Business updates, SAMPLE POSTS

interview with @LibertyRPF

I recently did an interview with my friend @LibertyRPF, who publishes an insightful newsletter covering tech, science, investing, and various other topics. It is one of my morning staples. You can access the original interview here.

Q: Hey David! It’s been a little over a year since we last did this [see 𝕊𝕡𝕖𝕔𝕚𝕒𝕝 𝔼𝕕𝕚𝕥𝕚𝕠𝕟 #𝟙 for our first interview -Lib], I’m sure a lot has happened in the interim, but first, how are you? How are Zoe and Riley, the newest members of the ’blurb family?

Hey Liberty, the twins and I are doing great! Thanks for asking.

Q: A lot of people have joined the newsletter game in recent times. What I’m curious about is, as one of the Granddaddies of the genre, at least when it comes to the financial deep-dive sub-genre, what are you noticing when it comes to having longevity in this game?

What stuff are you finding out in year three and four that you wouldn’t have easily guessed early on? What are you doing differently now, or want to change going forward?

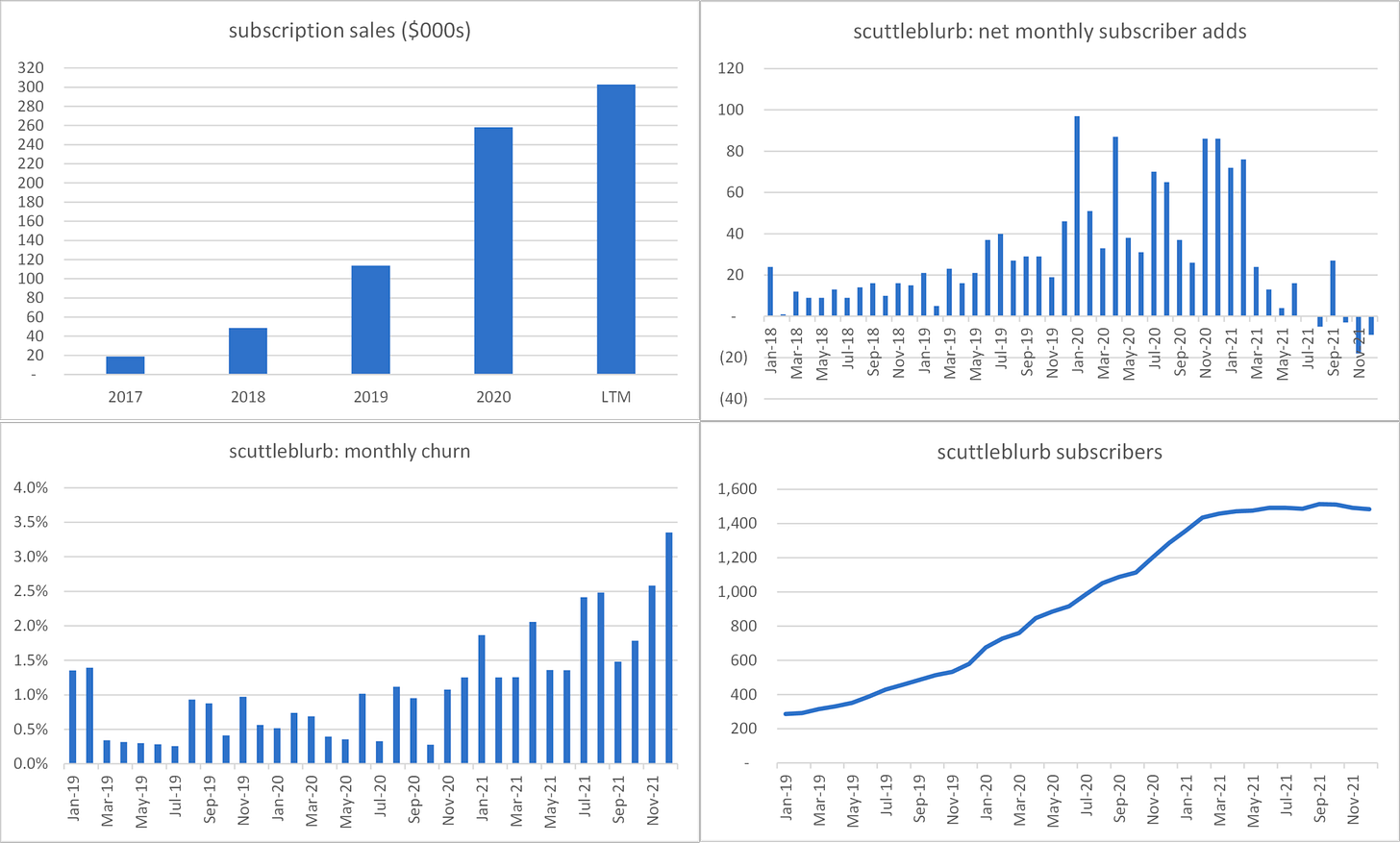

For the first few years, I was just trying to get on the radar. I didn’t know about Twitter so, like a savage, I sent personalized emails and handwritten letters with sample posts to money managers who I thought would like my work. You, @BluegrassCap, and several others tweeted my blog and pulled me into modern times. Scuttleblurb spread through word of mouth among the much-larger-than-I-imagined subset of fintwit that cares about fundamental research, which set the conditions for huge growth in 2019 and 2020. But last year, I stopped engaging and focused near-exclusively on my work. What little podcasting and Twittering I did in prior years ceased almost entirely. Reclusive behavior, combined with the explosion of competing newsletters, had a predictably stultifying effect on growth. My subscriber base flatlined for most of last year. I’m frankly surprised (and relieved) that it didn’t shrink.

I guess the super obvious takeaway here is that if you want to grow it’s important to stay top of mind through regular, substantive Tweets and podcast appearances (voice tightens the bond). Ideally, you want your newsletter to be part of a subscriber’s daily routine, something they peruse while sipping morning coffee. I know Ben Thompson’s Stratechery occupies that privileged slot for many of us. But that’s not a realistic aspiration for a deep dive writer like me who only publishes once or twice a month and doesn’t offer takes on the biggest, most topical news stories of the day.

The explosion of content has changed the way readers engage with it. Most people, including me, will flip through one essay after the next like nothing, oblivious to all the hard work and creativity that went into it. Some will cancel their subscription if they have to waste even 5 seconds logging in to read a 5,000 word post. “Too much friction”. We are spoiled with great content. I personally subscribe to over a dozen newsletters. Most sit in my inbox unread. Sometimes my auto-renewal receipts remind readers to cancel as they realize they haven’t gotten around to reading my posts. This has been happening to me with greater frequency.

“Fluff” is also friction, avoid fluff, of which there are two kinds (I’m guilty of both at times). There’s the stylistic kind where you overwhelm the reader with jargon and needless sentences. And then there’s the more insidious content-specific kind where you don’t make a meaningful point. A nice trick here is to ask yourself if any reasonable person would agree with the inverse of your claim. If not, then is your claim worth making in the first place? “We strongly believe that the best companies have durable competitive advantages, innovative cultures, and are managed by aligned founders who strive for non-zero sum outcomes”. That’s motherhood and apple pie. I have yet to come across an investor who argues for narrow moat enterprises with torpid cultures led by rapacious hired guns.

Q: There seem to be very strong forces that pull many writers out of the field. By that I mean that a successful newsletter is a great resumé, and many of the writers I know have gotten very appetizing job offers.

I feel like there’s probably only a relatively small subset of newsletter writers who truly want to write as an end goal — writing is thinking, and thinking is hard — and many others who are doing it to build towards something else. So over time they leave and it may be possible for the few that just keep on going to kind of be the last people standing through sheer longevity. I guess I’m just curious if you have any thoughts on this dynamic..?

I think you’re right – the industries where folks will pay good money for informed newsletters are also those in which writers are least committed to newslettering as a profession. Lots of folks go into finance/investing for money and prestige, and compared to managing capital or working at a hedge fund, writing a newsletter can seem like a big downgrade on both dimensions. I think this is less true than it used to be. Ben Thompson legitimized newsletter writing as a profession in so far as he showed you could earn a nice living by offering thoughtful analysis, without pumping stocks. But when I launched scuttleblurb in late 2016, more than a few well-meaning folks felt my career was moving backwards. And it’s not like my newsletter motives were “pure” either. My fund didn’t start with anywhere near the AUM to earn a sustainable living. Scuttleblurb was an attempt to generate steady income in a manner that was synergistic with managing money.

There are many more finance-interested people who want to work at or start funds than who want to write for a living….but I think those in the former camp increasingly realize the complementary value of publishing a Substack or Revue. For those trying to land an analyst job, there is no better resume than a record of your investment writing. A blog is a canvas to showcase creativity, analytical skill, passion and intellectual honesty. For emerging managers, writing is an excellent way to attract and screen for the right partners. An allocator who has read your work over the course of a year will have a clear sense of what you’re about before they reach out. It saves time on both sides.

Every so often on Twitter I’ll see someone say “if newsletter writers were any good they’d be managing money” and I always think “great, when can I expect your wire?”….as if raising capital is the easiest thing in the world. At least for me, finding aligned partners has been a long process. Getting to scale took over 5 years, it came all at once, and there are a million scenarios where I make the same moves and things don’t work out. Just because someone isn’t managing money doesn’t mean they aren’t capable of doing so. Plus, some analysts just don’t want the stress of managing outside capital. Why diminish those who take an alternative path or don’t share your life choices and goals? Isn’t it better to have thoughtful analysts out there publishing their work than not?

Q: What do you love most about this job? What part of it are you most excited about, or do you feel is most rewarding?

Definitely the money. This work feeds my family. The inspirational stuff around community, intellectual challenge, non-zero sum knowledge sharing, etc. applies of course. But this project didn’t start with high-minded aims. It started with me stressing out over how I was going to earn a living as I burned through my limited savings and struggled to launch my fund. It started with me publishing into a void and thinking I was not gonna make it. So to now have ~1,500 readers expressing support with their hard-earned cash is insanely rewarding.

Q: What do you dislike most about it? If someone told you they want to do what you do, all starry-eyed and optimistic, what warnings would you give them to make sure they know what they’re really facing out there?

There are so many newsletters competing for attention. For every successful newsletter writer, I’m sure there are hundreds more who never gained traction, not because they weren’t talented but because it’s just really hard to break through all the other terrific free and paywalled stuff out there.

If you’re thinking about starting a newsletter anyway, I would fantasize less about success and ruminate more on whether you will actually enjoy the day to day experience. Writing for a living has a certain romantic appeal, but it is a solitary endeavor that can feel like a slog for someone who does not intrinsically enjoy reading, thinking, and writing for hours on end, day after day. This job suits my personality. I crank Zeppelin and lose myself in the work. But it’s not for everyone. Some people don’t like Zeppelin. (a little dad humor for you Liberty 😉 [Ha! You know me so well! 🤓 -Lib]

Q: Last year in our interview, you wrote about your research process. I’m guessing it’s not something that changes a lot, but I’m curious if you’ve learned new tricks or changed anything since?

No, not really.

Q: Or if you’ve changed your views on anything important when it comes to your investing? Any companies or industries that you know little about, but feel like are holes in your knowledge, and you’re looking forward to digging into in 2022?

I think young fund managers, and I’ve been guilty of this too, have a tendency to over-intellectualize and complicate investing. Some of this is theater. To stand out and appear deep, one quotes Marcus Aurelius and draws facile analogies between physics and investing. By comparison, wisdom from experienced veterans can often appear trite and simplistic. But I’ve come to believe that that’s often because they’re done trying to impress. They recognize that investing is not about complex theories, superficially applied but rather basic insights, deeply absorbed. It’s that classic Charlie Munger line: “take a simple idea and take it seriously”. This is an old lesson I’m relearning. It didn’t stick the first time.

Great companies really feel this in their guts. Old Dominion Freight Lines, Sherwin-Williams (long), Fastenal, and Charles Schwab (long) are organizations that build around simple drivers of value creation. For instance, while the LTL industry embraced “asset lite” dogma, Old Dominion invested in the service centers and trucks required to offer reliable on-time service at a fair price (not the cheapest price). The profits it realized from winning share and scaling its fixed cost base were reinvested into still more service-enhancing capital investments, driving still more profitable share gains.

Twilio obsesses over developers. CEO Jeff Lawson’s 300-page manifesto testifies to this. The company is made up of Amazon-inspired multi-disciplinary “two-pizza” teams who can respond to customer needs with the agility of a startup. As they grow past 10 members, those teams split into smaller ones, with the code base divided at each mitotic [Good vocabulary! -Lib] phase so that technical debt is paid down as the company grows. All employees are required to spend time supporting customers and building software with Twilio’s APIs.

This isn’t always feel-good stakeholder capitalism stuff and there is sometimes more than one viable vector of attack. Airbnb and Booking (long) are, to borrow a phrase from William Finnegan (Barbarian Days), the “oversold thesis and understated antithesis”. Booking quietly games the mechanics of performance marketing and conversion through maniacal experimentation. They’ve systemized the process more than any other OTA, with a team dedicated to maintaining the tools and scaffolding that allow anyone in the company, including new employees – who are, by the way, trained on statistics and hypothesis formation when hired – to launch experiments without permission. To pull this off, you need a culture that runs flat and encourages frequent (but small) failures.

Airbnb is equally ambitious but crunchier. They built the most resonant brand in this space by taking community, connection, and product seriously. That Airbnb commands ~the same enterprise value as Booking on ~half the gross bookings and none of the profits is at least partly a function of vibes and storytelling: it’s easier to dream big with Airbnb than with Booking because CAC can be framed as intangible asset investment that should scale better than a recurring Google toll, and the company’s granular inventory molds better to all sorts of use cases and economic environments…though whether one is justified buying into this vision has yet to be seen. Back when Booking was at Airbnb’s 2019 level of gross bookings, it grew faster and delivered +37% EBITDA margins vs. -7% for Airbnb. Anyways, I guess the point is I tend to emphasize strategy when sometimes what really matters is that a company knows, like really knows deep in its marrow, what it’s all about and does uniquely well, top to bottom, things that are consistent with that identity.

Besides “culture”, something else folks talk about is incorporating base rates into the investment process. This sounds like good hygiene, but I find it hard to apply and even easy to misapply in practice. I once listened to a podcast interview, this was maybe 5 years ago, where the guest chided a sell-side analyst for modeling Amazon’s annual revenue growth at 15% for the 10 year period from 2015 to 2025, retorting (and I’m paraphrasing somewhat): “If you look at the top 1,000 US companies since 1950 that started with $100bn in revenue, not a single one grew 15%+ per year over the subsequent 10 years.”

I’m reminded of that classic Monte Hall game, where a prize lies in one of 3 boxes. You pick Box A. The host, who knows which box contains the prize and is tasked with opening a prize-less one, opens Box C. Do you switch from Box A to Box B? Yea, sure, because in picking Box C, the host conveys information that suggests it is more likely that the prize is in Box B. That’s just Bayesian updating. But now imagine the same setup except this time the host randomly opens Box C. Here there is no advantage to switching. In both scenarios, the observation is exactly the same: the host opens Box C; there is no prize inside. But whether you, the contestant, are better off switching hinges on whether the host knew which box held the prize and opened an empty one. To paraphrase Judea Pearl, the process by which an observation is produced is as important as the observation itself.

That “no $100bn companies since 1950 have grown revenue by 15% over a decade” may be an empirical fact, but it doesn’t take into account the process by which Amazon (long) got to where it is. The speed and intensity with which online businesses scale is unlike anything we’ve seen in the Age of Oil, Automobile, and Mass Production (h/t Carlota Perez) and it seems misguided to anchor to pre-internet statistical artifacts. It’s proper to start with the “outside” view and adjust according to local information about a company’s competitive positioning, addressable market, unit economics, etc. Too many investors get swept up in company-specific narratives and ignore broader context, that’s true. But I’ve also found that those who tsk-tsk with “no company has ever…” finger-wagging often frame against the wrong context and tend to downplay updating or don’t possess the company-specific knowledge to understand how significant that updating should be.

If you’re walking through the woods and happen across a lizard reciting the alphabet and your friend asks whether it can vocalize words, you don’t reply “the base rates don’t look good; no reptile in existence has ever uttered words”. No, first you wonder about the mushrooms you picked earlier, but then you say “holy shit, this lizard knows its ABC’s!” Not a great analogy, but you get my drift. [🦎 -Lib] That Amazon, like no other private enterprise, got to $100bn of revenue in 20 short years and was still growing close to 30%/year off that huge base is an indication that there may be something special going on here, that perhaps the idiosyncratic merits of this situation demand major updating of base rate priors. The same could also have been said of Google, also a member of the ~$100bn club, growing 20%+. Rather than cling too firmly to historical base rates, it seems more useful to ask what’s different about Amazon and Google, and to then consider the consequences of that answer. Statistics aren’t explanations. Data doesn’t speak for itself. Without a qualitative understanding of how a company creates and captures value, you don’t know why the numbers are what they are or what might cause them to break down or inflect.

Q: I know it’s hard to judge one’s own work, but I’m curious if — looking back on Scuttleblurb since the very beginning — you could share what you think were some of the high-points and low-points when it comes to your analysis. Any standouts where you think, “this really aged well, I got it right there” or “oops, I think I screwed up there for reason XYZ”..?

Like 2 or 3 years ago I wrote a few posts about how private permissioned blockchains might have some interesting business use cases… for instance, in simplifying the process of transferring land titles, counting proxy votes, and recording share ownership, tasks that are today are processed through byzantine methods subject to uncertainty, delays, and costly errors. I saw blockchain as being more about efficiency than revolution, a way to handle pedestrian record keeping tasks more transparently, at lower cost and greater accuracy. I acknowledged that there were major institutional barriers to adoption, but nevertheless thought we would be talking more about corporate blockchain today.

But enthusiasm around this stuff has waned. Today crypto ideas are more philosophical, more self-referential, less obviously and immediately useful. Remember when, to sound smart, people used to say “I’m skeptical of crypto but blockchain is interesting”? They don’t say that anymore. The party around crypto assets has drowned out staid corporate conversations around blockchain as a record keeping technology. The talk these days is more around leveraging crypto incentives to organize people for…blah…whatever, yacht parties, climate change. I pine for the days of Long Island Iced Tea Blockchain. It’s not clear to me if it is decentralization or the hype around decentralization that is doing the heavy lifting here or if it even matters. I offer no opinion on how much of this is good or bad, and have less than zero desire to defend any side of this holy war. I only mean to say that things have played out much differently than I thought they would…but of coursethey did.

I was much too enthusiastic about Twitter (long) and overestimated the pace and impact of some of their product initiatives. At first, it was almost endearing to see Twitter stand and fall (“c’mon Twitter buddy, you can do it!”) while Facebook won its nth Gold medal. But after so many years of missteps, now we’re all worried about degenerative bone disease. They’ll likely miss DAU guidance. Expenses are off kilter. Creator products were slow to launch and remain janky. Investor sentiment is terrible. Twitter’s enterprise value is about where it was in 2018/2019.

But – and here’s the part where I get booed offstage – the company is in a much better place today than it was back then. They are experimenting with new products and acting with way more urgency than they have in prior years. They’ve made it easier to onboard, proposing to users a growing selection of Topics rather than requiring them to build interest graphs by piecemeal following individual accounts. Recent and pending product launches – Spaces, Private Spaces, Revue, Super Follows, tipping, etc. – have the potential to better engage and retain users.

It’s hard to exaggerate how bad things were on the ad side. Twitter was an interest-based graph that didn’t track your interests. It would show ads based on who you followed and the ads you engaged with in the past. Hobbled by a dilapidated tech stack, Twitter would take months to roll out new ad units. But having just devoted the last 2-3 years splitting its ad server functions into separate sandboxes, the company is now developing and launching new ad formats at an accelerated pace.

Twitter won’t ever rival the “always-on” direct response dominance of Facebook – they have relatively limited data and the text-centric nature of its platform may not lend itself as well to certain visual categories. And compared to Facebook, Twitter doesn’t have near the expertise to deftly maneuver around ATT constraints. But it can certainly be a much stronger complement than it is today. The idea is that with user-side initiatives like Topics and Communities producing sharper signals, Twitter will bring a more targeted ad product to the episodic brand advertising – creating buzz around products launches, drafting off cultural moments – for which it is uniquely well-suited, as well as crystalize durable interest clusters for the long tail of smaller advertisers to DR-advertise against.

In short, Twitter is tying users to interests, which generates more targeted data for advertisers, who now also have access to a more user-friendly back-end from which to launch better converting ad formats. This is one of the most socially consequential information networks on the planet and the business is improving off a very low performance base. But man, enough already, right? This year, Twitter needs to demonstrate that its simultaneous user and ad-side efforts are bearing fruit. C’mon Twitter buddy, you can do it!

In my Zillow post, I took for granted the basic operational and blocking/tackling aspects of iBuying. When looking at the world through a strategy prism, you can sometimes lose sight of obvious ground level realities. I thought Zillow’s brand and traffic gave it an advantage in acquiring and turning over inventory, and that it could monetize rejected iOffers as highly qualified seller leads. But obviously, none of that matters if you’re recklessly buying market share at any cost and betting on home price appreciation to bail you out!

It’s not clear to me that iBuying is an inherently broken model. Opendoor seems to be doing fine, reporting strong unit margins even as they continue to expand the buy box. Zillow discarded underwriting discipline in a rush to grow. It may even be that Zillow’s existing assets and revenue streams – brand, mortgages, escrow, title, agent network – were in fact liabilities in so far as iBuying conflicted with agent lead gen or the company thought it could be a bit sloppy on iBuying because they could make up for it in other ways. Opendoor, on the other hand, had to be much more assiduous about forecasting home prices, monitoring repair costs, and otherwise managing risk because there was nothing else to fall back on. Getting the basics wrong would have had world-ending consequences for them.

But if iBuying is a viable model – “if”, because this model hasn’t been tested by a bear market and it’s unclear how much extra rake can be pushed through or how many ancillary services can be cross-sold to offset negative HPA – well, that puts Zillow in a tough spot since one of the reasons they got into iBuying in the first place was because they saw it as an existential threat to their core lead gen business. For that reason, and given Rich Barton’s propensity for shaking things up, I suspect there’s probably another BHAG in the hopper, maybe on the institutional side of things. Zillow has this amazing top-of-funnel asset that you’d think they’d be able to monetize in a big way, though I guess people have been saying that about TripAdvisor (and Twitter!) forever too.

Anyway, I could go on and on. Every one of my posts has these kinds of blind spots and shortcomings. But on the whole, I’m happy with my work.

Q: Normally I’d ask you about how Scuttleburb has been doing in the past year as a business, but you’ve published a business update at the end of December, so I’m just going to link it here:

First, while I detect a melancholy tone, I gotta say that I find what you’ve built with only your words extremely impressive, with revenue going up 15x since 2017 (and in this business, revenue and profits are fairly close if you’re a one-person-orchestra).

It’s interesting how the psychology of momentum works, and how our brains tend to extrapolate whatever has been happening recently forward. If your subscriber graph had been going up in a straight line from 2017 to 2021, it would probably feel really good. But because it’s been plateauing lately, it doesn’t feel nearly as good (even if the next phase eventually turns out to be more growth — time will tell). I think it’s important to zoom out. You’re a guy sitting at home in pyjamas, typing stuff into the computer, and you’ve materialized through sheer persistence and intelligence a community of customers that would fill a decent-sized concert hall. Kudos!

I guess this isn’t really a question, but I am curious what you think about the ups & downs of being a solo creator, and how the psychology of it plays out.

Thanks for that. I didn’t mean for the letter to come across as melancholy or pessimistic. When I say “subscriber trends look weak” and that I’m “fading somewhat amid the scrum of new talent”, well, those are just the plain realities. Acknowledging the realities doesn’t imply that I am sad or frustrated by them or hope for something better. If my subscriber count stayed flat from here on out, that would be a fantastic outcome. I just don’t want to shrink to unsustainable levels. In 2020, my annual churn was 14%; in 2021, it jumped to 26%. I think I’m still in the safe zone, but the trend isn’t great and I can’t be having like more than half my subscribers leave every year. At some point I’ll have cycled through the addressable fintwit TAM. But beyond the income threshold required to sustain my modest lifestyle, send the girls to college, and save for retirement, I don’t really care about growth. I care a great deal about doing quality work though. I think it was Ira Glass who said that at some point you get good enough at your craft to know what great looks like and it can be disappointing not to live up to that standard. I feel that sometimes.

Q: Were any of your posts from the past year particularly difficult to research, or that you learned a lot from..? Maybe things that unexpectedly went pear-shaped, like Everbridge, and how you analyzed and scuttlebutted the situation to figure out the odds on what was going on?

Hm, I don’t really have pivotal moments where everything locks into place. For me, synthesis is a gradual process. TV shows and movies emphasize silver bullet events – Bobby Axelrod lays down a big hero bet after finagling a key piece of information.

Reality is far less exciting. What really happens is you build muscle memory about a company and its ecosystem over years and calibrate conviction along the way. That’s why I would caution against buying after a first deep dive. Research should be exploratory, not confirmatory. The idea is you don’t know if the stock you’re researching is as good as you think it is at the start, but it’s very easy to convince yourself that it is just because you’ve devoted so many of your waking hours to it this month. There is a Dunning-Kruger effect at play where because you don’t know how little you know, you deceive yourself into thinking you understand more than you do….until the stock sells off by 30%. Then your hands turn to paper.

Q: Anything else you’d like to share? What did I forget to ask about?

No, except that nothing I’ve said in this interview is investment advice and I can buy or sell any of the securities mentioned at any time. Thanks for the thoughtful questions!

Q but not a Q: Thanks man!