I.

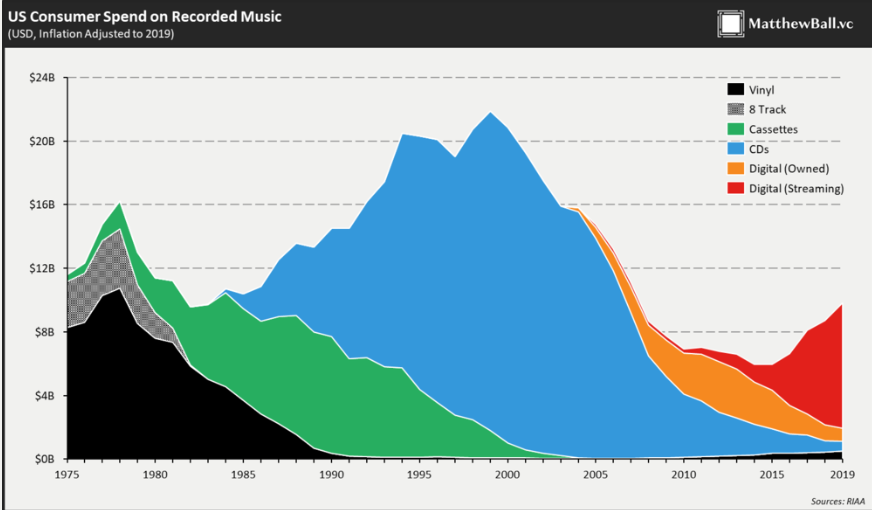

Every few years, this graphic from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), reproduced by Matthew Ball, makes the rounds:

It shows how a 15-year decline in recorded music revenue, precipitated by the cannibalistic effect of free downloads, is being reversed by the rise of subscription fees from digital streaming providers (DSPs). As I detailed in my Spotify/Sirius post [1] from 3 years ago:

See that peak in the chart of recorded music sales below? That’s what it looks like when an oligopoly controls the point of scarcity and bundles tracks together in an album, forcing consumers to pay for the songs they don’t want in order to get the songs that they do. This gave way to a period where tracks were disaggregated from CDs, encoded into mp3’s, and distributed for free on file sharing services like Napster. Given how profitable CD albums were, you will not be surprised to learn that the labels summarily rejected the opportunity to license copy-resistant mp3 technology years before Napster was launched (and then they later refused to partner with Napster). And you’ll notice in the above exhibit that during the 2-to-3 year period after Napster launched but before the ubiquity of portable players allowed consumers to carry mp3s with them, Napster may have actually facilitated discovery and boosted CD sales. But the portable players caught up and the labels, whose production and distribution efficiencies were constrained by the limits of the physical world, proved no match for the network effects and the zero marginal distribution costs of Napster’s P2P model.

Harrowing declines in album sales finally forced the record labels to unbundle CDs. Through iTunes, they offered individual tracks, which hewed more closely to consumer needs than albums but still did not capture variations in a song’s long-term appeal since every track was priced at 99c regardless of how many times it was subsequently played. Per-stream pricing, where the artist/label is paid every time her song is played, is now supplanting owned tracks. Each transition, from album to owned track to streaming, more closely aligns payment with song popularity.

By consolidating and curating the world’s music, Spotify did what record label lawyers and the US court system never could: they made music worth paying for again. For a growing number of consumers, subscribing to Spotify for ~$10/month provided more value than pirating tracks for free. A minor contribution 10 years ago, digital – which includes payments from DSPs like Spotify as well as emerging platforms like TikTok and Roblox – now accounts for between ~60% and 70% of Universal, Sony, and Warner’s recorded music revenue.

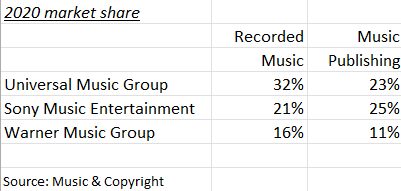

But while the way music is consumed has transformed over the last 10 years, industry profits are still largely captured by the big 3, who following their acquisitions of Polygram, BMG, and EMI, now command nearly 70% and 60% of recorded music and music publishing revenue, respectively:

The incumbents may trade a few points of share from one year to next depending on which artist is topping the charts. Also, independent labels are chipping away at the periphery (more on this). But for the most part the industry operates as a stable oligopoly.

II.

Every music recording carries two separate ownership rights: one covering an artist’s original recording (“Masters”) which falls under the labels’ recorded music segment; the other protecting the songwriting (lyrics and musical composition), which falls under publishing.

The recorded music segment, which comprises around 83% of Universal and Warner’s profits, is in the business of discovering and signing artists who they hope will grow into mega stars like Drake and Taylor Swift. They front capital (”advances”) to promising artists and remit anywhere between 15% and 25%+ of revenue (”royalties”)1 [2] to them, with the high end of that range reserved for stars with bargaining power. Royalties are recoupable, meaning that they are paid to the artist only after the record company has recouped its advance.

Just making up numbers here, let’s say Spotify does $1bn of subscription revenue this month. Around 52% of that ($520mn) goes to a royalty pot reserved for Masters rightsholders (the record labels). Assuming Universal accounts for 30% of Spotify streams2 [3], they are entitled to 30% of the pot (30% x $520mn = $156mn)3 [4].

A top-tier artist who makes up, say, 5% of Universal’s steams on Spotify, will have $7.8mn (5% x $156mn) allocated to its Masters. At a 20% royalty rate, the artist earns $1.6mn (20% x $7.8mn). For CDs and digital downloads, the 20% royalty is applied to the wholesale price of every album sold, so if 200k CDs are sold at a wholesale price of $7, the artist will earn $280k (20% x $7 x 200k). Artists also share in the payments Universal gets for songs played by non-interactive streaming programmers (like Pandora and iHeart Radio, who choose the songs their user hears) and satellite radio providers (Sirius XM) – where rates are set by law and royalties are collected and paid by SoundExchange, a non-profit rights management organization – not to mention TV shows, commercials, motion pictures, and “emerging” platforms like TikTok, YouTube, Roblox, Peloton, etc., which we’ll ignore here4 [5].

The artist doesn’t actually receive any of the royalties she earns until Universal has recouped not only its advance but also the cost of recording, ad campaigns, tour equipment, etc., some of which can be negotiated depending on the importance of the artist (most recording contracts today are structured as “funds”, where the artist receives an advance plus a fixed sum to cover recording costs). So assuming a $3mn advance, the artist will still be unrecouped by $1.2mn ($3mn – $280k – $1.6mn) in the above example.

Some analogize record advances to loans, but that’s not exactly right since if the artist flops they are under no obligation to repay. And in fact, failure is the norm. The vast majority of artists do not recoup their advance. That a handful of successful artists compensate for the failure of many many others is sometimes why the artist & repertoire (A&R) business (that is, the business of finding and developing talent) is sometimes compared to venture capital. And like sophisticated venture capitalists, the major record labels are extremely savvy about contract language and have over generations conjured all sorts of ways to minimize risk. Among other measures, most contracts contain cross-collateralization provisions, which means any royalties earned on your second album will first go towards covering deficits on the first, and so on. They also impose a ceiling on advances for subsequent albums5 [6] and diversify revenue streams through 360 deals that take a cut on gross proceeds the artist realizes from acting, touring, sponsorships, and other activities. Furthermore, traditional record deals stipulate that after committing to 1 or 2 albums, the label is granted options for another 4 or 5, so they can exercise each incremental option while the artist is hot and cut bait otherwise.

In staking risk capital to develop artists, record labels have decade+ rights to or outright own the Masters, entitling them to long-term annuity-like earnings streams. It’s unlikely that a label generates much of a return in the initial 2-3 year frontline window, where the label is spending significant resources to break a new artist. After that initial investment period, however, when the track moves into catalog, a recorded track’s cash flows can be milked with very little incremental promotion (Sony isn’t putting nearly the same amount of money promoting the Beatles as they are a newer artist). You might think of frontline A&R as a low-margin feeder into catalog, where the real money is made. Catalog music makes up maybe 50% of a major label’s revenue but 70% of its profits6 [7]. Universal reported that catalog (3+ years) contributed 58% of its digital and physical recording revenue last year. Not only do the catalogs of major labels make up the bulk of recording profits, they represent a key source of power. According to MRC data from Billboard [8], catalog (18+ months) music accounted for 75% of music consumption in 2021, up from 66% in 2020. The vast majority is owned by Universal, Sony, and Warner. A music steaming service doesn’t work without catalogs from all three.

The other meaningful business segment for the major labels, comprising around ~16% of segment profits, is publishing. A publisher is to songwriters what a record label is to artists: they license song compositions and lyrics to programmers and share the resulting revenue. So when Spotify streams a song, they pay two sets of royalties that sum to around 70% of subscription revenue: one to the recording rights owner, who gets ~52%, and another to publishers and songwriters, who together take another ~15%. Unlike the recorded music segment, which lays out VC-style risk capital to popularize artists, publishers are tasked with the safer, less capital intensive role of administering song copyrights (securing licenses, collecting money, and paying writers). Their cash flows largely piggyback on the investment put in by record labels.

And whereas record labels strike direct bespoke agreements with each programmer that are re-negotiated every 2-3 years, the royalty rates earned by publishers and songwriters are for the most part mandated by statute. That’s because song reproductions in physical and digital formats are covered by a compulsory mechanical license7 [9], meaning that under the Copyright Act the rights owner must license the song to anyone who wants it. In addition to mechanical licenses, songs are also protected by public performance rights, meaning any radio station, streaming service, nightclub, etc. that plays a song needs the rightsholder’s permission, which they obtain through a blanket license administered by Performing Rights Societies (aka “Performing Rights Organizations”), who keep track of all the places the music is played using methods that we don’t need to get into here.

In the US, the 3 major PROs are ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC. Publishers will license all their songs to these entities, who turn around and license the songs of all the publishers they represent to users (streaming services, radio stations, etc.) in exchange for a fixed fee that can vary from hundreds of dollars to millions depending on the size of that user’s audience. After subtracting their operating expenses, PROs distribute half the remaining funds to writers (the “writer’s share”) and the other half to publishers (”publisher’s share”). Typically, the publisher will then pay half their share to the songwriter, who thereby ultimately ends up with 75% of the total PRO distributions (50% + 1/2 x 50%)8 [10]. Mechanical licenses are issued in the US by the Harry Fox Agency, who takes 11.5% of the associated fees it collects (though some larger publishers, enabled by technology that makes it easier to administer licenses, are reaching deals directly with licensees). HFA passes these fees to the publisher, who in turn passes half to the songwriter.

(you might wonder whether streams and digital downloads, which can be categorized as either public performances or song reproductions, are governed by mechanical or performance licenses, which impacts how artists are paid. In many European countries, downloads are 25/75 performance/mechanical and interactive streaming is 75/25; in the US, interactive streaming is mechanical but the publisher is paid under a complex formula whereby the DSP pays 15% of subscription revenue (a rate set by the Copyright Royalty Board), part of which is allocated to the performance license fee (for reporting purposes, Universal and Warner break out “digital” as a line item that is separate from mechanical, which for reporting purposes only covers only physical media).)

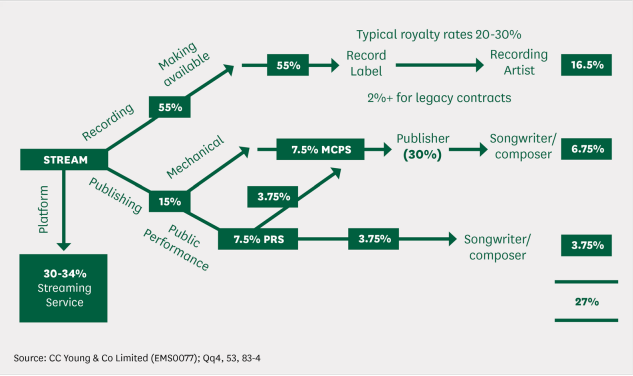

The labyrinthine division of a DSP subscription dollar is summarized below (the percentages below apply to the UK and differ somewhat from the US-biased percentages I used in my examples above):

Using my numbers, it looks like a dollar of subscription revenue realized by an interactive DSP roughly breaks down like this:

Record Label: 44c

Publisher: 6c

DSP: 33c

Artist: 8c

Songwriter(s): 8c

(the numbers don’t add up to $1 due to leakage from PRO and HFA fees)

So around half of every streaming dollar is paid to recording and publishing rightsholders who, in the case of the 3 majors, are housed under the same roof.

Note how the flow of funds in publishing differs from recording. Whereas in recording the labels collect all the money from the DSP and distribute royalties to artists, in publishing the money is intermediated by third parties, with the exception of songs used in TV shows, movies, and commercials, which are covered by direct synchronization (or “sync”) licenses between publisher and programmer.

(before I get “ackshually”-ied, let me state the obvious: for the sake of simplicity, I’m skipping over lots of contingencies and nuances. Revenue share differs by media and geography, and the bargaining power of the various parties involved can alter the distribution of earnings rather significantly. If you are interested in the gritty details, I highly recommend reading Donald Passman’s All You Need to Know About The Music Business, which is where I pulled many of my numbers.)

III.

The bull case for Universal and Warner is easy enough to understand. They own or license exclusive rights to a pool of IP whose value continues to appreciate in value as its presence in our lives becomes ever more ubiquitous. With recorded music consumption shifting from physical sales and downloads to digital streams, music is being monetized as predictable and recurring revenue rather than as one-off sales, in much the same way enterprise software is purchased as SaaS subscriptions rather than perpetual licenses. And whereas the SaaS migration came with a gross margin trade-off for software vendors, the transition to digital music delivers a margin lift for the record labels, who no longer bear the costs of manufacturing and distributing CDs.

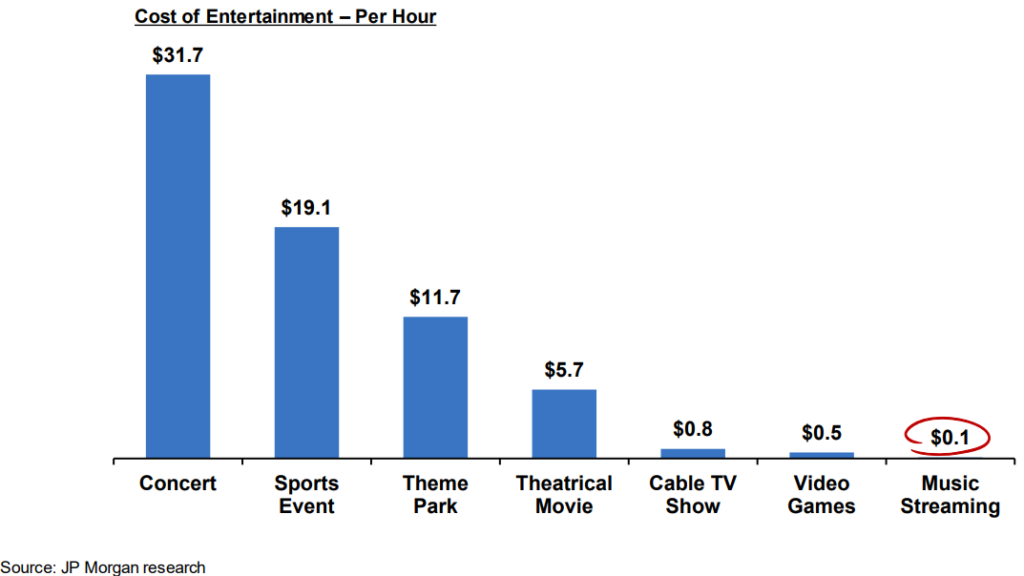

Goldman Sachs sees worldwide streaming subscriptions growing by 10%/year to 1.3bn9 [12]. Pershing Square, who owns 10% of Universal, expects more like 14%. In either case, most of the growth will be fueled by emerging markets (Spotify reports 32% MAU/TAM penetration in established markets compared to just 8% in in emerging), where ARPUs are substantially lower (Spotify’s Premium ARPU has declined by around 6%/year since 2016 due to this mix shift). Some of that dilution should be offset by ARPU gains in developed markets, as music remains very under-monetized compared to other forms of entertainment:

At the 1999 peak of recorded music revenue, the average CD buyer spent around $45 a year on music10 [13], so maybe 30 to 40 songs across 3 CDs? Today, a Spotify subscriber pays less than 3x as much for ~70mn tracks, the same as a Rhapsody subscriber paid for 5mn songs [14] in 2008.

In addition to streaming platforms, music is being woven into all kinds of once inconceivable use cases. In the mid-2000s, the labels were partnering with mobile providers to capitalize on ringtones; today, they supply the background soundtrack to Peloton classes, Roblox scenes, and TikTok challenges. Warner’s revenue from these emerging applications have more than tripled over the last 2 years and account for 7% of its recorded music business. Warner, Sony, and Universal sit are both toll booths sitting between artists and the hundreds of digital platforms through which fans access their music.

The big 3 occupy this privileged position because they control most of the rights to the industry’s catalogs, which comprise nearly 3/4 of US streams. This speaks to a unique property of songs: as 3-5 minute snippets of sound that concurrently augment other activities, they are played over and over again. Movies and TV shows, which require more time and dedicated attention are, on the other hand, typically watched just once or twice. Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music can’t differentiate on unique content the way Netflix, HBO, and Hulu might, nor can they source from a fragmented base of owners. Imagine subscribing to a platform that doesn’t carry Taylor Swift, Drake, or The Beatles. It’s a non-starter. A streaming service that doesn’t license the catalogs of all 3 majors is no streaming service at all.

IV.

So on the surface, Universal and Warner check the classic compounder boxes – they are oligopolists in a growing end market with stable demand, monetizing long duration assets as recurring earnings streams with few reinvestment requirements. But some of the factors that have catalyzed the industry’s renaissance also give rise to new challenges.

With technology and social media making it easier to directly reach fans, bargaining power is shifting from the record labels to artists, who are negotiating higher royalties and advances while reducing the number of optionable albums. The deal used to be that in return for assuming the risk of promoting new talent, record labels could bank on owning recording rights into perpetuity. But it’s become more common for artists to own the recording rights and lease them to record labels, as in the case of agreements struck with Drake, Taylor Swift, and Jorja Smith (as Prince once put it [15], “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you”). In some cases Masters are returning to artists within 10 years. On the publishing side, rather than grant partial control of copyrights to publishers and split the earnings 75/25 under co-publishing agreements, it is becoming more common for songwriters to own the compositions entirely while paying publishers a 10%-15% administrative fee to manage licenses and collect royalties.

To what extent does label sponsorship contribute to stardom? Do record labels turn artists into superstars or do they merely glom rising talent? In the analog days, the answer was cut and dry. Teams of A&R men with honed intuition would scour local clubs and review submissions from managers to discover unknown artists and feed promising talent through labels’ massive distribution machines. As I wrote in my Sirius/Spotify post:

They steered which songs were played in radio stations and controlled distribution by colluding with major retailers like Musicland and Tower Records. In owning production, discovery, and distribution – costly functions that could not be independently undertaken by artists – record labels functioned as kingmakers for a select few, leaving a long tail of artists who toiled in obscurity, with no way of getting their music in front of fans.

But high quality DIY recording tools and free online distribution have obviated some of gatekeeping functions once played by record labels. Billie Eilish and Jorja Smith got their start uploading tracks on SoundCloud. Stormzy came up by posting freestyle raps on YouTube. Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” blew up on TikTok before hitting Billboard charts.

TikTok has blossomed into a major discovery engine. By now we’ve all seen the TikTok of 420doggface208 posted skateboarding with a bottle of Ocean Spray Cran-Raspberry juice in hand, lip-syncing to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams”, a sensational viral moment that catapulted this 1977 hit to the Rolling Stone Top 100 and led to a surge in digital downloads and streams of the song [16]within days of the post. Music Journalist Elias Leight remarked “TikTok is like a machine gun shooting out viral songs even more than daily”. But TikTok’s influence on the music industry goes beyond one-off cultural moments. Here is a 2021 study from Vox [17] that details how TikTok virality can change the long-term trajectory of a musician’s career. Of the 125 unestablished artists who went viral on TikTok after January 202011 [18], 46% went on to sign with a major record label, and of the 367 artists who landed their first record deal, 1/3 cited a viral moment on TikTok as the catalyst.

Nearly every one of the 125 TikTok artists with a viral hit saw a corresponding spike of streams on Spotify (the “TikTok-to-Spotify” pipeline), and almost all then saw their other tracks included on editorial playlists. Of the 332 unestablished artists who made Spotify Top 20 Chart after January 2020, 1/4 caught their big break on TikTok. An artist who goes viral on TikTok is very likely to be approached by every major label, which can lead to a frenzy of bidding activity that results in far more favorable royalty and licensing terms than DIY artists could negotiate 10 years ago. The major labels will insist that their relationships with hundreds digital platforms yield data advantages that can be used to plan tours and guide marketing, but to collect data across online properties they are often relying on third party tools like Chartmetric and Instrumental that are used by other labels and managers. Also, when it comes to discovery I question value of platform relationships as the tracks being discovered originate from viral moments generated by a handful of services – a track goes viral on TikTok before percolating across the hundreds of other DSPs – whose public data everyone more or less has equal access to.

For a flat subscription fee, DistroKid (which raised money at a $1.3bn valuation in Aug 2021), CD Baby, and Believe Digital (slash TuneCore) will distribute across TikTok, YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music, etc.; track streams and downloads; and even collect money for independent artists without taking a cut (CD Baby will even press vinyl records). There are also independent labels who will distribute for a much lower cut of revenue than full service majors while charging separate fees for other services like marketing and promotion. MiDIA Research [19] reports that the major labels continue to lose a bit of share (~30 to 100bps) to independents and self-releasing artists every year. And while the big 3 plus Merlin (who represents hundreds of large independents) still account for 78% of streams on Spotify, this is down from 87% in 2017. Music, like other creative pursuits, has and always will generate a disproportionate share of revenue from a small percent of artists, but the distribution isn’t as skewed as it was in the 1990s12 [20], when literally the only way to get in front of a big audience was to be sponsored by a major label.

I don’t think this is such a big deal though as the incumbents have long operated independent label subsidiaries, with Sony Music’s recent $430mn acquisition of AWAL a salient accent on their long-standing practice of rolling up competitors. Universal, Sony, and Warner are often thought of as monolithic entities, but it’s more accurate to think of them as holding companies for a bunch of genre and region-specific labels. Besides maybe some differences in genre mix and leadership (Universal’s Lucian Grainge is a legendary A&R talent while Warner’s Stephen Cooper is more of a nuts-and-bolts financial guy), they all basically have the same operational setup, compete vigorously for the same artists, and fast follow each others’ strategies.

And for all the anecdata about artists throwing it back in labels’ faces, mega-stars, who you’d think would be in the best position to disintermediate labels, continue to depend on them. Taylor Swift famously re-recorded and released covers of her first 5 albums to devalue her original Masters, which came to be owned by Ithaca Holdings, whose founder/CEO Scoot Braun was publicly called out by Taylor as a “bully”, before being sold to private equity. This re-recording gambit was so successful, with the new covers outperforming the originals, that in recent contracts Universal Music has been “effectively doubling the amount of time that the contracts restrict an artist from rerecording their work [21]”. But though Swift – an 11-time Grammy winning dynamo with 183mn Instagram followers – now owns her Masters, she relies on Universal-owned Republic Records to promote and distribute her work. And after gaining organic traction, Billie Eilish signed with Darkroom/Interscope (owned by Universal), Jorja Smith with Sony/ATV, Lil Nas X with Columbia Records (Sony Music) and Stormzy with Atlantic (Warner Music). I don’t think there is a single top 50 artist that isn’t represented by a major record label, either through long-term licensing terms, during which most of the IP value is extracted, or outright copyright ownership.

I’m reminded of this anecdote relayed by Arman Gokgol-Kline, a partner at Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb in his Business Breakdowns interview [22]:

I spoke to a professor at Berkeley College of Music, which one of creme-de-la-creme music schools in the country, about various aspects of this business. And one of my favorite stories he told me is every year I ask my students to raise their hand when I say to them, “Who likes labels and wants to work with a label?” And nobody raises their hand. And then he says, “Okay, now imagine one of the major labels comes to you and gives you an upfront and wants to sign you. Who would sign on with them?” And everyone raises their hand.

At the end of the day, every musician dreams of stardom and getting there takes more than mere integrations with DSPs. There are 60k tracks uploaded to Spotify every day. How does an artist stand out? The major record labels may no longer have as tight a grip on discovery, but through large advances, promotion, and creative support; relationships with radio stations, movie studios, and global distributors; and the market share to exert soft influence on streaming services to promote their artists, they in a better position than anyone to supercharge talent that has broken out of obscurity. Labels can provide a menu of services tailored to the varying needs of stardom-bound talent, with mid-tier artists availing themselves of short-term distribution deals with independent subsidiaries before then graduating to full record deals as they become more popular.

For the few artists who do manage to become superstars, often the best way to capitalize on popularity is through live concerts. From Business Insider [23]:

Consider, for example, U2 [24], which made $54.4 million and was the highest-paid musical act of the year in 2017, according to Billboard [25]‘s annual Money Makers report. Of their total earnings, about 95%, or $52 million, came from touring, while less than 4% came from streaming and album sales. Garth Brooks (who came in second on the list), owed about 89% of his earnings to touring, while Metallica (ranked third) raked in 71% of their earnings in the same way.

The labels take a healthy cut of streaming revenue but they also raise a superstar’s profile, which helps maximize the value of live appearances.

V.

While record labels are best characterized as service businesses, those services are preceded by up front advances, and the capital requirements have gotten bulkier as competition for publishing catalogs has intensified.

As I mentioned earlier, whereas the revenue split between recorded music rightsholders and the programmers who license those rights are individually negotiated and determined by the relative bargaining power of the two parties, the share of revenue paid by licensees to publishers and songwriters is set by the CRB. While the CRB’s rate rulings can seem unfair to whichever party finds itself on the wrong side of them – to the consternation of DSPs like Spotify, a 2018 CRB ruling raised the payouts on mechanical streaming from 10.5% to 15.1% [26]13 [27] – it seems they also come with concessions so that no side decisively wins. And so, because payout terms are set by law rather than by unpredictable market forces and because cash flows largely ride on the investment that record labels put in to popularize artists, publishing is seen as a very long-lived14 [28] and low-variance annuity.

The last 5 years have seen heightening bidding for song catalogs, with much of this activity fueled by financial buyers. Last October, Blackstone partnered with Hipgnosis Song Management [29] (a music IP investment company), providing $1bn of funds. The same month, Apollo backed HarbourView Equity Partners [30] with $1bn. In February, KKR and Dundee Partners acquired a catalog from Kobalt Capital (which includes songs from the Weeknd and Lorde, among others) for $1.1bn and securitized the portfolio of rights. Last June, Oaktree Capital invested $375mn [31] in independent publisher Primary Wave. A few months after acquiring a majority stake in the publishing and recorded music rights of OneRepublic and the band’s lead vocalist and songwriter Ryan Tedder, valued at $200mn, KKR announced a joint venture with former portfolio company BMG [32], which has since acquired more than 250k copyrights from more than 1k artists and songwriters, including Billy Idol and ZZ Top. This JV is similar to a partnership that Providence Equity Partners struck with Warner Music in 2019.

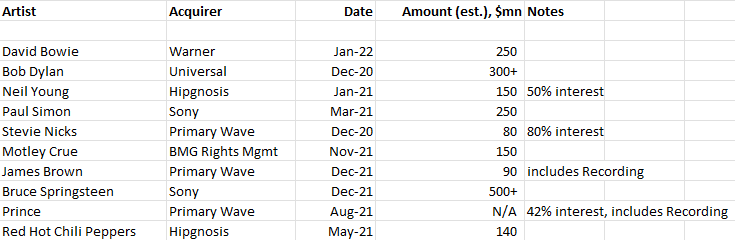

Here is a sample of some notable catalog acquisitions over the last 1.5 years, some of which include other IP rights besides:

(The Wall Street Journal estimates [33]the value of Prince’s estate to be between $100mn and $300mn)

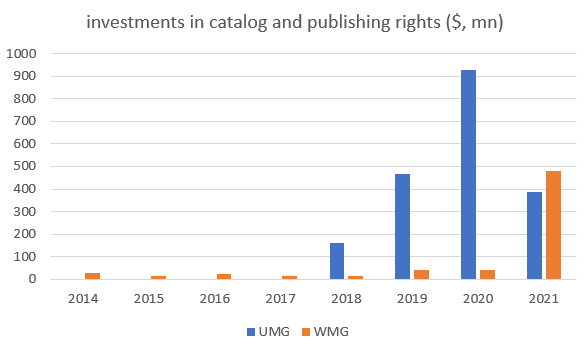

Since its 2018 IPO, Hipgnosis has spent $2bn on IP rights. Warner and Universal have followed suit, investing more in catalogs than they have in years:

(Warner’s fiscal year ends September)

All this frenzied biding has driven deal multiples from a historic valuation of 8x-12x net publisher’s share [34](revenue minus royalties paid to songwriters) to 25x-30x, raising understandable bubble concerns. The enthusiasm is especially concerning to investors because this is the entertainment industry, where creative egos loom large and vanity and empire building often trump financial considerations. On earnings calls and annual reports, Universal and Warner will, with puffed chests, brag about the marquee catalogs they’ve acquired and how many of Top 10 artists they represent (Warner Music has none of the Billboard top 10; they’re doing just fine), while offering no details whatsoever on deal terms or the returns they expect to earn on those investments. With more market share, labels can exert influence on streaming platforms and perhaps also signal credibility to new promising talent – “if a 360 deal with Universal is good enough for Drake, it’s good enough for me” – but separate from those commercial factors, it also confers bragging rights.

A more charitable take on this phenomenon is that the economics of streaming make up for higher deal multiples. I mean, sure, 10-15 years ago catalogs were being sold at 10x, but with the industry crushed by piracy and no proven business model in sight, their earnings streams were also subject to a lot more risk. Moreover, in the 2000 peak, nearly all recorded music revenue came from CDs that were sold in stores, whose shelves could not accommodate a popular artist from 20 years ago. In the streaming era, all the music is available all the time, so one might argue that the useful life of content is longer than it used to be and, when paired with a user-generated content engine like TikTok, is also more discoverable. 420doggface208 skateboards to “Dreams” and a rock band from the ‘70s is resuscitated back into relevance.

Also, the major labels can do more with publishing assets than private equity can. When financial players buy music catalogs, most of the time they are just interested in passively milking bond-like cash flows and levering them up to hit return bogeys. They might do a somewhat better job administering publishing assets better than the previous owner, but I doubt there’s much incremental return from that. Universal, Sony, and Warner, on the other hand, are operators who often own or license the rights to both the publishing catalog and catalog’s associated recordings, which gives them more flexibility to grow and maintain song catalogs by pursuing sync deals with movie studios and licensing arrangements with fitness, gaming and social media apps, or creating biopics, music films (like Rocketman and Bohemian Rhapsody), remixes, and other derivative fare, all of which requires the okay of both the recording and publishing rightsholders. So although they are paying double or triple what they used to for catalogs and accepting somewhat worse commercial terms from artists, the labels might still nonetheless realize more value on a risk adjusted basis than they did in the past. I don’t know that that’s true, but it seems plausible?

I’m eyeballing things a bit as disclosure isn’t great, but the returns on content (EBITA / gross content assets) in Warner and Universal’s publishing businesses look close to respectable at around 9% to 12%. The recording side, comprising over 80% of profits for both companies, has enjoyed phenomenal returns – Warner’s recording segment assets have grown ~$700mn from fy16 to fy20 while EBITA is up ~$500mn; Universal’s recording content assets + goodwill have grown by €1.3bn from 2018 to 2021 while EBITA is up maybe €700mn over that time – which makes sense given the streaming tailwinds and the fact that the majority of recording profits come from catalogs that don’t require much incremental investment.

The management teams at Universal and Warner pinky swear that they’re focused on returns and now both companies have public investors holding them to that promise. Their business models seem to be less about high variance artist discovery and development than about making more assured, educated financial bets on things that seem to be working, whether that means signing record deals with breakout TikTok sensations or acquiring song catalogs with demonstrated longevity. The increasing speed with which tracks mushroom into popularity (”TikTok-to-Spotify” pipeline) may accelerate the recoupment of advances and improve IRRs. Anecdotal concerns that artist royalties are growing more generous and that whatever cost savings realized in the shift from physical to digital will be offset by higher promotion costs aren’t apparent in the numbers – as a % of recording revenue, Warner’s A&R costs have declined since fy16. Warner and Universal have enjoyed consistent EBITDA margin expansion in recent years.15 [35]

But what about the next 5 or 10 years? That the pool of recorded music revenue will continue to expand as music pervades more digital experiences seems like a pretty safe bet, but an industry structure characterized by concentrated pockets of power in different parts of the value chain – superstar artists, record labels, and digital steamers – puts some checks on surplus accrual. The degree to which new modes of discovery and consumption have neutralized the value proposition of the major labels and the power they wield in the music ecosystem, has up to now been more than offset by the radical turnaround in industry prospects that those modes have enabled. I don’t think the big 3 face material existential risk, as they effectively control the key ingredients to every viable streaming service and signing with them is still the best way for a superstar to reach the widest audience. Still, it wouldn’t surprise me to see the combined squeeze of higher artist royalties, a mix shift from full service to modular arrangements, and unfavorable commercial agreements with Spotify hinder margin expansion plans.

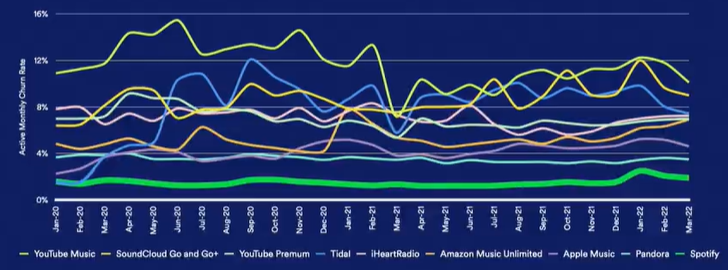

Remember when Spotify bulls looked to Netflix as an aspirational comp? By paying fixed sums for content, Netflix could drop most of the incremental revenue to EBITDA and wouldn’t it be great if Spotify could do that too instead of passing 70c of every subscription dollar to rights owners. But one of the downsides to video streaming is that it requires differentiated content, which puts streamers on a never-ending spend treadmill to retain existing subs and acquire new ones. In music, because every streaming platform must license all the songs from all the majors to be even minimally viable, the basis of competition shifts from content to user experience. A consumer has no reason to switch from Spotify to Apple or Amazon to access original content since they all carry the same stuff, so they opt for whoever provides the best curation and build personalized playlists on that service, locking themselves in over time:

Source: Spotify Investor Day Presentation (Jun 2022)

Benedict Evans has this line about how all the questions that matter for Netflix are about Hollywood, not technology. But in music streaming, where content is a shared commodity, technology drives differentiation.

Streaming music isn’t such a great business in isolation but it creates a captive base on which Spotify can layer low marginal cost revenue streams. The idea that Spotify could leverage its users to disintermediate labels was a popular bear thesis for Warner 3 years ago. But investors have come to see that the game theory of mutual assured destruction prevents either party from bypassing the other (a streaming service isn’t competitive without labels’ catalogs and artists won’t put up with a label that doesn’t distribute on the market leading streaming service). I think this is the right take. But that doesn’t mean Spotify can’t extract value from the labels in other ways. For instance, with all the first party engagement data they have on an audience that is primed to discover new tracks, Spotify has spun up a marketplace that labels can use to promote their artists’ music to new fans. Rather than attempt to disintermediate labels or fight for greater share of subscription revenue, Spotify can grab margin by charging them for access to its subscriber base. Wary of tying their fortunes to a single, ever dominant platform and keenly aware that marketing can be an easy stream acquisition tool when used by one player but an industry tax when used by all, the labels might be reluctant to spend too heavily on Spotify. But they all care about stream share and it only takes one defector to break the dam. There are signs of traction. Marketplace revenue has grown from €20mn to €160mn in just 3 years and has been the primary driver of Spotify’s music gross margin gains.

Podcasting is the other hopeful money maker. Since getting into podcasts in 2018, Spotify has spent $1bn on content, with just $200mn of annual revenue and enormous losses to show for it. But while podcast industry ad revenue is a small ($2bn) ,it is growing rapidly (500%+ since 2018) industry and with Original and Exclusive content representing a disproportionate share of the Top 100 podcasts on its service, Spotify is taking share. So management thinks that by growing ad revenue on a largely fixed cost base they can eventually get podcasting gross margins to 40%-50% (vs. 27% for the overall company today). Podcasting, like music, is audio but the useful life of content is shorter and the business model has more in common with video streaming, where content is once again a vector of differentiation and the usual perpetual inflated bidding concerns apply. But augmenting music with exclusive podcast content should better retain existing users and also draw new ones, some of whom will convert to Premium subscribers, emboldening Spotify to demand a greater share of revenue. Of course, the matter of who has more bargaining isn’t specific to Spotify but pertains to any service that commands a massive audience, including (no, especially) TikTok, where discovery plays such a central role and I imagine labels’ mature catalogs have far less value. Though then again, the labels will argue that they are getting a growing share of revenue from emerging channels like social media, fitness tech, and gaming, making them less reliant on Spotify. I don’t have a strong intuition about who will find themselves in a better position to demand better economics 5-10 years from now.

Owning the consumer relationships gives Spotify options on new sources of value creation (podcasts, audiobooks, NFTs??), but getting those options in the money means spending boatloads to acquire subscribers and content. The music labels more or less just free ride off that. While Spotify YOLOs into new TAM, their 3 largest suppliers clip low variance cash flows.

The labels pitch themselves as tech savvy, forward looking operators with a firm pulse on the trends. But let’s be real. When P2P sharing heaved the industry into existential crisis, the best the incumbent labels could do was fight back with lawsuits. It fell upon Apple and then Spotify to push the industry to its current profitable equilibrium. That’s not to say the record labels aren’t more attentive to new ways of capitalizing on talent (with all monumental changes over the last 10 years, how could you not?) but for the most part I see them as gold mines of IP protected by sharp legal teams, managed by A&R folks whose art for discovering talent is increasingly subsumed by the technicalities of scrapping engagement data that is concentrated in a handful of streaming platforms. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing! That the big 3 absorb most of the industry’s profits despite contributing the least to its innovation tempo is maybe the most compelling testimony of how durable their legacy advantages may be. It’s hard for me to gain that much conviction in any single consumer facing app that monetizes through fickle and scare attention (Netflix isn’t just competing against linear TV but Fortnite, TikTok, Instagram, etc. TikTok was born just 5 years ago and today has Facebook quaking in fear). The record labels are a safer bet that whatever the next big social experience turns out to be, music will play an important role.

Disclosure: At the time this report was posted, accounts managed by Compound Insight LLC owned shares of AMZN. This may have changed at any time since.