SAMPLE POSTS, [NVDA] Nvidia

Nvidia (NVDA): Part 1 of 2

At a high level, a computer runs a program by compiling human decipherable instructions into machine readable sequences of commands (threads) that are carried out by processing units (cores) on a CPU. So when you open a web browser, one thread might tell a processor to display images, another to download a file. The speed with which those commands are carried out (instructions per second) is a function of clock cycle (the amount of time that lapses between 2 electronic pulses in a CPU; a 4GHz processor has 4bn clock cycles per second) and the number of instructions executed per clock cycle. You can boost performance by improving clock speed, but doing so puts more voltage on the transistors, which increases the power demands exponentially (power consumption rises faster than clock speed).

So then you might try running several tasks at the same time. Rather than execute the first thread through to completion, a core, while waiting for the resources needed to execute the next task in that thread, will work on the second thread and vice versa, switching back and forth so rapidly that it appears to be executing both threads simultaneously. Through this hyper-threading process, one physical CPU core acts like two “logical cores” handling different threads. To parallelize things further, you can add more cores. A dual core processor can execute twice as many instructions at the same time as a single core; a quad core processor, 4x. Four hyper-threaded cores can execute 8 threads concurrently. But this too has it limits, as adding cores requires more cache memory and entails a non-linear draw on power. Plus you’ll be spreading a fixed number of transistors over more cores, which degrades the performance of workloads that don’t require lots of parallelism.

But use cases geared to parallel processing – those with operations that are independent of each other – are better handled by Graphical Processor Unit (GPU). Unlike CPUs, general purpose processors that execute instructions sequentially, GPUs are specialized processors that do so in parallel. CPUs are latency-oriented, meaning they minimize the time required to complete a unit of work, namely through large cores with high clock speeds. GPUs, by contrast, are throughput-oriented, meaning they maximize work per unit of time, through thousands of smaller cores, each with slower clock speed than a bigger CPU core, processing lots of instructions at once across most of the die’s surface area1.

The parallel operations of linear algebra are especially useful for rendering 3D graphics in gaming programs. To create 3D objects in a scene, millions of little polygons are stitched together in a mesh. The polygons’ vertices’ coordinates are transformed through matrix multiplication to move, shrink, enlarge, or rotate the object and are accompanied by values representing color, shading, texture, translucency, etc. that update as those shapes move or rotate. The math behind these processes is so computationally intense that before Nvidia’s GeForce 3 GPU was introduced in 2001, it could only be performed offline on server farms.

Until recently, a game’s 3D object models were smooshed down to 2D pixels and, in a process called rasterization, the shading in each of those pixels was graduated according to how light moved around in a scene2. Rasterization is being replaced by a more advanced and math heavy technique called ray tracing – first featured in the GeForce RTX series based on Nvidia’s Turing architecture 4 years ago and now being adopted by the entire gaming industry – where algorithms dynamically simulate the path of a light ray from the camera to the objects it hits to accurately represent reflections and shadows, giving rise to stunningly realistic computer-generated images, like this:

Source: Nvidia

For most of its history, Nvidia was known as gaming graphics company. From 1999, when Nvidia launched its first GPU, to around 2005, most of Nvidia’s revenue came from GPUs sold under the GeForce brand, valued by gamers seeking better visuals and greater speed. To a lesser degree, Nvidia sold GPUs into professional workstations, used by OEMs to design vehicles and planes and by film studios to create animations3. It also had smaller business units that sold GPUs into game consoles (Nvidia’s GPU was in the first Xbox) and consumer devices, and that supplied PC chipsets to OEMs.

Nvidia’s now defunct chipset business is worth spending some time on as it provides context for the company’s non-gaming consumer efforts.

In the early 2000s, Nvidia entered into cross-licensing agreements with Intel and AMD to develop chipsets (systems that transfers data from the CPU to a graphics chip, a networking chip, memory controllers, and other supporting components)4. As part of these agreements, Nvidia – which was mostly known as a vendor of standalone discrete/dedicated graphics (that is, a standalone GPU or a GPU embedded in a graphics cards) for high-end PCs and laptops, a market it split ~50/50 with ATI – supplied graphics and media processors to chipsets anchored by Intel and AMD CPUs, creating integrated graphics processors (IGPs) for the low-end of the PC market5. Nvidia could do this without cannibalizing GeForce because while integrated graphics were improving with every release cycle, they still could not come anywhere close to rivaling the performance of discrete GPUs. This was true in 2010, when Nvidia declared that 40% of the top game titles were “unplayable” (< 30 frames per second) on Intel’s Sandy Bridge integrated CPU/GPU architecture, and it remains true today.

Integrated graphics chips, while okay for flash and 2D gaming, couldn’t handle streaming media, HD video, 3D gaming, and other graphics rich functions that consumers were itching for. Operating systems from Apple and Microsoft and applications from Autodesk and Adobe were leaning more heavily on GPUs to render 3D effects. GPUs were becoming programmable (more on this later), giving rise to co-processing (aka, heterogeneous compute) – using a GPU for computationally heavy workloads while leaning on a CPU to run the operating system and traditional PC apps. In the mid-2000s, Nvidia still saw chipsets as the key to infiltrating mainstream PCs. And at least for a few years, they were right, with chipset (MCP – Media and Communications Processing) revenue growing from $352mn in fy06 (ending January 2006) to $872mn in fy09.

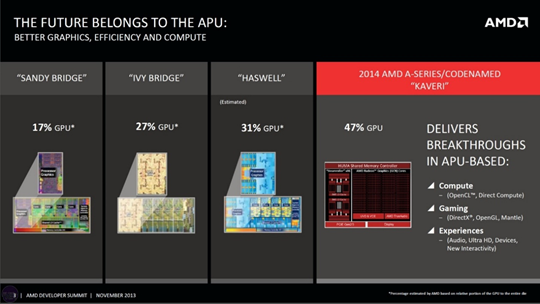

Still, in the background loomed a gnawing fear that AMD and Intel would want to own graphics for themselves. And sure enough, in 2006 AMD bought ATI6, Nvidia’s main competitor, and launched Fusion, an accelerated processing unit (APU) that put an x86 CPU and a GPU on the same chip, eliminating the data transfer and power inefficiencies of chipsets (which merely place the GPU and CPU on the same motherboard). Over time these hybrid chips, used in PCs for HD playback, videoconferencing, photo tagging, and multi-tasking across productivity apps, would achieve performance breakthroughs by dedicating ever more silicon real estate to GPUs.

Right around the time Nvidia’s AMD revenue was going away, chipset orders from Intel, which had struck a cross-licensing agreement with Nvidia in 20047 were ramping up, fueling growth in the MCP segment for several more years.

But then things got nasty. In 2009 Intel sued Nvidia, alleging that Nvidia’s ION chipset included Intel’s Nehalem family of chips, which integrated the memory controller and the CPU on a single die, a design architecture that Intel claimed wasn’t covered under the licensing agreement. And since it was likely that future CPUs would embed memory controllers, Intel was effectively terminating its agreement with Nvidia. Nvidia sued back. The Intel/Nvidia dispute was settled in 2011 with the two companies striking a new cross-licensing agreement8.

Nvidia’s MCP business was effectively dead9 but the vision of heterogeneous computing was still very much alive. Nvidia began building its own co-processors, leveraging ARM’s IP for CPUs to build low power system-on-chips (ARM-based CPU, GPU, and memory controller on a single chip)10 under the Tegra brand. Because Windows, which had a near monopoly on PC operating systems, ran on x86, Tegra chipsets were effectively locked out of PC market. But that was fine since mobile computing ran on ARM IP and at the time management was dead set sure that smartphones and tablets were going to be the company’s next big growth drivers. Nvidia imagined a bifurcated market, with high-end specialty PCs requiring its dedicated GPUs and the low-end notebooks disrupted by tablets and smartphones that would run on its Tegra chips.

In its aggressive pursuit of mobile, Nvidia found itself in competition with Qualcomm and Texas Instruments, who were starting to integrate modems with application processors. Management maintained that fusing connectivity and application processing provided no performance benefits or differentiation…but then it went and bought a modem company, Icera, in 2011. At first Nvidia insisted that the acquisition was about cross-selling rather than chip integration, but then said they were developing an integrated product to bust open the market for low-end smartphones…whatever, doesn’t matter. Nvidia was going after mobile design wins at Motorola, HTC, Fujitsu, Toshiba, and Google, whose devices would ultimately prove irrelevant. The company shut down Icera in 2015 as part of a broader retreat from mobile while ARM’s GPU instruction set, Mali, approached 50% share of Android smartphones.

As it turns out, the opportunities and threats from CPU/GPU integration were overstated with respect to Nvidia. Tegra never got as big as management expected but gained enough traction in automobiles (infotainment/navigation) and edge computing devices that it turned into a decent sized business that today generates ~twice the revenue that Nvidia’s MCP segment did at its peak. Meanwhile, repeated speculation that steady improvements in Intel’s and AMD’s APUs would decimate the market for discrete notebook GPUs has proven wildly inaccurate as the escalating performance demands of the top game titles continue to exceed the capabilities of integrated graphics. Intel is now developing its own discrete GPUs.

Intel tried to replicate Nvidia’s graphics and parallel processing capabilities with Larrabee. But it turned out Larrabee’s x86 mini-cores, which made Larrabee compatible with software developed for its ubiquitous x86 instruction set and therefore easier for developers to adopt, couldn’t compete with the parallelism of high-end GPUs from Nvidia and AMD. The project was put on ice before its planned 2010 launch11. Intel pressed the brash claim that Larabee’s successor, Xeon Phi, could handle volumes that GPGPUs could not, but alas, Xeon Phi was discontinued last year due to weak demand and delays in ramping 10nm production.

Anyways, notwithstanding its success in the narrow market for professional workstations, in 2010 Nvidia was still mostly a gaming graphics company. But that would soon change as researchers brought the horsepower of GPU-laden computers to AI research. The bitter lesson of AI research, according to computer scientist Richard Sutton, is that statistical methods of search and learning that rely on huge amounts of computation are far superior to the expedient of infusing human knowledge into AI systems12. And those statistical methods are optimized using chips specialized for parallel processing (“accelerators”). In training deep neural networks (DNNs), inputs are represented as vectors, which are multiplied by matrices of weights to produce an output, with weights iteratively optimized through training. Matrix math can be broken down into smaller repetitive problems, each of which can be solved independently (they are “embarrassingly parallel”). So starting around 2010, Nvidia GPUs were increasingly deployed in data centers to train neural nets. The share of accelerators in high performance computing sites grew from 24% to 44% between 2011 to 2013, with 85% of those sites using Nvidia GPUs13

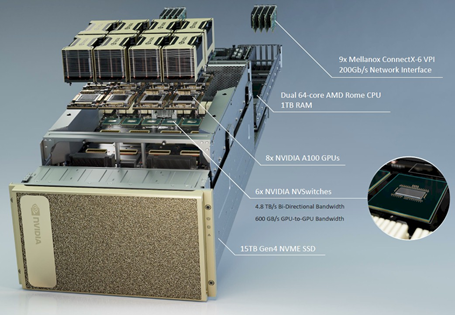

Nvidia’s data center segment (run-rating at $8bn against a $50bn TAM) sells GPUs to server OEMs (HP, Dell), public cloud providers, and through its own DGX AI supercomputer. The latter boxes are sold to enterprises with massive high performance computing (HPC) needs and contain, among other things, a CPU and several GPUs connected by high-speed interconnects.

Source: NextPlatform [NVIDIA DGX A100]

These hybrid servers power general purpose computing on GPUs (GPGPU), where computationally heavy tasks – deep learning, simulation, risk analysis – traditionally handled by CPUs are offloaded to GPUs.

Given the efficiency gains enabled by GPUs, it’s fair to wonder about the extent to which GPUs could replace CPUs. Nvidia’s Tesla architecture promised to reduce the space and energy consumption of large x86 server clusters by 80%-90%. In 2009, one of Nvidia’s oil and gas clients compressed the work done by a cluster of 2,000 CPU servers down to 32 servers containing Nvidia’s Tesla GPUs (the Tesla architecture was renamed Ampere last year)14. Bloomberg replaced 1,000 CPU nodes used to price CDOs with 48 GPU servers.

But another way to think about efficiency gains gotten through GPUs is through the lens of Jevon’s Paradox. As I wrote in my Equinix post from October 2017:

Unit sales of Intel’s datacenter chips have increased by high-single digits per year over the last several years, suggesting that the neural networking chips that [Chamath Palihapitiya] referred to are working alongside CPU servers, not replacing them. It seems a core assumption to CP’s argument is that the amount of data generated and consumed is invariant to efficiency gains in computing. But cases to the contrary – where efficiency gains, in reducing the cost of consumption, have actually spurred more consumption and nullified the energy savings – are prevalent enough in the history of technological progress that they go by a name, “Jevons paradox”…

And I think the “paradox” applies here. Rather than usurping a fixed quantum of work previously handled by CPUs, GPUs are enabling far more incremental workloads. In the mid/late-2000s, investors feared that virtualization technology, in dramatically improving utilization of existing data center infrastructure, would reduce CPU demand. But it turned out that enterprises used efficiency gains to launch a bunch more applications. And to support those applications, they replaced single socket systems with dual and quad socket systems, resulting in more CPUs per server. Similarly, budgets have expanded to accommodate the explosive growth of high performance compute now enabled by parallel processing. GPUs are claiming a growing share of compute cycles but also I think creating CPU demand that otherwise would not have been.

But for GPUs to really take off outside gaming, developers needed to coalesce around software that would allow them to more easily leverage GPUs. The early 2000s attempts at doing so required the unwieldy step of repurposing programs for graphics processing. Nvidia’s proprietary model, CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture, launched in 2006), on the other hand, was just an extension of the ubiquitous C programming language and backward compatible with the 100mn+ GeForce GPUs already in the market. With a captive installed base of GeForce chips, Nvidia could aggressively market CUDA with little downside risk. So a developer with an Nvidia powered computer could just go online and download the CUDA SDK for free and start using it. He might have a program, written in C, that manipulated two arrays serially on a CPU by default. But he could also tell the CUDA compiler to parallel process the task on a Nvidia GPU15. The 10% of a program’s code consuming 80% of runtime could be directed to a GPU instead of a CPU.

The ability to program GPUs was consequential for two reasons. First, like CPUs before them, GPUs became useful across a broad range of applications – medical imaging, financial risk modeling, weather forecasting, oil & gas reservoir scanning, earthquake detection, and other mathematically intense problems – at around the time when CPU performance gains were decelerating.

Second, the CUDA ecosystem created a massive moat around Nvidia. 2008 was a terrible year for Nvidia in some respects. It was forced to slash prices to clear out 65nm inventory. AMD has just launched a new GPU, whose price/performance Nvidia had greatly underestimated and an economic downturn was driving demand for lower-end PCs and laptops, where Nvidia had a weak presence. But beneath that ugliness, CUDA was taking off. Over the next few years, the programming model was embedded in CS curricula at Stanford and University of Illinois – Champaign. Consultants and VARs emerged to help companies develop programs in CUDA and conferences were organized around CUDA. Adobe launched a GPU accelerated graphics renderer exclusive to CUDA.

Sitting on top of CUDA is cuDNN, a library of routine functions commonly used in deep learning applications, optimized for Nvidia’s GPUs. Those functions, in turn, are called by various deep learning frameworks, including the two dominant ones, TensorFlow and PyTorch, to accelerate machine learning applications. Complementing those horizontal tools are AI-powered frameworks that Nvidia has tailored for healthcare, life sciences, automotive, and robotics. For instance, Nvidia’s Drive PX, a computer embedded in vehicles for ADAS and autonomous driving, comes with DNN models that analyze sensor data, while Nvidia’s DriveWorks SDK includes frameworks and modules that developers can leverage to build autonomous vehicle applications.

CUDA’s ubiquity was reinforced by rapid processing power improvements in Nvidia’s chips. From the mid-90s to the 2006, GPU core counts rose by ~2/year, from 1 to 24. From 2006 to 2009, core count quintupled from 24 to 128 and since then have been growing by ~200/year. Ampere, Nvidia’s latest GPU architecture16 – the company develops new chip architectures, named after physicists, that deliver significant gains in performance per watt every 1.5 to 2 years – has 6,912 cores and 54bn transistors, more than double the cores and nearly 4x the transistors as in the Pascal architecture from 5 years ago. It delivers twice the performance and power efficiency of Nvidia’s last architecture, Turing, and the GeForce RTX 30 Series of gaming GPUs that it powers has gotten rave reviews.

But again, performance gains don’t just come from jamming more transistors onto a chip. Nvidia stayed on 28nm far longer than most expected (AMD eventually cancelled its 20nm GPUs too), yet achieved 4x-5x performance improvements on that single node by innovating on architecture, compilers, and algorithms. Nvidia no longer just sells components to PC OEMs but offers industry specific platforms. To speed up neural net training, it has libraries like DALI that crops, resizes and tailors images, and frameworks like Merlin that prepare large datasets.

Being at or near the leading edge in hardware is important but Nvidia’s dominance in high-performance computing is arguably as much, if not more, explained by its enthusiastic embrace of software. Early on Nvidia recognized not only that commoditizing the software complement would drive GPU adoption, but also that tightly coupling software and hardware would result in superior performance. It launched a Fortran compiler to make it easier for universities, financial institutions, and oil & gas companies, whose systems were programmed in that antiquated language, to adopt CUDA. It launched an application development environment, Nsight, that allowed developers to program and debug GPUs alongside CPUs inside Microsoft’s Visual Studio. Today Nvidia has 2.5mn developers programming with CUDA on 1bn CUDA programmable GPUs.

OpenCL, an open, hardware agnostic alternative to CUDA that allows developers to write programs to GPUs, CPUs, and other computing devices from different vendors, wasn’t released until 2009, 3 years after CUDA, and its modular, hardware agnostic positioning resulted in inferior processing at a time when HPC applications demanded the best. ATI launched a GPGPU initiative in 2006, but its Stream SDK faltered under AMD’s ownership. In 2012, AMD and others tried to push open source APIs for heterogeneous systems with the ambitious but ultimately doomed aim of creating an intermediate compiler layer that would allow high level code to run on any processor architecture. AMD’s Radeon Open Compute Platform (ROCm) hasn’t caught on either, even with the company offering tools that translate CUDA into ROCm native code, which makes me skeptical about the analogous oneAPI initiative that Intel is now pushing (Intel also launched a free deep learning inference optimization toolkit, OpenVino, 3-4 years ago that seems to be gaining some traction, we’ll see).

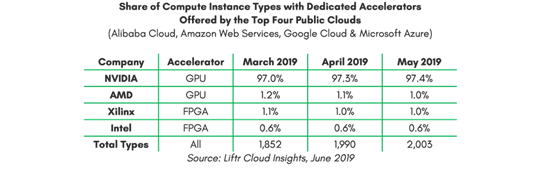

Today, Nvidia’s vertically integrated hardware/software stack is the de facto standard for parallel processing. Its GPUs saturate cloud data centers, edge servers, and workstations. CUDA has been downloaded more than 20mn times. The company has a dominant position in neural net training and a near monopoly on accelerators used by the 4 largest public clouds.

(link)

It’s not just that Nvidia has layered software atop its GPUs. Software is part of a larger philosophical attitude about owning more parts of the technology stack.

In gaming, for instance, besides the bread and butter stuff – ensuring Microsoft’s game development APIs (Direct X) run flawlessly on its GPUs; staffing engineers on the premises of the leading game engines, Epic and Unity, to push improvements in middleware SDKs and ensure compatibility – Nvidia has other gaming specific technologies. Its G-SYNC module synchronizes frame rates to the GPU to resolve tearing (where the screen contains graphics from 2 or more separate frames) and stutters (seeing two of the same frame). Nvidia Reflex – a suite of GPUs, G-SYNC, and other APIs – optimizes rendering pipelines to reduce latency (the response time between a player’s mouse/keyboard taps and resulting pixel changes on the display) for competitive games. The technology is or will be integrated with Apex, Fortnite, Call of Duty, and other AAA games and made available through Nvidia’s Game Ready Driver (a program that provides updates on new game releases) to an installed base of 100mn+ GeForce players17.

Further up the stack, last year Nvidia launched a freemium cloud gaming streaming service, GeForce NOW, that competes with Google’s Stadia, Microsoft’s xBox Game Streaming, and Sony’s PlayStation Now. With GFN, games can be accessed through lower-end PCs (Mac and Windows) and devices (Android, Chromebooks), opening the gaming market to consumers who want to game but aren’t hardcore enough to invest in a gaming rig. The service has 10mn registered users and more games than any other streaming service. Besides streaming games, a gamer can livestream his play with Nvidia’s Broadcast app, which is supported by Nvidia’s GPUs and uses AI to enhance standard webcams and mics – cancelling unwanted noise, blurring the background, and tracking head movement – for high quality broadcasting. So anyways, Nvidia offers a slew of technology and services that are optimized for its GPUs18.

Finally, Nvidia recently launched in open beta Omniverse, a digital collaboration space where designers can create and simulate 3D gaming worlds or designs. BMW is using it to create digital twins of its production factories; WPP, an ad agency, to replace physical shoots with virtual productions. Omniverse reinforces the Nvidia ecosystem as the data synthetically generated inside it can be used to train ML models further up the stack.

Nvidia is also taking top-to-bottom control of the data center, framing the basic unit of compute as the datacenter itself:

“…we believe that the future computer company is a data center-scale company. The computing unit is no longer a microprocessor or even a server or even a cluster. The computing unit is an entire data center now. (Jensen Huang, Nvidia CEO, 2q21 earnings call)

It is no longer sufficient to merely think at the level of a chip. AI is too big for that. You need a data center…its server nodes and the connections between them. Hence, Nvidia’s $6.9bn acquisition of Mellanox last year and its pending acquisition of ARM.

(more on this in Part 2)

Disclosure: At the time this report was posted, Forage Capital owned shares of MSFT. This may have changed at any time since.

- GPU dies have gotten larger over time to accommodate more cores (Nvidia’s A100 GPU, based on its Ampere architecture, has a die size of 826mm2 compared to its GeForce 6 and 7 series from 2004-2006, sized at 196mm2).

- Per Nvidia: “This is computationally intensive. There can be millions of polygons used for all the object models in a scene, and roughly 8 million pixels in a 4K display. And each frame, or image, displayed on a screen is typically refreshed 30 to 90 times each second on the display”.

- Dell workstations powered by Nvidia GPUs were selling for less than 1/10 of a comparably performant Onyx supercomputer sold by Silicon Graphics, who was forced into Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2009. Since the early 2000s, Nvidia’s Quadro line of chips has commanded 80%-90% share of powerful workstations used in computer-aided design and video editing.

- A “northbridge” coordinates communication between the CPU and latency sensitive components like memory and graphics, and a “southbridge” handles communication between the CPU and relatively less performance sensitive components like networking chips, hard drives, USB ports, audio interface, etc. The northbridge would eventually be obviated away as the memory controller and GPUs were combined on the same chip (Intel’s Core chips, based on Sandy Bridge architecture and released in 2011, put the CPU and GPU on the same chip; AMD’s Fusion did the same).

- Per the Harvard Business School case study “Reversing the AMD Fusion Launch”, by 2006 Intel had 40% share of the graphics market (integrated and discrete), while ATI and Nvidia had 28% and 20%, respectively.

- $4.2bn cash / $1.2bn stock.

- where Nvidia licensed graphics patents to Intel and Intel licensed its Front-Side Bus (FSB) and Direct Media Interface (DMI) (a front-side bus carries data between the CPU and the northbridge. A DMI connects the southbridge and northbridge).

- that entailed Intel paying Nvidia $1.5bn over 6 years for access to Nvidia’s graphics IP, to be used in its integrated graphics chips.

- the company ceased development of Intel-compatible chipsets in 2010; the ION chipset for low-powered netbooks was discontinued.

- this article speculates that Nvidia only went with ARM after failing to obtain an x86 license, but as far back as 2009 Nvidia’s management was talking about ARM as a much more substantial opportunity than x86.

- Many still refer to Larrabee as a dismal failure (it was put on ice before its 2010 launch), though Tom Forsyth, the Intel engineer who led the Larrabee effort, insists that Larrabee was never just intended to be a dedicated graphics card, but also a programmable GPU/CPU hybrid for HPC workloads that could buffer threats from parallel architectures that the company’s Xeon CPU was facing.

- See The Bitter Lesson by Richard Sutton.

- Intersect 360 Research Group via Nvidia earnings call (11/7/2013).

- The GPU cluster did 27x the work using the same amount of power.

- PiTorch, one of the two most popular deep neural network (DNN) frameworks, can selectively execute on CPUs or GPUs.

- you can think of an architecture as the way an Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) gets implemented. An ISA can support many different architectures. The AMD Zen and Intel Cooper Lake are two separate microarchitectures, with different performance and power efficiency specs, based on the same ISA. The Ampere architecture is particularly interesting because it does several things – inference, training, data analytics – that used to be run on separate GPUs.

- GeForce RTX 30 Series: Official Launch Event.

- At ~$159bn, the gaming industry generates more revenue than movies, film, TV, and digital music. Games are becoming more graphics intensive, more popularized through free-to-play and e-sports, and just, more EVERYTHING as we shuffle into the metaverse. Nvidia’s GeForce is the dominant brand in PC gaming and plays a central role in enabling all of this.

Pingback: Company Deep Dives – Sharath Bobba

Small thing but I would also add that NVIDIA powers the physics engine via PhysX for the Unity and Unreal game engines which creates further lock-in in the gaming ecosystem. – Vrushank