Let’s take it back to ’69. The Unix operating system was just conceived under Bell Laboratories, the vaunted research joint venture of AT&T and Western Electric. Protected by the strictures of a consent decree from 1956, which prevented its parent AT&T from commercializing technology that wasn’t related to telephony, Unix thrived as an open research […]

[RHT – Red Hat] On A Bridge Between Clouds

Posted By scuttleblurb On In [RHT] Red Hat | Comments DisabledBlurbs [Media trends, Enterprise blockchain]

Posted By scuttleblurb On In Podcast Blurbs | Comments DisabledCode Media (2/14/2018; Analyst Michael Nathanson on where media is headed)

Michael Nathanson

“Over the past 4 years [from 2013 to 2017], the FANG stocks have added $1.4tn of market cap. At the same time, the media industry, the content network industry, the studio industry, has lost about $40bn of market cap.

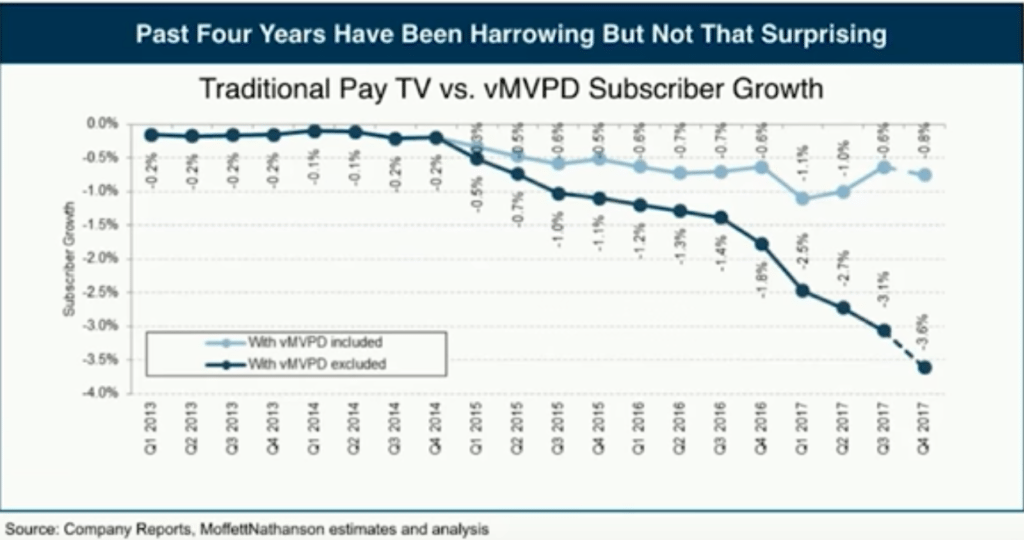

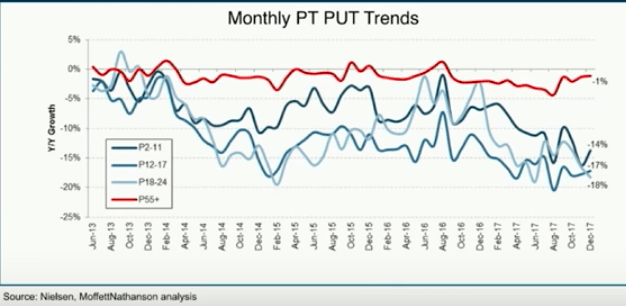

This is one of the most important slides we have at our firm that looks at the pace of cord cutting. Anytime we write a note that says ‘cord cutting’ we get like 1,000 reads…it’s everyone’s favorite topic, but it’s actually kind of complicated because there’s two kinds of cord cutting. If you look at that dark blue line that’s falling pretty rapidly, that’s the rate of cord cutting for traditional distributors. So that’s Comcast, Charter, Dish, DirectTV…so that’s declining at 4%…and we think in 2018, it gets worse…

But, there’s something called the virtual MVPDs, that’s Hulu, YouTube TV, Sling, DirectTV Now…if I added the growth we see at those places, 4mn subs by the end of 2017, we think the rate of change is +/- 1%….we see a two-speed world. If you are only tied to traditional distributors, you’re looking at -4%/-5% rate, if you’re lucky enough to be carried by those virtual new distributors, you’re looking at -1%.

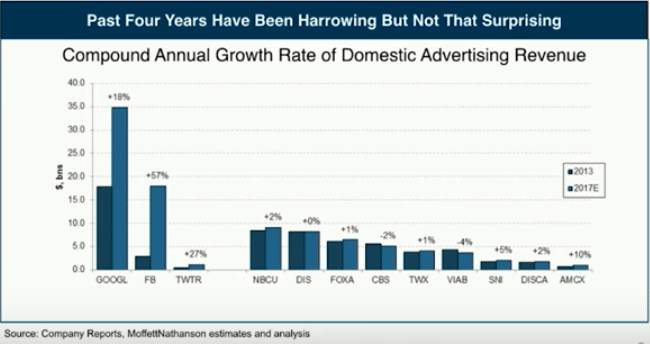

Now, this is more worrying to me. Over the past 4 years, Google’s advertising growth has grown by a CAGR of about 18%. So Google was twice as big as NBC Universal’s advertising base 4 years ago, now their 4x as big as NBC’s advertising base. Facebook has grown by an annual growth rate of 60% over the last 4 years, Twitter’s grown by 27%. Facebook was at one point almost as big as Viacom’s advertising rate, now it’s 4x as big…

In a healthy economy, in a non-recessionary cycle, we’re looking at 0%-2% annual advertising growth rate for traditional media companies, and that’s truly worrying.

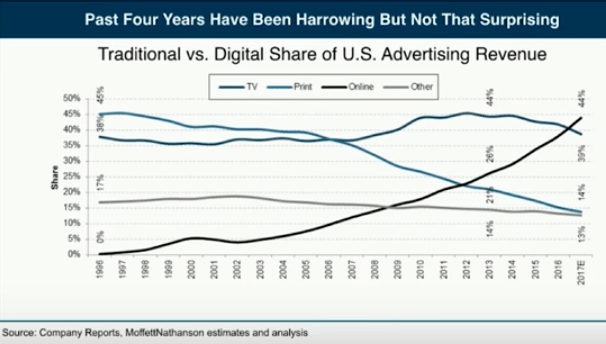

TV for the most part has held in really, really well…up until recently. 2017 was the first year in which digital advertising was a bigger segment than TV advertising.

What’s happening is that digital has done an amazing job on long tail, SMB, direct response. Facebook said a couple years ago that 25% of their advertising base [come from] their top 100 advertisers. Why does that matter? If you asked CBS or NBC, the top 100 advertisers are about 60% of their ad base. What Facebook and Google have done is they’ve monetized the long tail of non-brand direct response dollars and have done it at a great, great rate.

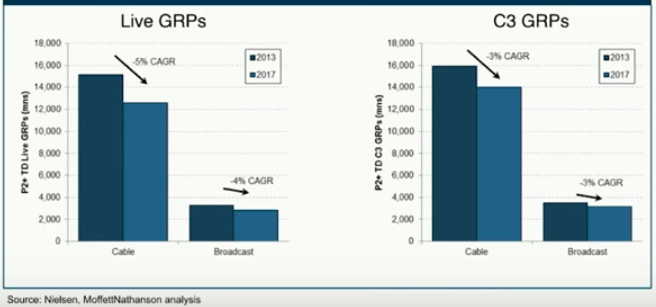

…why you’re getting that soft advertising story in TV is that the ratings just aren’t there.

(the growth of SVOD – Amazon, Netflix, Hulu)

So last year Netflix spent $6.3bn on their P&L buying content, mostly television. Their going to move to film, they’re making 80 films this year. When you look at their P&L this year, it’s $7bn-$8bn of content spending, on a cash basis it’s $10bn-$12bn of content spending. When you line that up with the biggest conglomerates, it’s quickly passing Time Warner, it’s bigger than Fox. They’re reaching a size of investment spending that really challenges linear scripted networks. Now when I back off sports, you could argue that their spending on content’s actually bigger than everyone else but NBCU in 2018.

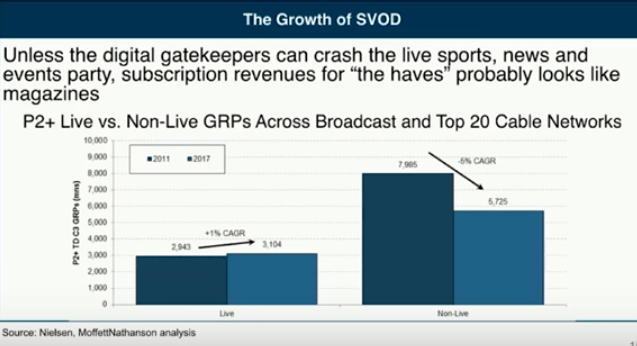

The viewing of live content over the last 7 years (below) has essentially been flat. On the flip side, the viewing of non-live content is down by a CAGR of 5% and that’s accelerating in 2017.

The only products out there that are capturing a high percentage of Americans in one fell swoop is live sports. Our view is that the only advertising play that’s going to be valuable long-term is this live reach of live sports…having this type of unduplicated live reach is why the dollars have not come out of TV yet.

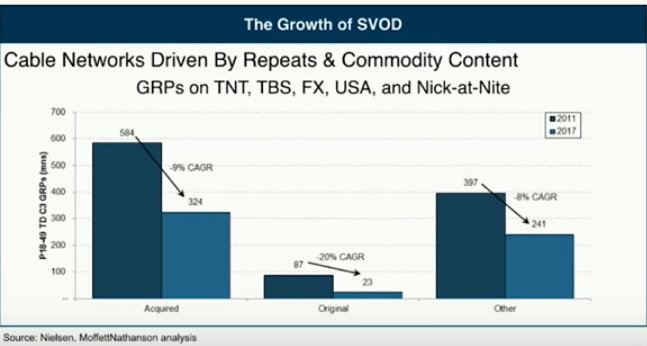

Cable networks driven by repeats and commodity content are in trouble (TNT, TBS, FX, USA, and Nick-at-Nite)…at some point networks that are built on repeat content are going to see big erosion and in fact, that’s what’s happened.

(virtual MVPDs and escalation of affiliate fees)

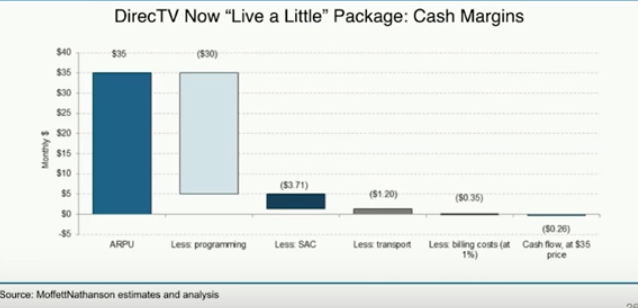

The only problem we see is this…when we do the math on skinny bundles – sports and news stripped down to $35-$40 – our math says there’s no profit there. So you’re getting this profitless growth on the distribution side…

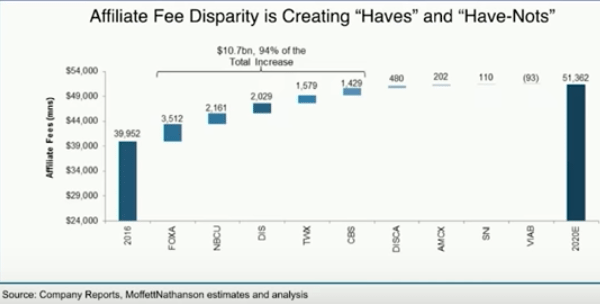

…now making it worse in the future is that the networks they’ve chosen to be the bedrock of those virtual services – Fox, NBC, Disney, Time Warner, CBS – is pretty much where all the growth in that affiliate fee bucket is…the growth rate for their affiliate fees is 9% in aggregate. If you’re a virtual network, you have a $35 price point, but your cost of goods sold is going to be inflating at a very, very high rate, so at some point you have to decide whether you raise your pricing, which could limit your growth or you absorb it as a loss leading product.

PUT – People Using TV. “Did you use TV today”. If you’ve got a network built on 55+, you’re not seeing the same level of decay as these younger networks.

(Film)

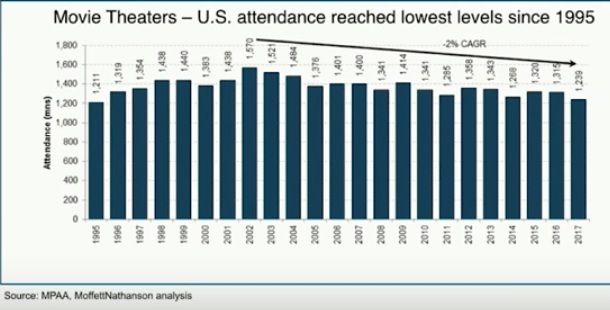

Not a surprise that the physical bit of video has fallen from $16bn to $6bn…but what I’m here to tell you is the growth of the digital format – electronic sell-through, video on demand – is starting to slow. We once thought that could add back the decline of physical. It’s not happening. The bulk of [the physical DVDs] that are bought are from Target, Wal Mart, Best Buy, and it’s just a matter of years before those companies start downsizing their carrying of physical product. So we’re very very worried about the back-end monetization of the film business. And that’s going to lead to more premium VoD….2017 was the worst box office year we’ve seen since 1995 and as Netflix spends more money to make better and better movies, as premium VoD windows start opening up, we see pressure on the theatrical side of the business.

In the short run what you’re seeing is consolidation at a rapid pace. Fox-Disney happened out of nowhere. Time Warner-ATT out of nowhere. Scripps-Discovery, quickly…people are trying to find cost synergies, scale against distributors, trying to find some ways to the consumer with enough library of content.

Blockchain Innovation (10/20/17; How RedHat is Quietly Transforming Enterprise Blockchain with Rich Feldmann)

Rich Feldmann

“So, first on Red Hat. Red Hat is the worldwide leader in open source technology for the enterprise and a lot of the early block chain start-ups were…forming their own open source community projects to develop a distributed ledger either for the cryptocurrency side or for use in the enterprise. So, we got a lot of invitations to come and have conversations with ‘how can Red Hat help me form a sustaining open source community effort and then once I do, can you help me with governance and licensing’. These are all areas that Red Hat was founded on, so it was a natural. So, for about 6 to 8 quarters, those were the nature of the conversations that we had.

Roll forward to today, we have an in-market offering that we call Blockchain-as-a-service that builds on some of the other capabilities that are already in market…blockchain has board level attention at Red Hat and we are putting resources behind it.

What Red Hat’s interest in the blockchain space is distributed ledger use cases for the enterprise. We’re not investing a whole lot of time and energy in cryptocurrency side…so you made mention of the consortiums, Hyperledger (150+ members) and Ethereum Alliance (over 200 members), there’s a few others like Dockchain in the healthcare space, there’s similar ones that are being spun up in Europe and Asia, and I would say virtually all have come to Red Hat and said…’would you be interested in running a support model around my distributed ledger’…while Red Hat sees this as a strategically important initiative, at the current time we don’t have plans to release a Red Hat Enterprise blockchain.

What…are the challenges to getting blockchain or distributed ledgers more broadly accepted, the consortium efforts are a wonderful one and we are members of the Hyperledger consortium, we’re looking at the Ethereum Alliance, but in order [to get] broad based acceptance, eventually we believe that somebody’s going to need to step up and provide a governance model and support model. That’s not Red Hat today. What we do believe is that any distributed ledger…all need to run on a supported enterprise infrastructure, so that’s a supported operating system, being deployed in a cloud or hybrid environment….so what we announced about 6 months ago was a hybrid cloud offering called blockchain-as-a-service with our good partner BlockApps.

If Red Hat’s strategy is not to release Red Hat Enterprise blockchain, what is Red Hat’s strategy? It’s really about providing an enterprise ready platform for you to run your distributed ledger application on…So what we announced, which is something that Microsoft had previously announced with BlockApps, the worldwide leader of what’s known as Blockchain as a service, it’s a way to quickstart a PoC, in a 6 to 12 week project you can spin up your use case, develop it on an application, develop a set of APIs, and develop a small, working application. What Red Hat has done is taken from just a PoC capability to an enterprise ready capability by integrating it with our PaaS offering, which is called OpenShift, so that when clients get ready to go from PoC to production systems, they’re already deployed on those enterprise ready systems […]

Probably smart contracts are the ‘X’ factor, the killer app in distributed ledgers for the enterprise, and smart contracts are now being integrated, they’re a core part of the Ethereum stack and they’re now being integrated into Hyperledger as well, and some of the other distributed ledgers for the enterprise. From an infrastructure perspective, that’s the killer app. What is the killer app from a use case perspective, I don’t think there’s one…

Where we find success is deploying distributed ledger technology behind the firewall that doesn’t require 500 parties to agree on a technology standard…let’s do something like think about a large financial institution that does a general ledger consolidation, and all the steps in the process that occur along the line, whether you’re a subsidiary or a branch of a bank, you’ve got to consolidate your financial statements over say 500 or 5,000 different entities…Now today, with the OCC and everyone that’s looking over your shoulder, you’ve got to report who made changes to that data all along the line. So, that kind of process, completely behind the firewall, under the control of financial institution, is something that lends itself very well to a blockchain or distributed ledger system […]

I’m talking to many large and small systems integrators, large and small ISVs that want to develop applications that will sit on top of a distributed ledger technology. My view is that in the fullness of time, what is a distributed ledger? It’s a database, it’s a data store where some component of the data, ownership, rights pass from one node to another.”

[CMPR – Cimpress NV] Scale Economies and Hard Realities, Pt. 3

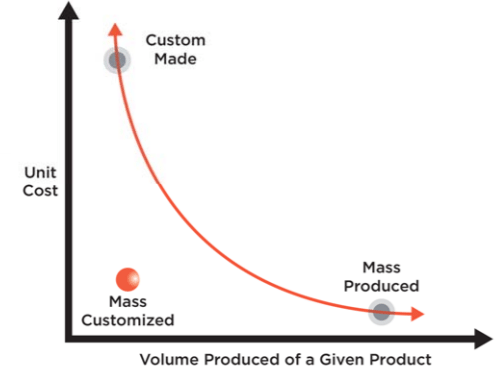

Posted By scuttleblurb On In SAMPLE POSTS,[CMPR] Cimpress NV | Comments DisabledCimpress is a fine business that has been in search of strategic direction for the last 6-7 years, groping for the right balance between value-added customization and low-cost production. These two sources of differentiation are often at odds because the scale economies required to claim a cost advantage depend on running lots and lots of volume across significant fixed costs, a process that is best suited for homogeneous products that share a common manufacturing base and process. You can imagine casting a single widget SKU over and over again. There are no incremental set-up costs from line changeovers. The assembly line just keeps humming as long as it can, spewing a stream of identical widgets onto a continuously flowing conveyor belt, the upfront cost of heavy equipment diffused over more and more manufactured units. At the other extreme, a stylist’s average cost per haircut stays roughly the same, whether he does 20 haircuts a day or 30. Of course, most jobs fall somewhere between these two poles. Cimpress (originally known as VistaPrint), which makes a variety of customized physical marketing materials – business cards, signage, apparel, gifts – for mostly micro business with fewer than 10 employees, claims that it can capture the benefits of both differentiation and low-cost (“mass customization”):

Source: Cimpress Business cards are a perfect use case for mass customization because from the customer’s perspective, a set of business cards, tatooed with a unique logo and font, is unique; but from Vistapint’s perspective, the core manufacturing process and materials required to produce them is essentially the same across all customers. And after its founding in 1995, Cimpress spent the first dozen or so years of its existence focused on paper-based products…business cards (where it remains dominant) postcards, brochures, presentation folders, data sheets, and the like, predominantly in North America. Volume brought scale, scale compressed average unit costs, profits from cost advantages funded VistaPrint’s strategy, which was to litter inboxes with cheesy marketing campaigns offering something like business cards or return address labels for free and drawing customers to the website, where they could then be cross-sold other products and bamboozled with exorbitant shipping costs on the check out page (after they’d already spent the time designing their items and were psychologically committed to the purchase).

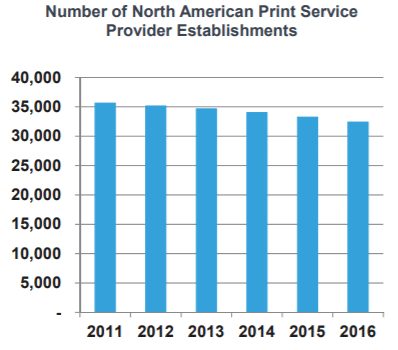

Today, Vistaprint prints 6bn business cards a year, one for nearly every person on the planet. It can produce a pack of business cards in less than 10 seconds and fulfill the order in less than 2 minutes. No one else comes anywhere close to extracting the scale economies enabled by that kind of volume. Although paper-based marketing, including business cards, is in decline, the company’s Vistaprint segment is still showing high-single/low double digit organic growth as it continues to steal share from the tens of thousands of small manual operations that still account for most of the putative $30bn market opportunity [per management; computed as 60mn small businesses with fewer than 10 employees across North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand multiplied by $500 in annual marketing spend], leaving Cimpress, with just $2.4bn of total revenue, plenty of runway ahead.

But sometime in 2011, with revenue growth decelerating, management embarked on an aggressive M&A strategy. Since fy11 (fiscal year ends June), on top of ~$590mn in capex and capitalized software development, management has spent around $900mn buying 15 companies – ranging from a DIY website building (Webs.com) to a host of European print and design companies catering to graphics professionals (consolidated as the “Upload and Print” operating segment) – tangentially related to the core Vistaprint business by dint of their marketing orientation but otherwise diffuse in terms of product SKUs and addressable markets. And for this ~$1.5bn investment, Cimpress’ EBITDA (after stock comp) has grown by just $106mn, a 7% pre-tax return compared to management’s 10% hurdle rate for predictable organic investments in developed countries and 25% bogey for riskier investments in emerging markets. Now, one might argue that the cost structure is larded with growth opex that will eventually subside. But, we’ve also heard this line from management before, as it has fumbled its way from one strategy to the next.

The first course correction came in fy11, when management recognized that deep discounting, aggressive cross-selling, and cheap checkout tricks were compromising repeat purchase rates, diluting lifetime customer values, and attracting low quality customers looking for an easy deal…basically, a leaky bucket that required constant infusions of customer acquisition spend that management did not think was sustainable. And so, Cimpress made significant investments in packaging, product quality, and user experience on the site. It dramatically reduced what it charged customers for shipping, which at the time apparently made up a “very material portion of revenues”, and introduced less jarring discounts on more transparent list prices. These actions were meant to chase away the cheapskates who only cared about price, leaving the company with a more loyal and satisfied core more apt to repeat purchase. Didn’t really work. Despite some operational improvements – quality complaints, production throughput times, late deliveries all improved – organic revenue growth slowed from 22% in fy11 to 20%, then 12%, then 4% over the subsequent 3 years. Gross margins declined a bit, EBITDA margins declined a lot. Buyer repeat rates actually declined from 30% to 26%. Management’s initial expectations for $5 EPS (representing 20% annual growth over 5 years) and $2bn in revenue by fy16, would clearly not come to pass. That brings us to Act II.

Sometime in fy13, the company embarked on an effort to disaggregate its tech platform into a set of software microservices appropriately named the Mass Customization Platform (MCP) as part of a broader effort to centralize all sorts kinds of functions – product management, order routing, fulfillment, commodities procurement – across its 20+ brands:

“…our vision for MCP is to be a constellation of modular, reusable and independently functioning software components and related services which is analogous to a well-organized set of interchangeable Lego blocks. This platform will sort millions of heterogeneous incoming orders into homogeneous specialized production streams which, thanks to the automated workflow and the regular repetitive production steps we can enable, will embody the principles of mass customization. Yet, the overall platform needs to remain reconfigurable and modular to ensure the relevance to a wide variety of applications….what we are doing is we are frankly trying to break the businesses which we bought, not just Vistaprint, but each of the individual companies we bought, into the component parts of the merchant, the customer-facing business unit with the brand and the fulfiller, and then to reconfigure all the IT systems so that those can…act as a routing layer between those.” – Robert Keane, Chairman and CEO (Cimpress Investor Day, 8/10/2016)

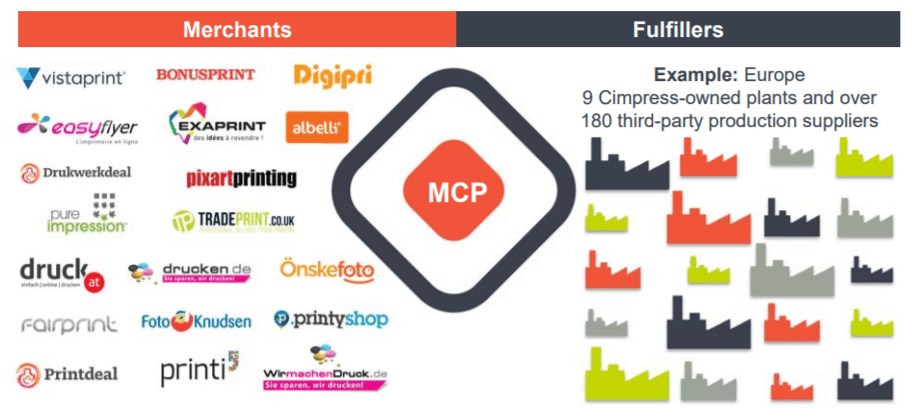

Management’s big idea was to create a matchmaking service that would pair the unique, specialized, and often small-sized manufacturing and fulfillment needs of its sprawling internal businesses (“merchants”) – some selling business cards to micro-businesses in the US, others serving graphic design pros in Europe who in turn serve micro-businesses – to its most cost effective option among a network of in-house and third party production plants and shipping/logistics providers. As the number of fulfillment partners joining the platform expanded, so too would the number of SKUs the company could offer, which in turn would attract still more fulfillment partners seeking production volumes to run through their specialized plants. Two-sided engagement would lift volumes flowing through Cimpress’ network, bringing procurement leverage to bear against service providers, equipment vendors, and commodities suppliers.

But just 5 months after promulgating this lofty vision during 2016 Investor Day, management conceded that this centralized model, which was intended to increase speed to market and production flexibility, had instead bogged down the company with complexity and bureaucracy. It announced plans to retreat back to a more decentralized organizational setup wherein production, fulfillment, and product management would be siloed once again by brand, though non-core corporate functions (finance, legal, major capital allocation), procurement, and the modularized technology platform would remain as shared services across banners. Now the thinking is that decentralization will unleash “entrepreneurial energy”, ensure accountability for results, and improve customer satisfaction. And that’s where we are today. Mistakes have been made, that much is clear. The company’s acquisition of DIY website builder Webs.com, one of it’s largest, seems particularly ill-conceived. Website building is a high gross margin business that pure-plays struggle to monetize because lofty customer acquisition costs eat up all the profits. But Cimpress believed it could do away with much of these advertising costs by cross-selling web services into its existing customer base, because in management’s own words “…a website is the same as a brochure, but it’s a digital version of that.”

But of course, a website is more than just another marketing tool that you toss into the shopping cart as you purchase signs and business cards; it’s increasingly the entire digital storefront and a critical system of record. The companies that do well in website building either own critical on-ramps like domain registration (Godaddy) or offer kick-ass functionality further up the stack, with sophisticated, friction alleviating technology and/or 3rd-party app integrations (Wix and Shopify). And there’s a reason why website builders don’t bundle business cards…not only are these offerings not a natural point of integration, but doing well in either area involves entirely different processes. I’m not rehashing Cimpress’ somewhat ignomonious capital allocation and strategy choices with snark (or I at least hope it doesn’t come across that way). On the contrary, I think it’s admirable that this management team at least attempts to take an earnest look at its shortcomings, fesses up to them, and experiments with new ideas. I bring this up just to frame the difficulty of growing through a continuous product introductions and simultaneously extracting scale economies.

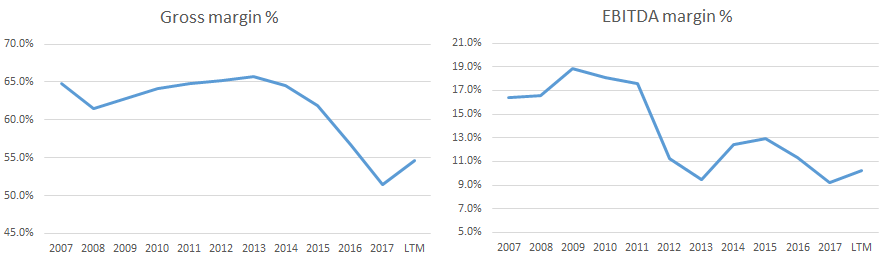

At one extreme, the company could have just stuck to business cards and closely related paper-based products, gaining a little more production leverage every year and steadily improving its gross margins…but growth would have inevitably slowed and then reversed as the market for business cards is in decline and Cimpress’ business card revenue growth has decelerated significantly over the last decade. But then, proliferating product categories to boost volume growth makes scale economies harder to come by. Through the acquisitions that now comprise its Upload and Print segment, Cimpress multiplied its SKU count by 300x, and the number continues to grow at a rapid pace. The scale benefits attending homogeneous manufacturing and fulfillment processes attenuate as you start offering different substrates and formats, and especially as you expand into banners, apparel, pens, magnets, and other trinkets made of entirely different materials, manufactured through a different process with different equipment in different countries. I think the company recognized this long ago, hence its emphasis on higher quality products to customers with better lifetime values; but I also think it’s fair to say that management underestimated how difficult it would be to reap the benefits of mass production over so many diverse product categories. Check out their margins over time…

The nosedive in gross margins can be mostly explained by investment in design services and a mix shift towards Upload and Print, which has been growing faster than Vistaprint and is more dependent on outsourced production. But, this segment also has lower sales and marketing costs per order than Vistaprint and all else equal, the two segments should have comparable EBITDA margins…but those have declined considerably as well over the last decade, even as Cimpress has shown some sales & marketing and G&A leverage over time. I think this can be at least partly explained by shipping, which runs through gross profit. The company is loath and perhaps embarrassed(?) to reveal how much money it was making on shipping, but assuming average shipping price charged to the customer of $10 and an average order value (back when management still revealed this figure) of around $35, it was clearly significant.

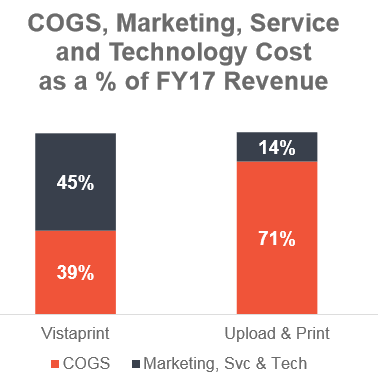

I don’t imagine its own shipping costs have changed by nearly as much, and so providing relief to its own customers likely translates to a mostly direct gross profit hit. Also, losses from the “all other business units” segment, which houses speculative investments, emerging markets, partnerships, continue to grow, from -$9mn in fy16 to -$36mn LTM. Finally, digital products and services (Webs.com I assume?) has witnessed significant revenue declines. Except for maybe losses in emerging markets, which are still small and sub-scale, none of the above mentioned causes of margin compression will reverse, so the high-teens EBITDA margins of the mid/late 2000s are likely a thing of the past. Management does not deny this and, in the face of persistently declining margins, now directs investors to think instead about dollar profits, retention rates, and lifetime customer values, tacitly acknowledging that ever more of the scale benefits are shifting from production leverage to value-add per customer. Cimpress’ last 10-K (year ending June 2017) reveals 17mn customers served by Vistaprint, which means the number of unique customers hasn’t budged since fy14. However, Vistaprint’s revenue has grown by over 25% over that time, implying that revenue per customer has gone from $65 to around $80. Management does not break out gross profit or opex by business segment in its financials, but we do have this useful exhibit from the last Investor Day:

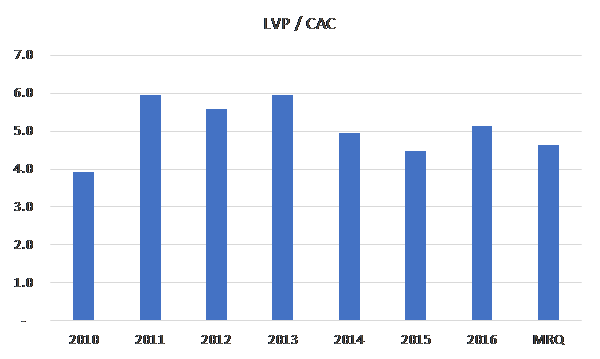

The buyer repeat rate, at between 30%-35%, is so low that one wonders whether the lifetime value of customers is really the right metric for management to focus on, but let’s just go with it. So if revenue per Vistaprint customer is $80, then it looks like gross profit per sub is close to $50. Assuming a 10% discount rate and that 35% of buyers make repeat purchases [I’m assuming it’s higher than the 31% rate the company disclosed for fy17] implies an LTV per customer of $73. Before the company went on its acquisition spree and it was just basically Vistaprint, the cost of customer acquisition was around $24, suggesting an LTV:CAC of ~3x. Once you factor in higher recurring costs of supporting today’s relatively higher quality customers, the ratio is probably closer to 2.5x(?), right at the cusp of acceptability. To put that in perspective, Trupanion is at ~4.5x, Godaddy is over 5x. [Founder and CEO Robert Keane writes the kind of letters that value investors just eat up, chock full as they are of Buffett-esque straight talk and verbiage. But I’ve actually found disclosure to be frustratingly inconsistent. For instance, up until fy14, the company provided metrics on average order values (AOV), order volumes, repeat customers, bookings per repeat customer, and other good stuff. They stopped regularly disclosing most of this in fy15, defending the move by maintaining that a metric like $AOV doesn’t provide much insight because there are so many businesses besides Vistaprint. Like, huh? Vistaprint still represents 65% of revenue, 80% of segment profits, and the majority of organic investments. And even if that weren’t the case, why stop disclosing the very data required to estimate lifetime value at precisely the time in the company’s history when it is explicitly targeting this metric?]

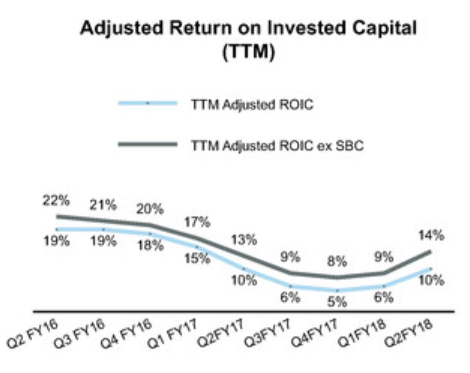

As mentioned earlier, Cimpress’ acquisitions and organic investments over the last 5-6 years appear to have impaired value, with returns on incremental capital falling short of capital costs, and over time, we see that the company’s returns have deteriorated rather markedly in even the last few years. And they are way below the the 30%+ returns the company was realizing before its spree. Meanwhile, over the last 5 years, organic growth has been cut nearly in half, from 20% in fy12 to ~10%/11% LTM.

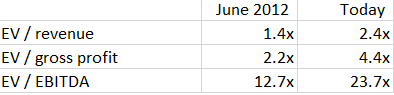

[“adjusted” because the numerator excludes restructuring charges; acquisition related earn-outs, amortization, and depreciation; and impairments] But that hasn’t stopped valuation multiples from doubling over that period.

But perhaps I am throwing excessive shade. While I think Cimpress is a worse company than it was 5-10 years ago and its mass customization platform is maybe not quite what was promised, it’s still hard to imagine a competitor rivaling Cimpress’ scale advantages, and I think the company will continue taking enough share to deliver high-single/low double-digit organic revenue growth for the foreseeable future. Founder and CEO Robert Keane, who owns 10.5% of the company and owns the same number of shares as he did 7 years ago, has significant skin in the game. The company has retired nearly 30% of its shares over the last 7.5 years in the low-$40s. Using the high-end of management’s estimate of investments required to grow free cash flow by at least inflation, LTM mFCFE per share is around $8/share [1], so the stock trades at ~20x, which doesn’t seem too demanding a valuation given the company’s competitive positioning and growth opportunities. Cimpress recently reported an outstanding quarter across all reported segments, suggesting budding traction with its decentralization initiative. But I frankly have no idea if this inflection is sustainable.

Given the pronounced deceleration in core legacy business cards, where the engine of mass customization was applied beautifully for the first 15 years of the company’s life, diversifying into far flung SKUs may have seemed sensible at the time….they were squeezing less juice from scale economies but could compensate for that by moving upmarket, offering a value-added bundle proposition with a heavier service component. But in retrospect, shareholders would probably have been better off if management just maximized the hell out of lower organic growth and plowed excess capital – capital that could not be reinvested into core Vistaprint – into share buybacks rather than acquisitions. [1] Estimating relief under the new US tax law is tricky because the company already reallocates income across a sprawl of geographies to minimize its tax payments. Cimpress derives just 40% of its revenue from the US and over the past year paid just $40mn in cash taxes on $180mn in pre-tax cash profit, so I’m not so sure the new rule will meaningfully benefit the company.

[RP – RealPage] Software Bundle, Not a Platform

Posted By scuttleblurb On In [RP] RealPage | Comments DisabledIn 1998 RealPage Communications, an internet hosting service for the commercial and residential real estate industry, merged with Rent Roll, a provider of property management software, giving birth a few years later to the company’s flagship property management SaaS, OneSite. At a time when property managers were still awkwardly fusing disparate general purpose on-premise systems […]

[IDXX – IDEXX Labs] Priced to Win

Posted By scuttleblurb On In [IDXX] IDEXX Labs | Comments DisabledPeople love their pets. That’s obvious not merely in our impulse to anthropomorphize them but to increasingly care for them the same way we do human members of our families. American pet owners used to really only took their pets to clinics to treat obvious physical symptoms, but they’ve increasingly been hitting up the vet […]

[MSFT – Microsoft] Death Star, Reformed

Posted By scuttleblurb On In [AMZN] Amazon,[GOOGL] Alphabet,[MSFT] Microsoft | Comments DisabledThere’s a good reason why Microsoft was dubbed the Death Star by many fearful detractors during the on-premise era: its OS/application stack, with 90%+ desktop share, was an impermeable force that whipped the surrounding computing galaxy into submission. Given Window’s ubiquity, value added resellers and systems integrators optimized their resources and relationships by supporting Windows […]

[SERV – ServiceMaster; ROL – Rollins] Scale Economies and Hard Realities: Part 2

Posted By scuttleblurb On In [ROL] Rollins,[SERV] ServiceMaster | Comments DisabledCountless termites die every day from natural causes, and that makes them the lucky ones. Many are poisoned by liquid pesticide sprayed along entry routes into homes. Still others are duped into ingesting toxic morsules that they share with nest mates, unwittingly wiping out whole colonies, slowly, over months. More creatively (and less commonly), they […]

[TRUP – Trupanion] A SaaSy Underwriter

Posted By scuttleblurb On In SAMPLE POSTS,[TRUP] Trupanion | Comments DisabledLooking at TRUP is like staring at one of those ambiguous images that could be both a rabbit and a duck, both a saxophonist and a woman’s face: we know that this is an insurance company, but we’re compelled to analyze it as a data-driven subscription service.

Of course, all responsible insurers are data-driven and the recurring nature of premiums also make them subscription-like, but we don’t typically think of insurers as a subscription service in the same vein as a SaaS enterprise. We do for TRUP largely because its management team has diligently trained us to focus on SaaSy metrics. Some of this is just reframing vocabulary: “subscription fees” not “premiums”, “members” not “policyholders”, “Territory Partners” not “agents”.. Trupanion’s ignorance of the insurance industry lexicon – scarcely a mention of reserves, underwriting leverage, medical cost trends, book value – is so obtrusive as to almost certainly be by design (what fast-growing enterprise wants to be seen as a boring insurance company?).

But this is also the first insurer I’ve see that disaggregates retention by member cohort and discloses lifetime value to customer acquisition cost ratios. That’s not a knock on the company. The first principle to any recurring, subscription-like model, insurance company or not, is onboarding customers for far less money than those customers will generate in lifetime profits. With most of the stuff you buy – a haircut, an iPhone – there is little confusion about the value of the product to you. Insurance is a lot squishier because you don’t know at the time of purchase whether you’ll need it. For major categories of insurance – where the covered thing is monetarily significant and its cost readily determinable, as in the case of a car or house, or where it transcends monetary value, as in the case of your family’s health – we easily buy into the collective understanding that in any given year, the premiums from those on whom fortune smiles subsidize those on whom she frowns. We don’t feel like our rights are being trammeled when law mandates we buy such insurance or that we’re being bamboozled when our insurer earns an underwriting profit from this scheme. We’re risk averse and understand that peace of mind is worth paying for and that an insurer should be compensated for giving it to us. But dogs and cats?

While there’s no question that we treat our pets far more humanely than we used to and that pets have graduated from the status of mere property, they still don’t occupy the same sanctified hemisphere as humans and we’re far from consensus on the range of seriously unfortunate health outcomes that we should be willing to prepare for. If you ask your friends about pet medical insurance, as I did, you’ll likely find that only a few have it, maybe half think it a reasonable purchase and the rest may outright scoff. Rather than pay $50 for a Trupanion policy with a 10% deductible, why not just put $40 in the cookie car every month as a sort of pet health savings account? If I’m shelling out $600 this year for a Trupanion policy and eat 10% of the costs, I need to think there’s a 20% chance of at least $6,000 in medical emergencies in the next 12 months for the policy to be “worth it”. [to put that in context, treating hip dysplasia for a Golden Retriever can cost anywhere between $2,000 (if diagnosed early) and $5,000 (if diagnosed late and a hip replacement is required)].

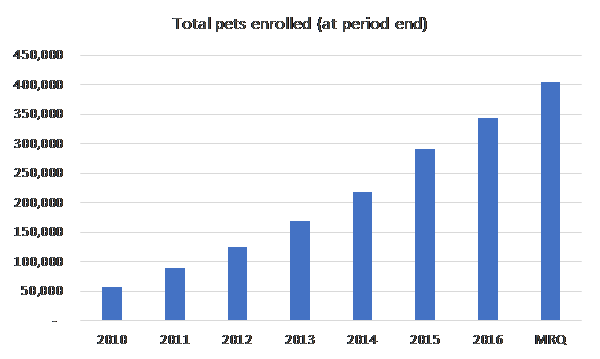

Of course, the decision to purchase insurance can be an emotional one that goes beyond sterile expected value calculations, and the more importance you place on your pet’s life and comfort, the less willing you are to roll the dice…but the point is that on the surface, it’s not entirely clear to me pet owners feel they need insurance for their pets. But can they be made to think they need it? There’s some evidence to believe that they can: the number of pets covered by Trupanion has compounded by 25%/year since 2011 to over ~360k and nearly 85% of members renew their policies every year…and half the lost profits of those who don’t renew are offset by existing members who insure more pets or refer their friends. The proselytizing efforts begin with the 40,000+ vets staffed at the 28,000 vet hospitals across North America (20,000 of which are independently owned and operated) who deliver ~54% of TRUP’s new members and from whom pet owners seek trustworthy guidance. [According this recent Motley Fool interview [3], Trupanion’s CEO claims that when vets recommend Trupanion to their clients, 1 in 4 people enroll.]

Sometimes oblique coverage restrictions, annual payout caps and long waiting periods for covered treatments are buried in fine print; other times, the insurance company and the vet charge based off different fee schedules, with the pet owner paying for the entire procedure out-of-pocket based the vet’s fee schedule only to be reimbursed weeks later by the insurance company using a lower “usual and customary” rate [which is based on fees charged by other physicians in the surrounding area for the same procedure]. A vet probably won’t be blamed for not proactively recommending pet medical insurance, but pushing a policy that culminates in an expensive “gotcha” moment is poison. Trupanion attacks these causes of friction and confusion by:

1/ pricing off the cost of care. Trupanion carefully estimates the cost of medical care across 1mn+ dimensions – species, breed, zip code, deductible, age – and simply tacks on 30% to arrive at the policy price paid by the pet owner…so, a pet owner is basically paying a 30% premium above expected medical costs to rid herself of cost uncertainty. Trupanion then pays out 90% of the vet’s invoice, with no limits per claim or illness. So, it doesn’t matter if one vet charges $2,000 and a rival vet across the street charges $1,000; Trupanion will cover 90% of the eligible treatment cost in both cases. Assuming Trupanion has accurately estimated the cost of care, in aggregate, 70c of every premium dollar Trupanion collects goes to paying vet invoices;

and

2/ re-directing reimbursement flow (in progress). With traditional pet insurance, the patient covers the entire vet invoice upfront and then hopes the check that arrives from the insurer in 2 weeks will reimburse her for the “right” amount. While most of Trupanion’s claims are still paid via check, they are increasingly routed through Trupanion Express, in which Trupanion pays the vet 90% of the bill directly, thereby taking the burden of up-front payment away from the consumer. Express can be integrated into practice management software so that an invoice is immediately shot over to Trupanion, who wires the requested funds into the vet’s bank account in less than 5 minutes. The number of vet hospitals with Express installed has grown from 89 in mid-2014 to 500 in 2015 to ~1,300 today, with over 30% of vet invoice dollars channeled through Express, on its way to 95%+. No other competitor in the space is even bothering to pursue a similar direct payment scheme.

These two changes largely lift the confusion attending discrepant pricing schedules and alleviate the strain of what in some cases could be an enormous immediate upfront payment for the pet owner, followed by an anxiety-ridden reimbursement interval. The member knows his out-of-pocket burden from the get-go and will not be financially surprised down the line. And because a Trupanion member need not wrestle with the financial uncertainty of costly medical care, she spends twice as much on vet services over her pet’s life than an uninsured pet owner…and the vet can simply focus on recommending the best treatment, without also stressing over the owner’s ability to pay.

Even so, considering the history of disappointing experiences with pet medical insurance, it’s no wonder that winning over vets has proven a laborious process. It can take 3-5 visits for a Territory Rep to even get her first meeting…so, if the TR is making 1 visit every 6 months, we’re talking years. Trupanion makes close to 100,000 face-to-face vet visits every year, with 200 hospitals per territory visited every 60 days (with touch frequency now increasing with impending account manager build out), and even after hammering away at vet conversion for nearly a decade in the US, the company still has significant work ahead: against a universe of 25,000 addressable hospitals in the US, only 8,100 are actively recommending Trupanion today, a figure that is growing by ~500-600 hospitals/year. Competitors, on the other hand, continue to take a direct-to-consumer approach, carpet bombing their territories with online marketing to create awareness, which in the absence of vet buy-in has not proven very effective.

Building trust is a time consuming process that requires TRs to persistently contact vets, who must then observe positive customer experiences firsthand. These relationships cannot be bought, but must be earned over time: a vet hospital will not compromise a pet owner’s continuing business for referral fees and besides, Trupanion does not offer kickbacks of any kind to vets for referring patients. You may be surprised to know that with the exception of VPI Nationwide, the largest player in the space with 40% share (vs. #2 Trupanion with 20%), other competitors like Healthy Paws and Pet Plan don’t underwrite the policies they sell. Trupanion’s conceit is that by owning all links in the chain – from sales to underwriting to claims processing to customer service – and forgoing reinsurance, it can provide insurance at a ~20% lower cost than peers. These savings are used to cover a greater proportion of claims costs – 70% of premiums at Trupanion vs. closer to 50% for peers – enabling a “no-fuss” payments experience that induces greater satisfaction from pet owners (who remain Trupanion members for longer) and buy-in from vets (who feel comfortable enough to recommend Trupanion to new clients).

Of course, sustainably profiting off a cost-plus model and credibly delivering on the promise to immediately cover 90% of whatever invoice requires precise, granular insight into the cost of pet acquisition and medical care. Over 17 years since inception, with data from 1.5mn+ claims and over 500,000 invoices/year, Trupanion has amassed cost and retention experience across 1mn+ category permutations…so, for instance, the company understands how the claims experience of a 5-year old bulldog in zip code 11201 differs from that of a 3-year old Shih Tzu in 60047 and can price the two pets accordingly. There are no short cuts to this process. The time required to build claims experience and flesh out statistically significant patterns at such a granular level is a steep learning curve that even a well-funded competitor cannot easily surmount. Although VPI Nationwide has been around longer than Trupanion, their dataset is less robust because they don’t price their policies with nearly as many observations (zip code, for instance) as Trupanion, nor do they cover congenital and hereditary conditions. [to be clear, Trupanion doesn’t cover pre-existing conditions either, but unlike other insurers, it doesn’t refuse coverage on all future illnesses arising because of pre-existing conditions].

Still, while data may be a competitive advantage in the early stages of penetrating a market niche, I’m not sure this in itself constitutes a real moat. Data has to be proprietary, valuable, and part of a self-reinforcing process (data network effects) for it to count as a sustainable edge. There’s a reason why you never hear insurers tout data as a unique advantage…there are diminishing returns to data as the relationship between price and insured risk doesn’t change all that much for granular exposures and eventually becomes common knowledge.

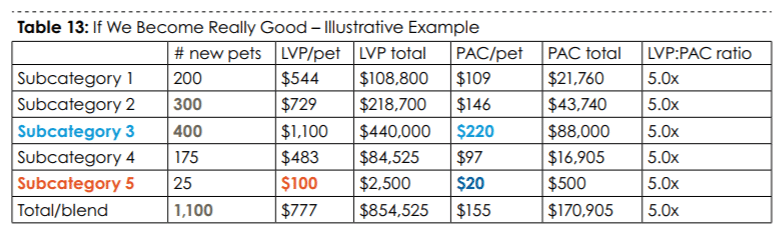

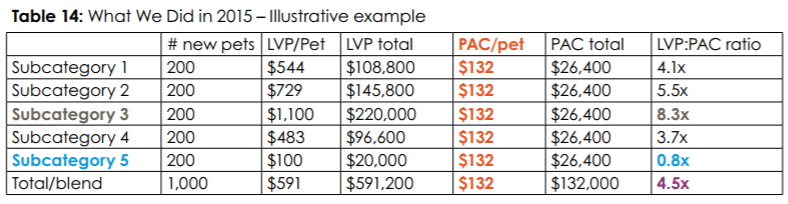

(the Lifetime Value of a Pet (LVP) to Pet Acquisition Cost (PAC) ratio that Trupanion reports every quarter is the blended output of explicit LVP:PAC targets across a slew of subcategories. So, while the lifetime value of, say, a 2-year old cat in Manhattan with a $1,000 deductible will differ from bulldog puppy in Pittsburgh with no deductible, Trupanion can toggle pricing and acquisition spend to get iteratively closer to a common IRR across subcategories, with no cross-subsidization between them. Ideally, the table would look something like this…

Not. quite. there. yet…

…

(Tables 13 & 14 from Trupanion’s 2016 Annual Letter)]

Meager pet insurance adoption rate in North America (< 2% of ~180mn dogs and cats) compared to certain Western European countries (25% in the UK, 50% in Sweden), is an oft-touted part of the bull case. Of course, one wonders why, when pet insurance has been available in America since at least the mid-80s, the disparity exists in the first place? I don’t really know. But one reasonable-sounding explanation I’ve heard is that in Western Europe, pet insurers launched by first winning over vets and those vets then pushed the product to consumers…whereas in the US, insurers started by asking “what price will pet owners pay for this thing called ‘pet insurance’?” and then reverse engineered a product without consulting the vets, yielding something that both consumers and vets hated.

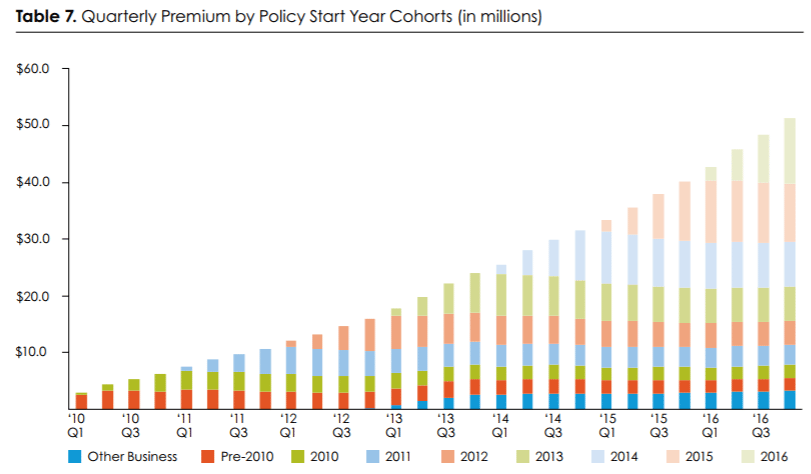

In any case, it doesn’t really matter. I think we just want to see that the method to driving category adoption is sound. In an embryonic market, it’s up to pioneering companies to create the category. Pet medical insurance is so nascent in the US that although Trupanion continues to claim share – there are around 20 brands that make up the pet insurance space, but 2 players, VPI Nationwide and Trupanion, account for 60% of the insured pets – it does so in a market that, against the broader population of insurable pets, barely exists. Rather than look to foreign countries for cues, it seems better to just make a judgment call on whether a) the value proposition for vets makes sense, b) the company has the will and wherewithal to push the ball forward, and c) the product, when discovered and used by the end consumer, solves a real need (including a need the consumer previously didn’t even know she had). a) and c) are tied at the hip since, as previously discussed, vets will only pitch Trupanion if the pet owner perceives benefit. While I harbor doubts about the intrinsic value to a pet owner, those personal reservations are trumped by nearly a decade of data strongly supporting the claim that yes, pet insurance is becoming a thing in the US. As born out over many cohorts, the average life of a Trupanion member is around 6 years…

…during which period the company pulls 20c in variable profit from every incremental premium dollar, reinvesting most of that into acquiring new pets…

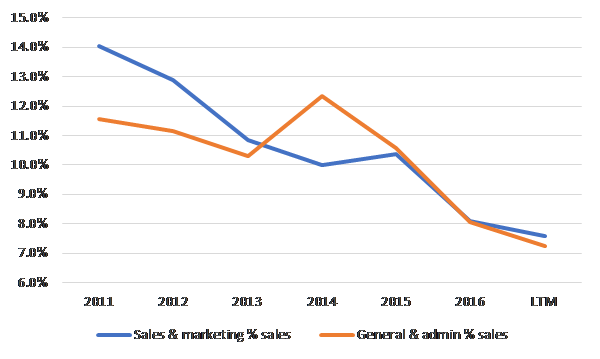

….at compelling lifetime values translating into huge IRRs, leveraging sales & marketing and fixed expenses along the way.

The IRR math works roughly as follows: on average, Trupanion pays $175 to acquire a pet and recognizes premiums of around $53 for that pet each month over 71 months. That 53 bucks is whittled away like so:

Monthly premium: $53

Vet invoices: ($37) [70% of the $50 premium]

Variable expenses: ($5)

Contribution profit: $11 [20% of premiums. The Lifetime Value of a Pet (LVP) is computed off this figure]

After adding back sales & marketing, Trupanion’s trailing 12 month EBITDA margin after stock-comp is ~8%, implying fixed costs of ~12% of premiums [20% contribution margins less 8% EBITDA margins ex. sales and marketing], so 60% of contribution profits are being consumed by fixed operating costs at the moment.

But at scale, which management pegs at ~700k pets (vs. over 360k today growing low/mid-teens y/y), the company thinks it can do 15% adjusted operating margins excluding the cost of adding new pets. When we back off 1%-2% for stock comp, it’s maybe more like 13%. Given the degree to which Trupanion has leveraged its cost structure over the last 6-7 years, I find this claim credible.

And so, at scale…. .

Fixed expenses: ($3)

Capital charge: ($0.6) [8% x (monthly premium divided into a premium:surplus ratio of 6x)]

Profit/pet/month: $7 [13% of premiums]

In other words, the company is generating ~$520 in profits over the average lifetime of a member, around 3x the cost to acquire that member. The cash flow streams over ~71 months impute a 65% IRR. Alternatively, at a 15% discount rate, the present value of cash flows over of a subscriber’s life is ~$330, nearly twice the cost of acquisition. Imputing attractive unit economics, of course, requires a sufficiently wide LVP-PAC spread. The $175 pet acquisition cost that I am using assumes the current LVP/CAC of 4.5x, where it has roughly been for the last 5-6 years. This figure would have to decay to below 2.5x before the NPV of pet acquisitions turns negative (i.e. destroys value).

But I see no reason to expect such a draconian deterioration and in fact, it’s possible that as the company further densifies its markets with vet allies, layering on radio and TV spend may even boost conversion from vet recommendations, as has been true thus far in Trupanion’s mature markets where half or more of vet hospitals actively recommend Trupanion.

Given the unit economics and the runway, it’s not hard to see how things can get interesting [though whether they can get interesting enough to buy the stock at today’s valuation is an entirely different question]. Assuming today’s annual PAC spending of ~$15mn/year grows by a few million per year and even assuming LTV/CAC deflates to below 4x, I can get to just over 800k enrolled pets in year-7, around 12% growth per annum. Absent some “silver bullet for cost effective accelerated organic growth” (company’s words), management seems determined to fund its expansion entirely with internally generated profits.

Applying a pre-PAC scale margin of 13% to implied revenue gets us to around $70mn in pro-forma EBITDA, which, assuming reinvestment, will be growing by low-teens, providing still more ammo for pet acquisition. With 800k enrolled pets against a universe of 180mn dogs and cats in North America, Trupanion will still not have even nicked the surface of its potential…so, still be plenty of opportunity to deploy maybe 40%-50% of pre-PAC EBITDA into onboarding pets at 40%+ IRRs. In theory at least. What you’ve just seen is the rabbit. But what about the duck?

After all, this is still an insurance company and balance sheet strength reigns paramount. But is it and does it? Trupanion’s underwriting leverage – premiums to surplus ratio, a measure of how much underwriting risk you are assuming relative to the capital you hold – is greater than 6x [Trupanion does not reinsure its risk, so subscriptions = gross premiums = net premiums]. Whether this exceeds the standard of prudence depends on the nature of risk being insured. Typically, a ratio greater than 3x is considered unusually aggressive for a P&C underwriter and an insurer with significant high-severity natural catastrophe exposure will keep it closer to 1x. Health insurers, in contrast, will underwrite 7x+ their surplus. In my experience, growth and conservative underwriting are hardly ever simultaneously executed well together, and if this were a run-of-the-mill P&C underwriter, Trupanion’s thin capital base would probably be reason alone to pass.

But I think Trupanion is a different animal. The risks covered under pet medical insurance are bite-sized and absent a major, widespread health contagion, uncorrelated. Agglomerating hundreds of thousands of claims results in a more predictable range of experiences from year-to-year at the population level than most traditional P&C exposures and with far less tail risk too. Given the highly granular, uncorrelated nature of the insured risks, catastrophe is a remote risk. The company’s exposures are also short-tailed, meaning that claims-triggering events are readily apparent and the costs from those events accurately estimable and paid soon thereafter: over 90% of the company’s reserves as of 3q17 are related to activities incurred in 2017 and close to 95% of claims paid over the last year was related to business underwritten in the same year. Only a miniscule amount of claims incurred and paid relate to prior years. [one negative consequence to premiums heading out the door to pay claims almost as soon as they come in is that Trupanion doesn’t benefit from “float” income as a typical insurer does].

Compare this to the “long-tail” risk of asbestos, where the health consequences from exposure remained latent for many years and claims were still being paid more than decade after policies were originally underwritten…that is, people were getting silently screwed by asbestos during the coverage period; the insurance companies didn’t know it at the time and so didn’t properly reserve for it. In contrast, the short-tail nature of Trupanion’s risk means that its best guess about claims cost and frequency is rapidly (in)validated and any deviations can be dynamically accommodated through price adjustments. While Trupanion won’t hike a member’s monthly subscription fee based on her pet’s individual medical condition, it will do so if the average cost of care for all pets within the same sub-category rises, so systematic pricing errors are quickly rectified. Steering the ship is 48-year old founder, CEO, and ~8% owner Darryl Rawlings, who has a good story about how his parents’ experience about not having the money to remedy a life-saving procedure for his childhood dog, prompted him to start Trupanion 10 years later (maybe too good a story?). In any case, I highly recommend reading his annual letters, which are refreshingly exorcised of hygienic corporate bullshit and lay out Trupanion’s operating strategy with a useful degree of granularity. Darryl seems authentically enthusiastic about this pet insurance mission and appears to “get” how value is created…it’s hard to imagine a diversified underwriter/bank/savings institution like Nationwide pursuing this opportunity with the same single-minded vigor.