastercard modified their traditional card rails to accommodate “push” transactions – so whereas in a traditional card transaction, the merchant “pulls” funds from the consumer, with Visa Direct and Mastercard Send, payments can be pushed from consumers to consumers, from Allstate to policyholders, from Uber/Lyft to drivers, from Square to merchants, from businesses to employees seeking paycheck advances.

By integrating their card networks to alternative rails, Visa and Mastercard have positioned themselves as a global payments router, replacing unwieldy bilateral connections with a single hub that spokes out to billions of bank accounts and card credentials, accommodating a wide range of different payment flows: P2B, B2B, and P2P via card-to-account, account-to-account, and card-to-card.

Source: 2020 Visa Investor Day

Whereas Visa and Mastercard span the globe, government-sponsored instant payment rails are for the most part only useful for domestic transactions. A Brazilian can’t use Pix to subscribe to Spotify or purchase a handbag in Singapore. In theory, countries could solve the cross-border problem by integrating their RTPs, but in practice this hasn’t worked out. Europe has been trying to create a pan-European payment system for more than a decade. The Monnet Project Association was shuttered less than 4 years after it was conceived in 2008 after the European Commission refused to approve the interchange rates that member banks believed were necessary to make MP commercially viable. The European Alliance of Payment Schemes (EAPS) and PayFair also folded. The European Payments Initiative (EPI), conceived in 2020, was abandoned by more than half its member banks earlier this year. Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, the vision of a cross-border multi-lateral hub – first instantiated in the central-bank backed Asian Payment Network in 2006 – has given way to bespoke bilateral integrations (Singapore’s PayNow ↔ Thailand’s PromptPay; Thailand’s PromptPay ↔ Malaysia’s DuitNow, etc.). Given how hard it’s been for even regional RTP initiatives to get off the ground, it seems farfetched to think that dozens of siloed RTPs across the world will agree to common standards, either through a series of bilateral arrangements or a common global hub.

The other way card networks are protecting themselves from competing networks is by climbing up the payments stack. “Value-added services” have long been a part of Visa and Mastercard’s offerings, but up until about 6-7 years ago they were a side show that existed as an outgrowth of the core processing business and in service to it. For example, leveraging enormous mounds of proprietary spend data, the card networks help merchants and issuers detect fraud. They also offer marketing and business intelligence services that, for instance, can show a large fast food chain how much share they’re taking in a certain market compared to peers and how much of their spend comes from foreign card holders; or, for a card issuing banks, which rewards programs are resonating with customers or how their card programs rank in terms of spend or retention relative to peers. Visa and Mastercard compete fiercely for the business of card issuers, especially that of large money centers like Bank of America and Citigroup – the incentives offered to card issuing banks have climbed dramatically as a percent of gross revenue over time – and will use VAS as a carrot to retain them or to secure new card programs in lieu of incentives.

As the #2 player trying to differentiate and gain ground on its larger rival, Mastercard has been more tech-forward and earlier to explore fintech partnerships. They also placed more emphasis on services. With nearly every Mastercard issuer adopting at least one of its services, VAS accounts for 35% of revenue today (growing 25%+), up from mid-teens in 2012. But over the last few years, with intensifying competition from competing rails, Visa too is talking a big services game8

Whereas both companies once bound services to their card rails, they now treat it as a modular component that can be carried to competing rails. For example, with Token ID, Visa is applying tokenization9, which drives higher authorization and lower fraud rates, to RTP and ACH, with TCH recently adopting this capability (you’ll recall that TCH’s RTP is powered by Vocalink, which is owned by Mastercard). Visa Advanced Authorization, once available exclusively to Visa issuers, is now being extended to merchants to detect fraud on e-commerce transactions, including transactions running on competing networks. Last year Visa rolled out a crypto consulting and analytics practice to help banks formulate crypto strategies (whatever that means). Mastercard’s rail agnostic services include ID authentication for transacting users (Digital ID, built on its $850mn acquisition of Ekata) and solutions that make it easier for consumers to pay bills and for small businesses to pay vendors, with all the reconciling data and documentation attached. Naturally they also have a crypto consulting business to help central banks design CBDCs.

So these value added products serve both an offensive and defensive purpose. They improve issuer retention and allow V/MA to extract more value from their entrenched card rails. But as payment flows extend beyond P2M, and as governments, especially those in countries whose payments industry hasn’t matured alongside a 4-party card system, roll out their own RTPs, a growing share of the ongoing cash-to-digital migration could be captured by competing domestic rails, in which scenario Visa and Mastercard can maintain relevance by supplying the technology that renders those rails more useful and secure.

Regulation and perception

Like any globally dominant American company, Visa and Mastercard are greeted with varying degrees of circumspection by foreign governments who would prefer their critical infrastructure be locally owned. In the extreme, foreign card rails are blocked from domestic switching, as in China and Russia. But even without outright banning Visa and Mastercard, governments can still exercise soft power by promoting local schemes. In India, Rupay – the local card scheme launched in 2012 by a consortium of major banks, some state owned – has captured the highest share of debit and credit cards, prompting one senior Visa official to remark:

“The only reason RuPay has added so many is not because it is cheaper, but because there is an invisible mandate from the government to issue only RuPay cards. More than half of the cards issued have not been used. NPCI can claim to issue millions of cards. But these cards are not as a result of competition, but due to a monopoly.”

And last year, Reuters reported:

…U.S. government memos show Visa raised concerns about a “level playing field” in India during an Aug. 9 meeting between U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Katherine Tai and company executives, including CEO Alfred Kelly.

“Visa remains concerned about India’s informal and formal policies that appear to favour the business of National Payments Corporation of India” (NPCI), the non-profit that runs RuPay, “over other domestic and foreign electronic payments companies,” said a USTR memo prepared for Tai ahead of the meeting.

Yet, even with 60% share of issued cards as of 2020 (up from 15% in 2017), Rupay handles less payment and transaction volume than Visa and Mastercard combined. The disparity comes from the fact that credit cards account for a disproportionate amount of spend – credit volumes exceed debit volumes despite accounting for just 10% of total cards issued – and are predominantly issued to higher income consumers, where Visa and Mastercard have 70% share compared to Rupay’s 20%. So while India is contributing less to V/MA’s payment flows than it otherwise would absent government-backed competition (UPI and Rupay), with cash giving way to electronic payments and consumer credit adopted by a growing middle class, the country is still additive to the card networks’ overall growth.

In the US, regulation hasn’t been nearly as heavy-handed, though the rationale behind it is less straightforward and arguably more disingenuous. The latest legislative proposal, Card Competition Act of 2022, introduced by Senator Dick Durbin, prohibits banks with more than $100bn of assets from restricting the processing credit card transactions to Visa and/or Mastercard’s network. This means merchants can route Visa and Mastercard credit transactions on competing rails, introducing more competition among credit card networks that will translate to lower interchange fees for merchants. The CCA builds upon the Durbin Amendment of 2011, which you may recall cut debit interchange for certain transactions from ~1.55%-1.6% + 4c/5c to 0.05% + 21c, reducing interchange fees per covered transaction by 45% on average.

Opponents of the V/MA duopoly will indignantly emphasize the huge gross dollar sums paid to banks and card networks, like: “Merchants paid $64 billion in interchange fees just to Visa and Mastercard in 2018” (The Week); “In 2021 alone, U.S. merchants and consumers paid nearly $138 billion in card fees” (Merchant Payments Coalition); and “Swipe fees big banks charge merchants to process credit and debit card transactions totaled nearly $138 billion last year. That’s 10 times North American movie theater box office receipts in pre-pandemic 2019 and 2020” (The Topeka Capital Journal). But of all the pro-merchant, anti-V/MA commentary I’ve read, I have yet to find one that mentions the obvious: that nearly all interchange fees go to preventing fraud, servicing cardholders, and subsidizing consumer rewards.

Dick Durbin thinks “credit card swipe fees inflate the prices that consumers pay for groceries and gas”, which assumes that in the absence of interchange, merchants would pass the swipe fee savings to consumers. But in a 2014 study, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond found that the 2011 Durbin Amendment capping debit interchange “has had a limited impact on prices. Averaging across all sectors, it is estimated that the majority of merchants (77.2 percent) did not change prices post-regulation, very few merchants (1.2 percent) reduced prices, while a sizable fraction of merchants (21.6 percent) increased prices”. Moreover, a 2014 study published by the Federal Reserve Board concludes “that covered banks increased their deposit fees in response to the [Durbin Amendment]. While these increases are generally insufficient to mitigate all of the lost interchange income, changes in deposit fees offset roughly 30 percent of the lost interchange income”. A 2019 study published by the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School goes even further:

we find significant evidence of banks offsetting Durbin losses by raising other account fees. The share of free basic checking accounts (accounts with a $0 monthly minimum for all customers, regardless of account balance) decreases from 60 percent to 20 percent as a result of Durbin. Equivalently, average checking account fees increase from $4.34/month to $7.44/month. Monthly minimums to avoid these fees increase by around 25 percent, and monthly fees on interest checking accounts also increase by nearly 13 percent. A rough back-of-the envelope calculation suggests that banks make up approximately all Durbin losses. These higher fees are disproportionately borne by low-income consumers whose account balances do not meet the monthly minimum required for these fees to be waived.

And despite some caveats:

we can conclusively show that consumers experience immediate Durbin losses through higher bank fees, and we find limited evidence in the gas industry for across-the-board consumer gains through significantly lower merchant prices.

Likewise, in Australia, where the Reserve Bank of Australia cut credit interchange from 0.95% to 0.55% in 2003 and slashed Visa debit interchange10 from 0.53% to 12c per transaction in 2006, the consulting firm Charles River Associates found that the “regulations have clearly harmed consumers by causing higher cardholder fees and less valuable reward programmes and by reducing the incentives of issuers of four-party cards to invest and innovate. At the same time, there is no evidence that these losses to consumers have been offset by reductions in retail prices or improvements in the quality of retailer service. The empirical evidence thus provides no support for the view that consumers have derived any net benefits from the intervention.”

It’s fair to say that interchange is a costly fee for card-accepting merchants. But cutting it appears to impose net costs on consumers in the form of higher banking fees and lower rewards. So in a two-sided card network, interchange reduction basically amounts to a zero-sum wealth transfer from consumers to merchants. Of course, you can always argue that merchants deserve more consideration than consumers but to my knowledge no anti-interchange advocates actually make this point, presumably because it doesn’t play as well as the classic cartoon representation of a mustache-twisting cabal of banks and card networks extracting value from helpless merchants and consumers.

Consider this screechy article from The Week, which declares: “There is no possible moral or economic justification for these fees. Credit card companies and their bank allies are just abusing their market power to soak the rest of society for easy fat profits” and “the immense profits of Visa, Mastercard, and the card-issuing banks are sheer parasitism”.

No possible moral or economic justification? Sheer parasitism? That’s a little intense. Thanks to the card networks, merchants realize more sales volumes than they otherwise would and consumers enjoy rewards, convenience, and global acceptance. Because of continuous investments in fraud management and the collateral requirements that card networks set for member banks, you can hand your Visa or Mastercard to any one of 170mn merchants around the world, complete a transaction within seconds, and know that if you’re ripped off you will be made whole. The merchant, without knowing anything about you, can rest assured that money from your bank will reach theirs. For enabling all this, the card networks take just ~0.2% of the transaction value. That’s not a scam; it’s a marvel.

Or here’s a letter addressed to members of Congress in which the Merchant Payments Coalition, a group of merchants “dedicated to fighting unfair credit and debit card fees” writes of Visa and Mastercard’s dominance of the US credit market:

This blocking of competition drives up prices for merchants and consumers, harms security and strangles innovation.

And in this edition of the SITAL Week newsletter (which I enjoy and recommend subscribing to), Brad Slingerlend, who quoted from that article from The Week in apparent agreement with its premise, writes:

It’s popular to raise the golden “network effect” defense of credit cards payments. I don’t completely disagree, but the stranglehold of Visa and Mastercard in the US is causing consumers and merchants, notably small businesses, to miss out on progress and innovation, as evidenced by less than 10% consumer adoption of mobile payments in the US despite their widespread use in other parts of the world.

To use the fact that Americans more often pay for things with their cards than with their phones as evidence that consumers and merchants are missing out on progress and innovation is to have a weirdly narrow definition of progress and innovation. Like you know that Visa and Mastercards are tricked out with NFC technology that allow shoppers to tap-to-pay with them in much the same way they would with smartphones? More than half of all face-to-face Visa transactions (~30% in the US, 70% everywhere else) are now contactless.

Besides, card rails aren’t even about cards anymore. Visa and Mastercard care about credentials, not physical plastic rectangles. Whether you swipe with a card or transact through a digital wallet linked to a V/MA card makes no difference to them. Americans still use cards more often than not at checkout, sure, but they do so out of habit and choice, not because grasping card networks make any other option impossible.

More generally, I find it easier to argue that card networks enable more innovation than they cripple. Much as AWS and Azure have allowed a new generation of SaaS companies to scale by eliminating the heavy upfront costs of compute infrastructure, so too have the open rails and merchant networks of Visa and Mastercard given rise to new issuers and digital wallets. The growing breadth of products from Stripe and Square are built atop payments businesses that have only scaled as a rapidly as they have thanks to the card rails. Visa powers modern card issuing platforms like Marqeta, whose APIs allow developers to customize spend preferences and manage payment programs. Even crypto exchanges like Coinbase are rendered more useful by the bridge to fiat laid out by the card networks.

As you can plainly see, I disagree with the argument that Visa and Mastercard are rapacious, innovation-stifling actors. But I understand where it’s coming from. Visa and Mastercard indeed constitute a powerful duopoly in the US. Interchange fees have an explicit and direct impact on merchant profits while the counterfactual impact on sales volumes and network security were those those fees to go away is invisible. Merchants bearing the concentrated and explicit costs of interchange are far more motivated to write letters to their Senators than consumers, who don’t even know what interchange is let alone that it funds the perks they enjoy. If your understanding of card networks is limited to news articles and click-bait editorials, you will come away with a simplistic and distorted understanding of how the payments ecosystem works, overlooking the trade-offs and compromises and flavors of coopetition that allow it to function as well as it does.

Still, perception shapes public outrage which in turn can guide regulatory interference. Sensemaking is not an antidote to misguided regulation. That the justification for CCA seems at best incomplete doesn’t preclude its passage. Durbin tried but failed to attach CCA as an Amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act this October and I don’t know where things stand today. There are various costs and complications to enforcing CCA, like re-issuing cards, re-jiggering point-of-sale software and hardware, plus what happens to a consumer’s rewards if a Visa card transaction is routed to a non-Visa network? But were it to pass into law, the Act could be more damaging to the card duopoly than the 2011 Durbin Amendment ever was. The latter regulation crushed debit interchange but didn’t cut Visa and Mastercard out of the transaction loop, nor did it have any discernible impact on their fees, which are separate from interchange. By allowing the merchant to route transactions to lowest cost networks, the CCA competes down interchange fees but also, more consequentially for V/MA, raises the possibility that payment flows will be routed to competing networks. Visa and Mastercard will naturally argue that smaller rails with fewer resources to invest in fraud management may be less secure, but even if that’s true I suspect most merchants will assume all card networks are equally safe and just go with the cheapest option.

In a battle between small merchants and a big bank/card network partnership, public officials will always side with small merchants, especially since another protected class, consumers, are too unorganized and uninformed to understand how they are being net harmed by any resulting measures. This means the threat of regulations and fines always looms in the background for Visa and Mastercard. I won’t get into it all here. Just Google “Visa and Mastercard, antitrust” or whatever and you’ll see all sorts of articles about probes and fines that have been directed at the card networks over the years. I’m not saying these punitive measures were unjustified (they may have been, depending on trade-offs you are willing to make), just that regulation is an ongoing overhang, not some one-off. But so far the card networks have thrived in spite of the scrutiny. Visa and Mastercard are like the Teflon Dons of corporate world. Nothing really sticks.

With respect to ostensible fintech threats, the card networks are more like The Blob, getting stronger as they absorb the benefits of wallet and POS innovation. When PayPal boosts checkout conversion by introducing an in-app SDK and password-free authentication, or when Apple enables iPhones to be used as point-of-sale terminals, Visa and Mastercard are indirect beneficiaries. Visa’s merchant footprint and credential count have 4x’ed over the last decade, in large part thanks to the profusion of wallets, fintech issuers, payment facilitators, and terminal form factors11. There are more direct challenges to the card rails at the infrastructure layer. But just because alternative rails exist doesn’t mean consumers will use them. Can they handle dispute resolutions and chargebacks? Do they offer 0 liability protection and dual messaging? Do they have a long, proven track record of security and reliability? RTPs will get more featureful over time but as Visa President Ryan McInerney put it, “comparing an RTP transaction in 2022 to a Visa Debit transaction in 2022, let alone a credit transaction, is kind of like comparing…a landline rotary phone to an iPhone”. And while I don’t want to tempt fate, given V/MA’s global merchant acceptance and widespread consumer adoption, taking the disjointed parochial rails too seriously is a bit like wondering “is the Albanian army going to take over the world” 😉

That doesn’t mean crypto, RTPs, or BNPLs won’t capture a growing share of the incremental electronic payments. But with digital continuing to eat away at $9tn of annual cash retail transactions across the Americas and Europe, fueled by e-commerce penetration and continuing incremental advances in payments technology that alleviate friction and expand acceptance, V/MA’s carded volumes should continue to outpace PCE growth for many years to come. Moreover, the card rails are insinuating themselves into all the newfangled modes, with on and off ramps to crypto, multi-rail networks, and open BNPL enablement. Where payment flows don’t monetize directly – as in ACH and large swaths of B2B – Visa and Mastercard are instead trying to add value further up the stack.

Disclosure: At the time this report was posted, accounts managed by Compound Insight LLC owned shares of MSFT. This may have changed at any time since.

- even in the scenario where the end user pays a merchant directly from their wallet, that wallet is often funded with debit or credit (“staged transactions”), not through bank accounts (though these staged transactions are less ideal as they cut the card networks out from the final mile of the transaction, depriving Visa and Mastercard of data that could be used to bolster their value added services products).

- Boston Consulting Group: Digital Payments in India: A $10 Trillion Opportunity.

- according to the 2021 Worldline India Annual Digital Payments Report 2021. Credit cards have 26% share by value, 8% by volume; debit cards have 23% and 14%, respectively.

- 160% per year over the past 5 years compared to “just” 50% for digital payments as a whole, according to the IMF (link).

- In this comparison, Visa’s non-US volumes include Central Europe; Mastercard’s do not.

- In the US, Vocalink supports the real time rail of The Clearing House.

- after its acquisition of Plaid was blocked by regulators.

- $6bn in Services revenue (20% of net revenue, growing 20%+).

- tokenization is a technology that converts sensitive payment data to an undecipherable and temporary string of characters (token) that can’t be used for other transactions the way stolen card credentials could.

- Mastercard didn’t introduce debit to the Australian market until late 2005, at which point it agreed to abide by the new interchange policy imposed on Visa.

- Visa and Mastercard recently launched technology that allows Android smartphones to be used as POS terminals, with payments being processed in the cloud rather than on device.