Looking at TRUP is like staring at one of those ambiguous images that could be both a rabbit and a duck, both a saxophonist and a woman’s face: we know that this is an insurance company, but we’re compelled to analyze it as a data-driven subscription service.

Of course, all responsible insurers are data-driven and the recurring nature of premiums also make them subscription-like, but we don’t typically think of insurers as a subscription service in the same vein as a SaaS enterprise. We do for TRUP largely because its management team has diligently trained us to focus on SaaSy metrics. Some of this is just reframing vocabulary: “subscription fees” not “premiums”, “members” not “policyholders”, “Territory Partners” not “agents”.. Trupanion’s ignorance of the insurance industry lexicon – scarcely a mention of reserves, underwriting leverage, medical cost trends, book value – is so obtrusive as to almost certainly be by design (what fast-growing enterprise wants to be seen as a boring insurance company?).

But this is also the first insurer I’ve see that disaggregates retention by member cohort and discloses lifetime value to customer acquisition cost ratios. That’s not a knock on the company. The first principle to any recurring, subscription-like model, insurance company or not, is onboarding customers for far less money than those customers will generate in lifetime profits. With most of the stuff you buy – a haircut, an iPhone – there is little confusion about the value of the product to you. Insurance is a lot squishier because you don’t know at the time of purchase whether you’ll need it. For major categories of insurance – where the covered thing is monetarily significant and its cost readily determinable, as in the case of a car or house, or where it transcends monetary value, as in the case of your family’s health – we easily buy into the collective understanding that in any given year, the premiums from those on whom fortune smiles subsidize those on whom she frowns. We don’t feel like our rights are being trammeled when law mandates we buy such insurance or that we’re being bamboozled when our insurer earns an underwriting profit from this scheme. We’re risk averse and understand that peace of mind is worth paying for and that an insurer should be compensated for giving it to us. But dogs and cats?

While there’s no question that we treat our pets far more humanely than we used to and that pets have graduated from the status of mere property, they still don’t occupy the same sanctified hemisphere as humans and we’re far from consensus on the range of seriously unfortunate health outcomes that we should be willing to prepare for. If you ask your friends about pet medical insurance, as I did, you’ll likely find that only a few have it, maybe half think it a reasonable purchase and the rest may outright scoff. Rather than pay $50 for a Trupanion policy with a 10% deductible, why not just put $40 in the cookie car every month as a sort of pet health savings account? If I’m shelling out $600 this year for a Trupanion policy and eat 10% of the costs, I need to think there’s a 20% chance of at least $6,000 in medical emergencies in the next 12 months for the policy to be “worth it”. [to put that in context, treating hip dysplasia for a Golden Retriever can cost anywhere between $2,000 (if diagnosed early) and $5,000 (if diagnosed late and a hip replacement is required)].

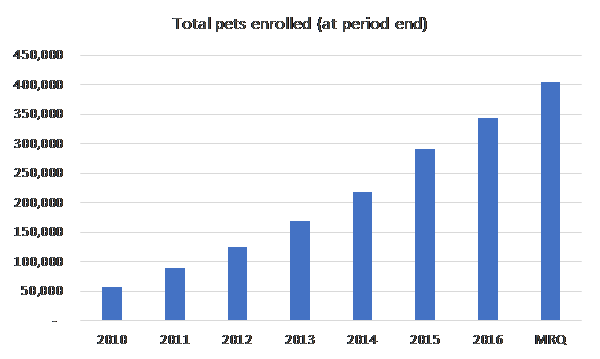

Of course, the decision to purchase insurance can be an emotional one that goes beyond sterile expected value calculations, and the more importance you place on your pet’s life and comfort, the less willing you are to roll the dice…but the point is that on the surface, it’s not entirely clear to me pet owners feel they need insurance for their pets. But can they be made to think they need it? There’s some evidence to believe that they can: the number of pets covered by Trupanion has compounded by 25%/year since 2011 to over ~360k and nearly 85% of members renew their policies every year…and half the lost profits of those who don’t renew are offset by existing members who insure more pets or refer their friends. The proselytizing efforts begin with the 40,000+ vets staffed at the 28,000 vet hospitals across North America (20,000 of which are independently owned and operated) who deliver ~54% of TRUP’s new members and from whom pet owners seek trustworthy guidance. [According this recent Motley Fool interview [1], Trupanion’s CEO claims that when vets recommend Trupanion to their clients, 1 in 4 people enroll.]

Sometimes oblique coverage restrictions, annual payout caps and long waiting periods for covered treatments are buried in fine print; other times, the insurance company and the vet charge based off different fee schedules, with the pet owner paying for the entire procedure out-of-pocket based the vet’s fee schedule only to be reimbursed weeks later by the insurance company using a lower “usual and customary” rate [which is based on fees charged by other physicians in the surrounding area for the same procedure]. A vet probably won’t be blamed for not proactively recommending pet medical insurance, but pushing a policy that culminates in an expensive “gotcha” moment is poison. Trupanion attacks these causes of friction and confusion by:

1/ pricing off the cost of care. Trupanion carefully estimates the cost of medical care across 1mn+ dimensions – species, breed, zip code, deductible, age – and simply tacks on 30% to arrive at the policy price paid by the pet owner…so, a pet owner is basically paying a 30% premium above expected medical costs to rid herself of cost uncertainty. Trupanion then pays out 90% of the vet’s invoice, with no limits per claim or illness. So, it doesn’t matter if one vet charges $2,000 and a rival vet across the street charges $1,000; Trupanion will cover 90% of the eligible treatment cost in both cases. Assuming Trupanion has accurately estimated the cost of care, in aggregate, 70c of every premium dollar Trupanion collects goes to paying vet invoices;

and

2/ re-directing reimbursement flow (in progress). With traditional pet insurance, the patient covers the entire vet invoice upfront and then hopes the check that arrives from the insurer in 2 weeks will reimburse her for the “right” amount. While most of Trupanion’s claims are still paid via check, they are increasingly routed through Trupanion Express, in which Trupanion pays the vet 90% of the bill directly, thereby taking the burden of up-front payment away from the consumer. Express can be integrated into practice management software so that an invoice is immediately shot over to Trupanion, who wires the requested funds into the vet’s bank account in less than 5 minutes. The number of vet hospitals with Express installed has grown from 89 in mid-2014 to 500 in 2015 to ~1,300 today, with over 30% of vet invoice dollars channeled through Express, on its way to 95%+. No other competitor in the space is even bothering to pursue a similar direct payment scheme.

These two changes largely lift the confusion attending discrepant pricing schedules and alleviate the strain of what in some cases could be an enormous immediate upfront payment for the pet owner, followed by an anxiety-ridden reimbursement interval. The member knows his out-of-pocket burden from the get-go and will not be financially surprised down the line. And because a Trupanion member need not wrestle with the financial uncertainty of costly medical care, she spends twice as much on vet services over her pet’s life than an uninsured pet owner…and the vet can simply focus on recommending the best treatment, without also stressing over the owner’s ability to pay.

Even so, considering the history of disappointing experiences with pet medical insurance, it’s no wonder that winning over vets has proven a laborious process. It can take 3-5 visits for a Territory Rep to even get her first meeting…so, if the TR is making 1 visit every 6 months, we’re talking years. Trupanion makes close to 100,000 face-to-face vet visits every year, with 200 hospitals per territory visited every 60 days (with touch frequency now increasing with impending account manager build out), and even after hammering away at vet conversion for nearly a decade in the US, the company still has significant work ahead: against a universe of 25,000 addressable hospitals in the US, only 8,100 are actively recommending Trupanion today, a figure that is growing by ~500-600 hospitals/year. Competitors, on the other hand, continue to take a direct-to-consumer approach, carpet bombing their territories with online marketing to create awareness, which in the absence of vet buy-in has not proven very effective.

Building trust is a time consuming process that requires TRs to persistently contact vets, who must then observe positive customer experiences firsthand. These relationships cannot be bought, but must be earned over time: a vet hospital will not compromise a pet owner’s continuing business for referral fees and besides, Trupanion does not offer kickbacks of any kind to vets for referring patients. You may be surprised to know that with the exception of VPI Nationwide, the largest player in the space with 40% share (vs. #2 Trupanion with 20%), other competitors like Healthy Paws and Pet Plan don’t underwrite the policies they sell. Trupanion’s conceit is that by owning all links in the chain – from sales to underwriting to claims processing to customer service – and forgoing reinsurance, it can provide insurance at a ~20% lower cost than peers. These savings are used to cover a greater proportion of claims costs – 70% of premiums at Trupanion vs. closer to 50% for peers – enabling a “no-fuss” payments experience that induces greater satisfaction from pet owners (who remain Trupanion members for longer) and buy-in from vets (who feel comfortable enough to recommend Trupanion to new clients).

Of course, sustainably profiting off a cost-plus model and credibly delivering on the promise to immediately cover 90% of whatever invoice requires precise, granular insight into the cost of pet acquisition and medical care. Over 17 years since inception, with data from 1.5mn+ claims and over 500,000 invoices/year, Trupanion has amassed cost and retention experience across 1mn+ category permutations…so, for instance, the company understands how the claims experience of a 5-year old bulldog in zip code 11201 differs from that of a 3-year old Shih Tzu in 60047 and can price the two pets accordingly. There are no short cuts to this process. The time required to build claims experience and flesh out statistically significant patterns at such a granular level is a steep learning curve that even a well-funded competitor cannot easily surmount. Although VPI Nationwide has been around longer than Trupanion, their dataset is less robust because they don’t price their policies with nearly as many observations (zip code, for instance) as Trupanion, nor do they cover congenital and hereditary conditions. [to be clear, Trupanion doesn’t cover pre-existing conditions either, but unlike other insurers, it doesn’t refuse coverage on all future illnesses arising because of pre-existing conditions].

Still, while data may be a competitive advantage in the early stages of penetrating a market niche, I’m not sure this in itself constitutes a real moat. Data has to be proprietary, valuable, and part of a self-reinforcing process (data network effects) for it to count as a sustainable edge. There’s a reason why you never hear insurers tout data as a unique advantage…there are diminishing returns to data as the relationship between price and insured risk doesn’t change all that much for granular exposures and eventually becomes common knowledge.

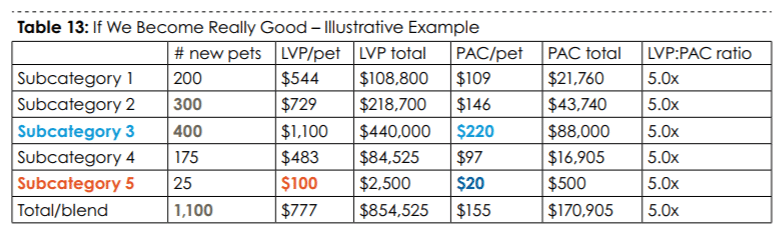

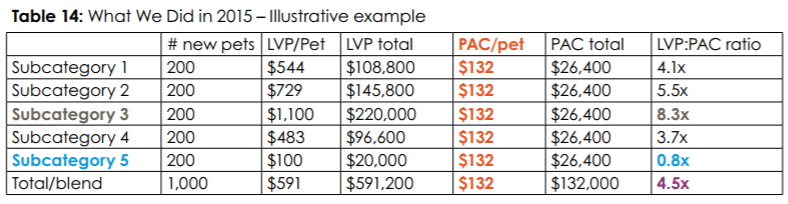

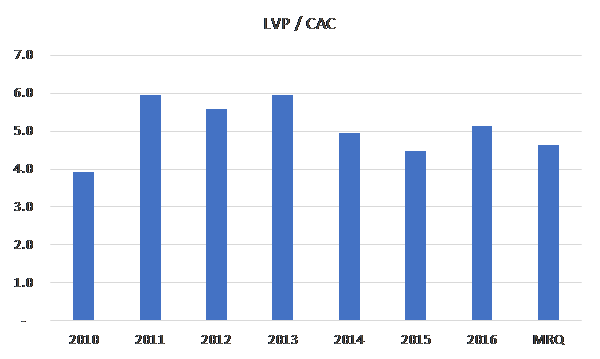

(the Lifetime Value of a Pet (LVP) to Pet Acquisition Cost (PAC) ratio that Trupanion reports every quarter is the blended output of explicit LVP:PAC targets across a slew of subcategories. So, while the lifetime value of, say, a 2-year old cat in Manhattan with a $1,000 deductible will differ from bulldog puppy in Pittsburgh with no deductible, Trupanion can toggle pricing and acquisition spend to get iteratively closer to a common IRR across subcategories, with no cross-subsidization between them. Ideally, the table would look something like this…

Not. quite. there. yet…

…

(Tables 13 & 14 from Trupanion’s 2016 Annual Letter)]

Meager pet insurance adoption rate in North America (< 2% of ~180mn dogs and cats) compared to certain Western European countries (25% in the UK, 50% in Sweden), is an oft-touted part of the bull case. Of course, one wonders why, when pet insurance has been available in America since at least the mid-80s, the disparity exists in the first place? I don’t really know. But one reasonable-sounding explanation I’ve heard is that in Western Europe, pet insurers launched by first winning over vets and those vets then pushed the product to consumers…whereas in the US, insurers started by asking “what price will pet owners pay for this thing called ‘pet insurance’?” and then reverse engineered a product without consulting the vets, yielding something that both consumers and vets hated.

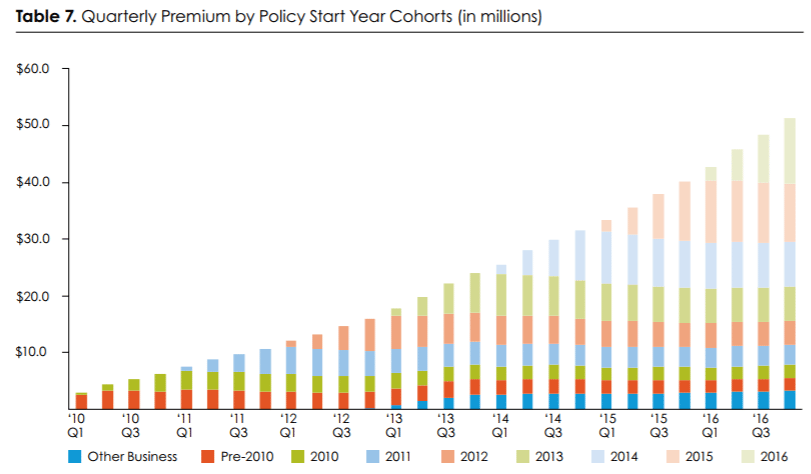

In any case, it doesn’t really matter. I think we just want to see that the method to driving category adoption is sound. In an embryonic market, it’s up to pioneering companies to create the category. Pet medical insurance is so nascent in the US that although Trupanion continues to claim share – there are around 20 brands that make up the pet insurance space, but 2 players, VPI Nationwide and Trupanion, account for 60% of the insured pets – it does so in a market that, against the broader population of insurable pets, barely exists. Rather than look to foreign countries for cues, it seems better to just make a judgment call on whether a) the value proposition for vets makes sense, b) the company has the will and wherewithal to push the ball forward, and c) the product, when discovered and used by the end consumer, solves a real need (including a need the consumer previously didn’t even know she had). a) and c) are tied at the hip since, as previously discussed, vets will only pitch Trupanion if the pet owner perceives benefit. While I harbor doubts about the intrinsic value to a pet owner, those personal reservations are trumped by nearly a decade of data strongly supporting the claim that yes, pet insurance is becoming a thing in the US. As born out over many cohorts, the average life of a Trupanion member is around 6 years…

…during which period the company pulls 20c in variable profit from every incremental premium dollar, reinvesting most of that into acquiring new pets…

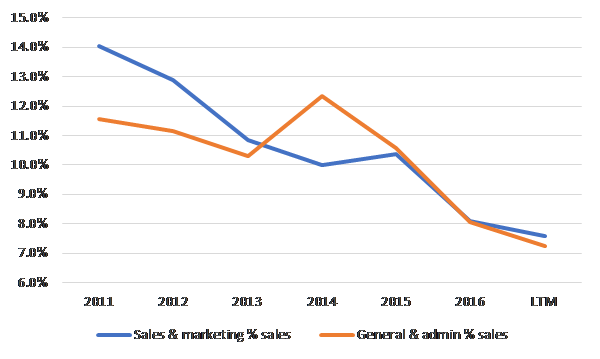

….at compelling lifetime values translating into huge IRRs, leveraging sales & marketing and fixed expenses along the way.

The IRR math works roughly as follows: on average, Trupanion pays $175 to acquire a pet and recognizes premiums of around $53 for that pet each month over 71 months. That 53 bucks is whittled away like so:

Monthly premium: $53

Vet invoices: ($37) [70% of the $50 premium]

Variable expenses: ($5)

Contribution profit: $11 [20% of premiums. The Lifetime Value of a Pet (LVP) is computed off this figure]

After adding back sales & marketing, Trupanion’s trailing 12 month EBITDA margin after stock-comp is ~8%, implying fixed costs of ~12% of premiums [20% contribution margins less 8% EBITDA margins ex. sales and marketing], so 60% of contribution profits are being consumed by fixed operating costs at the moment.

But at scale, which management pegs at ~700k pets (vs. over 360k today growing low/mid-teens y/y), the company thinks it can do 15% adjusted operating margins excluding the cost of adding new pets. When we back off 1%-2% for stock comp, it’s maybe more like 13%. Given the degree to which Trupanion has leveraged its cost structure over the last 6-7 years, I find this claim credible.

And so, at scale…. .

Fixed expenses: ($3)

Capital charge: ($0.6) [8% x (monthly premium divided into a premium:surplus ratio of 6x)]

Profit/pet/month: $7 [13% of premiums]

In other words, the company is generating ~$520 in profits over the average lifetime of a member, around 3x the cost to acquire that member. The cash flow streams over ~71 months impute a 65% IRR. Alternatively, at a 15% discount rate, the present value of cash flows over of a subscriber’s life is ~$330, nearly twice the cost of acquisition. Imputing attractive unit economics, of course, requires a sufficiently wide LVP-PAC spread. The $175 pet acquisition cost that I am using assumes the current LVP/CAC of 4.5x, where it has roughly been for the last 5-6 years. This figure would have to decay to below 2.5x before the NPV of pet acquisitions turns negative (i.e. destroys value).

But I see no reason to expect such a draconian deterioration and in fact, it’s possible that as the company further densifies its markets with vet allies, layering on radio and TV spend may even boost conversion from vet recommendations, as has been true thus far in Trupanion’s mature markets where half or more of vet hospitals actively recommend Trupanion.

Given the unit economics and the runway, it’s not hard to see how things can get interesting [though whether they can get interesting enough to buy the stock at today’s valuation is an entirely different question]. Assuming today’s annual PAC spending of ~$15mn/year grows by a few million per year and even assuming LTV/CAC deflates to below 4x, I can get to just over 800k enrolled pets in year-7, around 12% growth per annum. Absent some “silver bullet for cost effective accelerated organic growth” (company’s words), management seems determined to fund its expansion entirely with internally generated profits.

Applying a pre-PAC scale margin of 13% to implied revenue gets us to around $70mn in pro-forma EBITDA, which, assuming reinvestment, will be growing by low-teens, providing still more ammo for pet acquisition. With 800k enrolled pets against a universe of 180mn dogs and cats in North America, Trupanion will still not have even nicked the surface of its potential…so, still be plenty of opportunity to deploy maybe 40%-50% of pre-PAC EBITDA into onboarding pets at 40%+ IRRs. In theory at least. What you’ve just seen is the rabbit. But what about the duck?

After all, this is still an insurance company and balance sheet strength reigns paramount. But is it and does it? Trupanion’s underwriting leverage – premiums to surplus ratio, a measure of how much underwriting risk you are assuming relative to the capital you hold – is greater than 6x [Trupanion does not reinsure its risk, so subscriptions = gross premiums = net premiums]. Whether this exceeds the standard of prudence depends on the nature of risk being insured. Typically, a ratio greater than 3x is considered unusually aggressive for a P&C underwriter and an insurer with significant high-severity natural catastrophe exposure will keep it closer to 1x. Health insurers, in contrast, will underwrite 7x+ their surplus. In my experience, growth and conservative underwriting are hardly ever simultaneously executed well together, and if this were a run-of-the-mill P&C underwriter, Trupanion’s thin capital base would probably be reason alone to pass.

But I think Trupanion is a different animal. The risks covered under pet medical insurance are bite-sized and absent a major, widespread health contagion, uncorrelated. Agglomerating hundreds of thousands of claims results in a more predictable range of experiences from year-to-year at the population level than most traditional P&C exposures and with far less tail risk too. Given the highly granular, uncorrelated nature of the insured risks, catastrophe is a remote risk. The company’s exposures are also short-tailed, meaning that claims-triggering events are readily apparent and the costs from those events accurately estimable and paid soon thereafter: over 90% of the company’s reserves as of 3q17 are related to activities incurred in 2017 and close to 95% of claims paid over the last year was related to business underwritten in the same year. Only a miniscule amount of claims incurred and paid relate to prior years. [one negative consequence to premiums heading out the door to pay claims almost as soon as they come in is that Trupanion doesn’t benefit from “float” income as a typical insurer does].

Compare this to the “long-tail” risk of asbestos, where the health consequences from exposure remained latent for many years and claims were still being paid more than decade after policies were originally underwritten…that is, people were getting silently screwed by asbestos during the coverage period; the insurance companies didn’t know it at the time and so didn’t properly reserve for it. In contrast, the short-tail nature of Trupanion’s risk means that its best guess about claims cost and frequency is rapidly (in)validated and any deviations can be dynamically accommodated through price adjustments. While Trupanion won’t hike a member’s monthly subscription fee based on her pet’s individual medical condition, it will do so if the average cost of care for all pets within the same sub-category rises, so systematic pricing errors are quickly rectified. Steering the ship is 48-year old founder, CEO, and ~8% owner Darryl Rawlings, who has a good story about how his parents’ experience about not having the money to remedy a life-saving procedure for his childhood dog, prompted him to start Trupanion 10 years later (maybe too good a story?). In any case, I highly recommend reading his annual letters, which are refreshingly exorcised of hygienic corporate bullshit and lay out Trupanion’s operating strategy with a useful degree of granularity. Darryl seems authentically enthusiastic about this pet insurance mission and appears to “get” how value is created…it’s hard to imagine a diversified underwriter/bank/savings institution like Nationwide pursuing this opportunity with the same single-minded vigor.