Podcast Blurbs

Blurbs [Independence v. Diversity, S-Curves, Freedom from vs. freedom to]

Capital Allocators with Ted Seides, Ep. #32 (Paul Johnson and Paul Sonkin – The Perfect Investment)

“Fama says that an efficient stock is one where the market incorporates all available information. So, there are 3 major parts of that: the information has to be properly disseminated and the second is that it has to be processed without any systematic bias, and then the third is that it has to be incorporated into the stock price. [Processed without systematic bias] depends on the diversity of the shareholder base and then the independence of the shareholder base. So, if either of those two break down, then you have a systematic bias. And that’s two of the three areas where behavioral bias really enters into the equation. And then it has to be expressed in the stock price. And things that could prevent it from getting to the stock price, it could be that people are unwilling or unable to trade. So in terms of unwilling, it’s when you get a case like 2009 where people are afraid to put capital to work. They know it’s cheap but they are afraid of putting capital at risk. Or they’re unable to trade. And that could be because the stock is a market cap and it’s too illiquid, so if you don’t have a sufficient number of people that can express their opinions, you end up with a mispriced stock price.

On the [Processing piece], lack of diversity is when everyone’s thinking the same way – that’s a bubble or a panic. Independence is something different, where people are diverse but when they go to express their opinion, then they’re collectively influenced by some external…so, a good example would be Herbalife stock, when Bill Ackman did his presentation. You might have had diversity in the shareholder base in that people had a lot of different estimates in terms of what it was worth and then what they did was they set aside their estimate and adopted Ackman’s view and sold the stock. So, that’s really the lack of independence where they adopt someone else’s view. Diversity is kind of different because that’s when everyone is thinking the same way independently. So, one example we’ve been toying around with is imagine if you asked 1,000 portfolio managers what Amazon was worth. You might get a number like $600. Now, if you said to them, are you willing to put money on that – buy the stock or short the stock – there are a lot of people that aren’t willing to short the stock because of the risk, so the only people in the market are the ones that think it’s worth north of $1,000. So, you don’t really have diversity in the shareholder base because there’s a whole segment that’s not participating…

Just because a stock lacks diversity or independence, that doesn’t mean the price is wrong. So, we’re not saying that Amazon is mispriced, we’re just saying that the crowd is not very diverse. So, if an event happens that challenges the crowd’s view, this stock’s going to move hard and violently and we see that with growth stocks over time, if the growth breaks, there’s nobody there on the other side balancing it. You don’t have a diverse group. All of a sudden, everyone that owns it owns it for the growth, growth is no longer there. They exit. The next trade has to be somebody who sees value but at a much lower price.

10 Year Futures (vs. What’s Happening Now)

Benedict Evans:

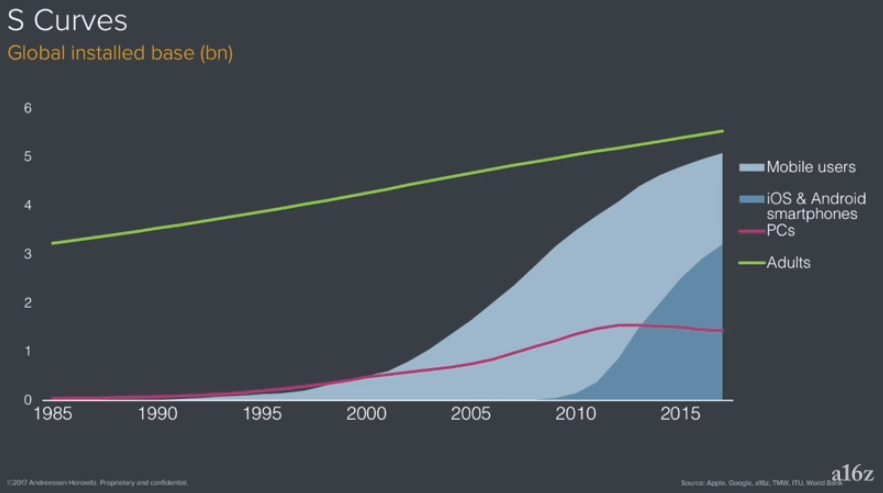

“What you see with each of these curves is that they start slowly and then they reach a point when they explode and then they kind of slow down again and get a bit boring…as we get to the stable and mature part of each of these curves, we start talking about what we can build on top of them. So, talking about mobile now feels like talking about mobile in 2004, 2005, 2006. On PCs, we talked about search and social, on smartphones, we talk about ride sharing, Instagram, Instacart and deliveries. We talk about what we can build on the platform rather than the platform itself…

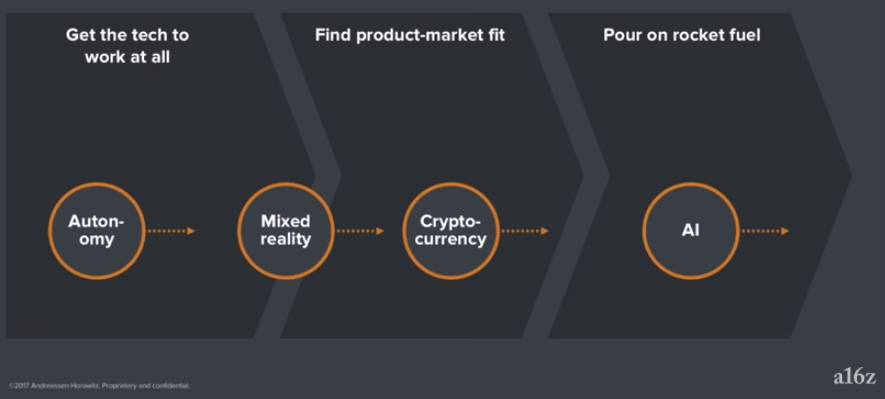

You kind of have three phases at the beginning of the S-Curve. You have the period where the tech doesn’t quite work at all but you think it will, then you’ve got the period where you’ve got it sort of working but you don’t have product-market fit, and then there’s the point when it explodes and you’re pouring on rocket fuel. So, we have 4 S-Curves today that are at various stages of that process…

AI: when I talk about enabling layers, I think a great analogy here is relational databases. Relational databases emerge in the late ’70s and early ‘80s, and they allow you to say ‘show me all customers in this zip code’ for the first time. Before that if you wanted to ask a question like that that was an engineering project and somebody would have to go spend a couple of weeks building it. Databases were not built with that kind of structure in mind.

And the fact that relational databases meant you could ask those questions meant that databases went from being record keeping systems to just replace paper filing cabinets to being business intelligence systems, and that enable all sorts of things. Most of all, of course, it enabled billion-dollar companies. So, we got Oracle. Then, we got SAP and SAP is not just a database, it’s an ERP system and SAP means that you could move your supply chain to China. And so, SAP changes what companies are and how you can run a company. And then by the 1990s, pretty much every enterprise software company is a relational database, but nobody looks at CRM or Success Factors and says ‘well, that won’t work because Oracle has all the database’. Rather, what happened is it’s an enabling layer that enables new things but enables them in all sorts of new companies…

That is the best way to think about machine learning…so, you can take a dataset and machine learning will let you find patterns. And those patterns could be all sorts of things. They can be cats and dogs, they can be different delivery routes, they can be fraudulent behavior on the network.

Finding patterns becomes a generalizable solution. So, ‘is there a cat in this picture’ becomes the same kind of question as ‘which customers are going to churn’ or ‘is that car going to let me merge’…that’s to say, you find lots of different questions and you also find things in the data that you didn’t know were there, the unknown unknowns…

When you start looking at a new enabling technology, the first demos that you see and the first things that are built with it are just expressing the capability but they’re not everything that you’re going to do with it…and so the same thing with machine learning now…what is it conceptually that we can automate with machine learning?…so, you have this pile of data where you know there’s patterns but you can’t sort it with a computer and you don’t have 100k interns to go through that data. Well, now you do. This is what automation always does, it gives you a massive multiplier effect. A steam engine doesn’t replace one horse, it gives you 1,000 horses. Machine learning doesn’t replace one person, it gives you the capability to do what you could have only done if you had 1,000 of those people before.

Cyptos: there’s sort of two ways to be at the beginning of the S-Curve. The first of those is that the technology doesn’t quite work yet, it’s not quite a product yet. And that’s where autonomy is now, it’s also where mixed reality is now, it’s also where smartphones were in 2006. The other way…is that the technology works, but we’re not quite sure what we should do with it. And that’s where HTML and the web were in 1994, it all worked fine…but it wasn’t quite clear what you could do with it and how useful it would be and what it would mean if everyone on earth was using it. And that’s pretty much where cryptocurrencies are today…

What is it that crypto automates? Well, it automates…trust. And so if you think about the process of this, money has been in the cloud in some way for centuries. So, we moved gold into banks and banks in the 18th century were basically the cloud except they had no backup, and then we moved the gold onto paper and we moved the records into punchcards and into mainframes and into databases. We changed it into a record but then we didn’t do anything with the record.

And so as we look at cryptocurrency, we start thinking about two parts of this. One of them is a distributed part, you have a database where you can put things without needing a central authority. But the other thing is that database can do stuff and the records in that database can do things and mean things that were not really possible with any previous way of storing this information.”

The Knowledge Project (2/27/17; Naval Ravikant on Reading, Happiness, Systems for Decision Making, Habits, Radical Honesty)

“I would say that the biggest such change was when I was younger, I really, really valued freedom. Freedom was one of my core, core values. Ironically, it still is. It’s probably one of my top three values, but it’s a different definition of freedom. My old definition was freedom to, freedom to do anything I want. Freedom to do whatever I feel like, whenever I feel like. Now I would say that the freedom that I’m looking for is internal freedom. It’s freedom from. It’s freedom from reaction. It’s freedom from feeling angry. It’s freedom from being sad. It’s freedom from being forced to do things. I’m looking for freedom from internally and externally, whereas before I was looking for freedom to […]

Another example of a foundational value is I don’t believe in any short-term thinking or dealing. Let’s say I’m doing business with somebody and they think in a short-term manner with somebody else, then I don’t want to do business with that person anymore. I think all the benefits in life come from compound interest, whether in money or in relationships or love or health or activities or habits. I only want to be around people that I know I’m going to be around with for the rest of my life. I only want to work on things that I know have long-term payout.

Another one is I only believe in peer relationships. I don’t believe in hierarchical relationships. I don’t want to be above anybody and I don’t want to be below anybody. If I can’t treat someone like a peer and if they can’t treat me like peer, then I just don’t want to interact with that human […]

All the real score cards are internal. The sad thing is we sit there, like jealousy. Jealousy was a very hard emotion for me to overcome. When I was young, I had a lot of jealousy in me. By and by, I learned to get rid of it. It still crops up every now and then. It’s such a poisonous emotion because, at the end of the day, you’re no better off, you’re unhappier, and the person you’re jealous of is still successful or good-looking or whatever they are. The real breakthrough for me, was when I realized, at a personal, fundamental level, the problem with these kinds of podcasts is I can give glib answers all day long, but you have to discover your own personal answer. Your personal answer is going to be different than mine. It’ll speak to you.

The one that I discovered that spoke to me was the day I realized that all these people that I was jealous of, I couldn’t just cherry-pick and choose little aspects of their life. I couldn’t say I want his body, I want her money, I want his personality. You have to be that person. Do you want to actually be that person with all of their reactions, their desires, their family, their happiness level, their outlook on life, their self-image? If you’re not willing to do a wholesale, 24/7, 100% swap with who that person is, then there is no point in being jealous.”