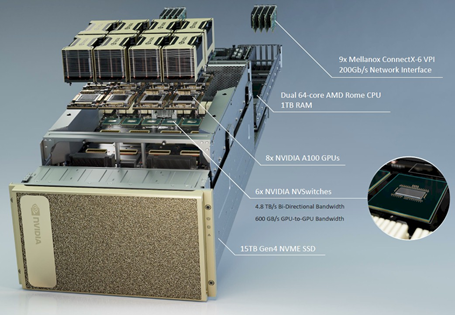

I left Part 1 [1]talking about how the demands of high performance compute had outgrown the chip and were increasingly being handled at the level of the data center. There are two different but related planes of inter-connection inside a datacenter: within a single server (scale-up) and across servers (scale-out). In a scale-up configuration a server, like Nvidia’s monster DGX-2, might have up to 8 GPUs connected1 [2] together and treated by CUDA as a single compute unit. In scale-out, servers are connected to an an Ethernet network through network interface cards (NICs, which can be FPGA, ASIC, or SoC-based) like those from Mellanox, so that data can be moved around and shared across them. Those servers can act in concert as a kind of unified processor to train machine learning models.

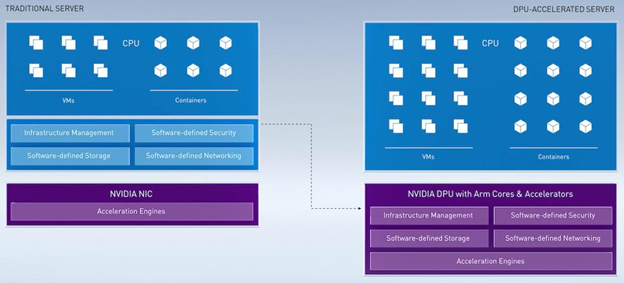

As the basic compute unit moves from chips to datacenters, a different kind of processor, sitting beside a CPU, is needed to handle the datacenter infrastructure functions that are increasingly encoded in software, which is where Data Processing Units (DPU, also called “SmartNIC”) come in. Described by Nvidia as a “programmable data center on a chip”, DPUs from Mellanox take the low-level networking, storage requests, security, anomaly detection, and data transport functions away from CPUs. 5 years from now Nvidia thinks every data center node could have a DPU, as embedding security at the node level plays to the zero trust security paradigm and offloading infrastructure processes from CPUs accelerates workloads. Something like 30% of cloud processing is hogged by networking needs. CPUs that should be running apps are instead managing the infrastructure services required to run the apps (a single BlueField 2 DPU provides the same data center services as 125 x86 cores). Just as Nvidia’s GPUs have CUDA software running on top, DPUs have complementary APIs and frameworks (DOCA SDK) for developers to program security and networking applications.

In short, GPUs accelerate analytics and machine learning apps, CPUs run the operating system, and DPUs handle security, storage, and networking. These chips are the foundational pillars of Nvidia’s data center platform.

This idea of treating the datacenter as a unified computing unit isn’t new. Intel framed the datacenter opportunity the same way 5 or 6 years ago, as it complemented its CPUs with interconnect (Omni-Path Fabric2 [3], silicon photonics), accelerators (FPGAs and Xeon Phi), memory (Optane), and deep learning chips (Nervana, Habana). Its Infrastructure Processing Unit (IPU) is analogous to Nvidia’s DPU. AMD is progressing along a similar path, complementing its EPYC x86 server CPUs and GPUs with networking, storage, and acceleration technology from its pending $35bn acquisition of Xilinx, mirroring the GPU/CPU/Networking stack that Nvidia is building through its acquisitions of Mellanox and, soon, ARM.

ARM sells a family of instruction set architectures. You can think of an instruction set as the vocabulary that software uses to communicate with hardware, the “words” that instruct the chip to add and subtract, to store this and retrieve that. In the decades leading up to the 1980s, instruction sets had gotten increasingly ornate as it was believed that the more complex the instruction set (i.e., the more intricate the vocabulary), the easier it would be for developers to build more powerful software. Also, the more complex the tasks that could be executed, the more developers could economize RAM [4], an expensive resource at the time.

During the 1980s, some engineers at UC Berkeley, bucking the trend of the preceding 3 decades, whittled down instruction complexity, creating an alternative to CISC appropriately called a Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC). A RISC processor required up to 50% more instructions to accomplish a given task vs. a CISC, but each of those instructions, by virtue of their relative simplicity and standard size, could be executed 4x-5x faster3 [5]. Most PCs in the 1980s used simple instructions that could have been handled by RISC processors, which were more power efficient to boot. But for whatever reason the PC ecosystem coalesced around Intel’s x86 CISC architecture instead. It required a new compute platform – the explosion of mobile, IoT, and other portable devices – for RISC’s more power efficient architecture to take off.

Over the last decade, ARM’s attempts to extend beyond mobile and into PCs and datacenters have gone nowhere. In 2011, it launched a 64-bit version of its instruction set, which in enabling CPUs to access more memory [6] at the expense of power, could address the PC and server market in earnest. AMD briefly experimented with a novel “ambidextrous” strategy to design pin-compatible4 [7] x86 and ARM chips. This didn’t take, and after futzing around with other ARM-based server chips for workstations and entry-level servers (down market from where Intel’s enterprise-grade Xeon X5 processor dominated), AMD reversed course and doubled down on x86.

Applied Micro went after the high-end of the server market in 2014 with its X-Gene family of multi-core ARM processors, but it too failed to gain traction (the X-Gene IP eventually sold to Ampere Computing, which is making another run at ARM servers today). Cavium (now owned by Marvell) and Qualcomm gave it a go but were forced to retreat. Nvidia and Samsung also launched and then cancelled their ARM data center initiatives. High profile ARM processor start-up, Calxeda, closed shop [8] in 2013 after raising $100mn [9] of funding. ARM and various other chip designers and OEMs pushed a new hardware standard, Server Base System Architecture, that attempted to resolve the profusion of incompatible ARM-based systems into a common platform for developers to efficiently build on. In 2016, ARM projected that by 2020 it would claim 25% of server CPU shipments [10]. Of course, here we now are, and ARM is nowhere near that level, with x86 still comprising ~99% [11] share.

The software ecosystem that has congealed around x86 over the past 30 years is a massive barrier to overcome. Even Nvidia’s management admits that the “vast majority” of enterprise workloads will run on x86 CPUs for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, interest in ARM servers has been rekindled in recent years, as ARM cores have gotten more powerful and energy efficiency assumes greater importance. Changes in software development are also propelling ARM adoption. Monolithic applications are increasingly being factored into container-based microservices and the technology behind that stuff – major Linux distributions, hypervisors, and Kubernetes – runs on ARM as well as x86. In 2018, AWS introduced custom built Graviton processors [12], which used ARM cores to power EC2 cloud workloads. Microsoft too is rumored to be designing ARM-based processors for servers powering Azure cloud services. A few years ago, Cray announced that it would be licensing Fujitsu’s ARM processor for exascale (10^18 calculations per second) computing. Ampere’s 7nm ARM processor is being evaluated by Microsoft Azure and will be deployed in Oracle’s Gen 2 cloud [11] (Oracle is an Ampere investor).

Given ARM’s significant developer base and the growing share of compute cycles claimed by hyperscalers who are designing ARM CPUs internally, maybe it’s not so off base to think that ARM CPUs might come to command a significant minority of cloud workloads in 5-10 years.

You may recall that Softbank acquired ARM for $32bn in 2016 as part of a paradigm-shifting vision of shipping 1 trillion AI-infused ARM chips over 20 years (Project Trillium). Under Softbank’s ownership, ARM’s license and royalty revenue growth slowed to a standstill5 [13] and EBITDA margins collapsed from mid-40s to low-teens as massive R&D investments in IoT/AR/computer vision have thus far yielded no accompanying revenue (minus the IoT services group, ARM’s EBITDA margins are ~35%). Meanwhile, Softbank’s vision of winning 20% of the server market failed to come to fruition. Having made little progress against its original goals, Softbank agreed to sell ARM for not much more than what it paid 4 years earlier ($40bn, implying a 6% annualized return)6 [14].

But this acquisition is not just about bringing ARM into the datacenter. It is also an opportunity for NVIDIA to push its growing collection of IP to ARM’s vast ecosystem, which includes 15mn developers (vs. CUDA’s ~2mn developers) and ships 22bn chips per year (vs. Nvidia’s 100mn). With ARM, Nvidia can offer a consistent platform on which developers can train their AI models with Nvidia’s GPUs in the cloud and distribute those models to devices running on ARM CPUs. To enable what it refers to as an “iPhone moment” for IoT, where trillions of small form factors have AI baked into them, management has talked about fusing low power CPUs with Nvidia’s high performance compute. As Jem Davies, General Manager of ARM’s Machine Learning Division, put it [15]:

With over eight billion voice assistive devices. We need speech recognition on sub-$1 microcontrollers. Processing everything on server just doesn’t work, physically or financially. Cloud computing bandwidth aren’t free and recognition on device is the only way. A voice activated coffee maker using cloud services used ten times a day would cost the device maker around $15 per year per appliance. Computing ML on device also benefits latency, reliability and, crucially, security.

As it machetes its way through a thicket of regulatory sign offs, Nvidia is pinky swear promising to keep ARM’s architecture open and neutral, even as it develops its own ARM-based processors, like the ones embedded in its Bluefield family of DPUs. I think Nvidia is really serious about its open posture though as they have so much more to gain by selling proprietary AI technology alongside a flourishing and variegated universe of ARM CPUs than by treating ARM as a closed and proprietary asset. Nvidia is commoditizing its CPU complement but also, with Grace, its first ARM-based data center CPU7 [16], showcasing the best version of what that complement could be when tightly integrated with Nvidia’s GPU.

Also, if Softbank is intent on divesting ARM, then Nvidia – which has used ARM as the CPU engine for its Tegra SoCs since 2010 and a few years ago made CUDA and all its AI frameworks available to ARM [17] – might want to control this critical IP than risk having it fall into the hands of a buyer who might fiddle with licensing terms and compromise the ecosystem. As Nvidia’s own legal sagas with Intel, Qualcomm, and Samsung demonstrate, licensing agreements can be fraught with challenges.

To recap, AI-driven demands of high performance compute have outpaced Moore’s Law. The chip alone is insufficient. Tackling ever more compute intensive workloads will require a full stack of technology…not just CPUs, GPUs, DPUs, and the interconnects that transfer data across them, but the software running on top of those processors and the frameworks running on top of that software. Through CUDA-X AI, its deep learning stack, Nvidia offers SDKs that introduce visual/audio effects (Maxine), accelerate recommendation engines (Merlin), and power conversational chatbots (Jarvis), which in turn are customized for different industry verticals.

For instance, Nvidia has a full stack automotive offering that enables over-the-air software updates, eye tracking, blink frequency monitoring, driverless park, and autopilot, among other applications. Wal-Mart uses [18] GPUs and Nvidia-supported open-source libraries to forecast 500mn store-item combinations every week. The National Institutes of Health and Nvidia together developed AI models to detect COVID-related pneumonia cases with 90% accuracy. Nvidia has pretrained models and frameworks specific to industry verticals so that enterprises, with some last mile training, can start using AI right away.

In addition to the providing the technology to train neural nets, Nvidia also has a specialized GPU (T4) and software (Triton) to run inference8 [19], which has gotten harder for standard CPUs to do at low latency as ML models have complexified.

And Nvidia is not just using software to bind customers to its chips; it’s in the early stages of monetizing it directly, affirming that “over time, we expect that the software [revenue] opportunity is at least as large as the hardware opportunity”9 [20]. GeForce Now converts gaming GPUs into a subscription revenue stream. AI Enterprise, a suite of AI software that runs on VMware’s vSphere and is accelerated by Nvidia’s GPUs, is sold to enterprises for ~$3,600 per CPU socket + a recurring maintenance fee. Nvidia earns subscription fees on Base Command, software that enables teams of data scientists to manage and monitor AI workflows, and Fleet Manager, a SaaS application for deploying AI services edge servers (you might imagine training an AI model in the cloud and deploying it to a fleet of vehicles). Omniverse is being sold to enterprises as a server license with a per user fee. Volvo, Mercedes, Audi, Hyundai, plus a number of EV manufacturers run ADAS software and OTA updates on top of DRIVE, and Nvidia shares in the revenue that Mercedes generates from selling software and services to its connected vehicle owners. According to management, “with software content potentially in thousands of dollars per vehicle, this could be a multibillion revenue opportunity for both Mercedes and NVIDIA”10 [21]. It’s easy to imagine similar deals in manufacturing, retail, agriculture, and just about any industry with connected edge devices. So Nvidia’s journey may bear some resemblance to the one taken by Apple, which offered SDKs to encourage developer adoption with the near/medium-term aim of selling more hardware and the longer-term aim of monetizing through software and services.

But that layers of software abstractions makes it easier to develop and run AI workloads doesn’t mean the GPUs at the base layer are optimal for all of them. There is some amount of GPU real estate that is tuned to graphics, which is a somewhat different kind of problem than AI. In this this interview with anandtech.com [22], legendary microprocessor engineer Jim Keller describes GPUs as optimized for lots of small operations whereas AI acceleration demands fewer but bigger and more complex ones (h/t LibertyRPF [23]):

GPUs were built to run shader programs on pixels, so if you’re given 8 million pixels, and the big GPUs now have 6000 threads, you can cover all the pixels with each one of them running 1000 programs per frame. But it’s sort of like an army of ants carrying around grains of sand, whereas big AI computers, they have really big matrix multipliers. They like a much smaller number of threads that do a lot more math because the problem is inherently big. Whereas the shader problem was that the problems were inherently small because there are so many pixels.

There are genuinely three different kinds of computers: CPUs, GPUs, and AI. NVIDIA is kind of doing the ‘inbetweener’ thing where they’re using a GPU to run AI, and they’re trying to enhance it. Some of that is obviously working pretty well, and some of it is obviously fairly complicated. What’s interesting, and this happens a lot, is that general-purpose CPUs when they saw the vector performance of GPUs, added vector units. Sometimes that was great, because you only had a little bit of vector computing to do, but if you had a lot, a GPU might be a better solution.

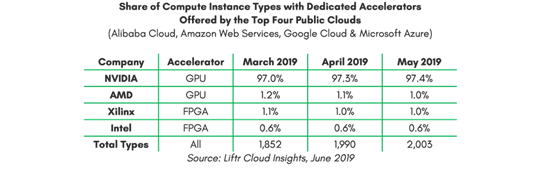

This “inbetweener” state perhaps offers a competitive opening in the data center for chips like Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) and Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) that can better execute certain specialized tasks. In return for superior performance, ASICs give up flexibility. Nvidia’s general purpose architecture can be configured in software rather than hardware, rendering it suitable for a wider range of applications and machine learning models than fixed function chips. FPGA logic gates can be re-programmed after manufacturing but only with significant upfront engineering costs and using arcane low-level hardware description languages [24]. Xilinx realizes ~$300mn of revenue in the data center and is growing at a respectable though much slower pace than Nvidia, who generates ~$8bn. The addressable market for FPGAs may expand with inference at the edge, where Xilinx purports superior performance vs. GPUs. But Nvidia is also intent on grabbing edge inference workloads as it embeds acceleration technology into ARM CPUs.

An integrated CPU/GPU/FPGA solution perhaps strengthens AMD’s position in the datacenter. But then again Intel tried the same thing. They thought combining their Xeon server CPU and Altera’s FPGA, first within the same package and then on a single chip, would result in 2x+ performance gains at lower cost for ~30% of cloud workloads. I think a lot of this rode on Altera leveraging Intel’s then leading node technology. With Intel slipping several generations behind TSMC, Altera – now Intel’s “programmable solutions” segment – has seen its revenue decline (vs. expectations of 7% growth) and profits plummet. FPGA share of cloud workloads are just low-single digits.

The other possible threat to Nvidia comes from its hyper-scale cloud customers – AWS, Azure, GCP account for around half of Nvidia’s data center revenue (the other half come from enterprise sales) – designing custom ASICs. TensorFlow is optimized for Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), so if everyone committed to TensorFlow as their machine learning framework and shifted workloads to GCP to take advantage of TPUs, that could be a problem for Nvidia. Following Google’s lead, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon are now also designing their own AI accelerators. AWS Inferentia chips are custom designed for ML inference, an area where Nvidia, which has historically focused on training, has a less mature position (AWS also has a custom chip, Trainium, specialized for deep learning training). In addition to hyperscalers, there’s a bunch of well funded AI chip designers that have in recent years – Graphcore, SambaNova, Arteris, Cerebras, Blaize, Habana Labs (acquired by Intel). It’s possible that one of them establishes a strong presence in edge inference, a fragmented space where the entry barriers are lower and Nvidia is less present, builds out a software stack there and backs into training.

But still, the CUDA software stack and the developer ecosystem ensconce Nvidia’s hardware in a thick layer of insulation. Even if a competing chip architecture is somewhat technically superior, I would imagine that most developers will still default to the tried and true stack that gets them to market faster. I’m also inclined to lean on the “ecosystem” defense for why ARM will hold up against competitive inroads from RISC-V, though I’m not prepared to die on this hill. RISC-V is an open source RISC ISA that is freely available to chip designers, who might otherwise pay millions in licensing fees and recurring royalties for ARM designs. Some engineers gripe that ARM’s RISC ISA has evolved along the same as the CISC ISA that came before, gradually complexifying to the point where calling it a “reduced” instruction set no longer seems appropriate. RISC-V is a cleaner, simpler alternative whose base of just 47 instructions can be complemented by optional extensions, enabling all sorts of custom performance-power permutations tailored to the profusion of specialized workloads pertaining to AI, augmented reality and IoT, among others. Samsung is using RISC-V [25] cores for RF processing and image sensing in its flagship 5G smartphones. Western Digital and Seagate has RISC-V processors [26] running in disk drives to handle mounting computational demands. Alibaba is designing RISC-V-based [27]CPUs to underpin its cloud and edge infrastructure and I’m sure all its hyperscaler peers are developing RISC-V processors too. Even Nvidia uses RISC-V microcontrollers [28] in its GPUs. RISC-V may even one day underpin competing GPUs. A “group of enthusiasts” are bolting graphics extensions [29] to the RISC-V base to create a “fused CPU-GPU ISA” for mainstream applications. This smells a lot like Intel’s failed Larrabee project, though I’m sure the comparison is unfair for any number of technical reasons I don’t understand. RISC-V’s toolchain and ecosystem is not as mature as ARM’s but it’s getting there. Maybe RISC-V becomes the hardware equivalent of Linux or maybe it underpins a constellation of processors that run alongside ARM and Nvidia GPUs, whose software moats prove impenetrable…who can really say? But if you’re going to own Nvidia stock, this is something to be aware of.

As for the cloud service providers…well, their commitment to Nvida seems as strong as ever. AWS is collaborating with Nvidia, combining its ARM-based Graviton CPUs with Nvidia’s GPUs for EC2 instances; Microsoft uses Nvidia AI for grammar correction in Word and is optimizing DeepSpeed, an open source deep learning training library [30] that is progressing towards training models with trillions of parameters (vs. GPT-3’s 175bn parameters), for Nvidia Tensor Cores and CUDA kernels. The A100 GPU has been adopted by the major clouds faster than any architecture in Nvidia’s history. Even as chip rivals have experienced sequential declines the last few quarters (“cloud digestion”), Nvidia’s hyperscale revenue continues to grow q/q. Management estimates that in 2-3 years Nvidia GPUs will account for 90% of inference compute in the cloud. My intuition is that AWS and Microsoft have the critical mass to build out their own AI solutions – the chips, software, apps, development environment – and could even tailor those solutions to industry verticals (Microsoft is already building industry specific clouds, with industry tailored workflows and data models). But at least for now, Nvidia’s dominant position in HPC acceleration looks secure.

Nvidia supplies the foundational technology to just about every major technology trend – autonomous driving, edge computing, gaming, computing, VR, AR, machine learning, big data, analytics. Management likes to say that “everyone will be a gamer”, slyly gesturing to the inevitability of an immersive metaverse. The demand for accelerated processing is insatiable. Since Nvidia launched its Volta architecture just 4 years ago, the compute intensity required to train the largest machine learning model has gone up 30x. Nvidia claims that the complexity of ML models is doubling every 3-4 months. Everyone basically understands this. Still, Nvidia’s history can be a jarring reminder of how hard it is to get technology bets right, even obvious ones. At almost every point in Nvidia’s history over the last 20 years, there was a compelling story about mainstream graphics penetration, programmable compute, mobile, and workstations. As an Nvidia shareholder, you could have been directionally right about all of them and still had your ass handed to you at various times.

One year the chipset business is 15% of revenue and growing more than 30%. Two years later, poof, it’s gone. In its place, Nvidia created a new family of co-processors (Tegra) that now generates 2x as much revenue as the defunct chipset business did at its peak. But nobody, not even management, predicated how Tegra would succeed. It’s hard to overstate how important mobile generally and Tegra specifically was to Nvidia’s roadmap circa 2010. But mobile was a bust for Nvidia and its own line of Android tablets and smart TV boxes, marketed under the SHIELD brand, didn’t take either. The real market for Tegra turned out to be cars, though even here Nvidia overestimated the traction of self-driving vehicles. The Tesla architecture was a slow-growing side show to Tegra, doing just $100mn of revenue. Today, with AI on its way to pervading everything, the business delivers ~twice what Tegra generates. When Nvidia began exploring IP licensing 5-6 years ago, an investor may have gotten excited about the prospect of sticky, pure margin licensing revenue, only to be disappointed when this venture went nowhere.

Tegra and especially Tesla would eventually prove to be significant growth drivers, but things took longer than expected as Nvidia was pre-occupied with various mishaps from 2008 to 2010. Nvidia bet on Windows instead of Android for mobile; overshot, then undershot inventory; came late to 40nm and late to market with its groundbreaking Fermi architecture. Quadro was crushed by the retraction in corporate spending. Nvidia’s share of notebook GPUs fell from the low-60s to around 40%. From fy08 (ending January) to fy10, gross margins slumped from 46% to 34%, EBIT profits fell from $836mn to -$99mn. Investors wondered why Tegra, after years of investment, generated just ~$200mn of annual revenue and with R&D expenses up 523% from fy08 to fy11 on a 14% revenue decline during the same period, Nvidia was starting to look like a playground run by engineers too busy valiantly pushing the bleeding edge to pay any mind to financial viability. But it turned out that Nvidia could have its cake and eat it too. By 2011, most of these issues were resolved. Nvidia released a flurry of Fermi chips and GeForce regained share. Quadro’s end markets recovered.

For the first half of its life, Nvidia was more or less a widget vendor whose fortunes turned on inventory planning. It was a trading stock for semiconductor experts who had deep insight into specs and inventory cycles. But I think that has become less true, with 2/3 of Nvidia’s engineers now working on software, building full stacks geared to the indefatigable AI mega-trend. This isn’t at all like pumping out commodity chips to meet a fixed quantum of cyclical demand. The thirst for compute is unquenchable. Sure, supply/demand imbalances will revisit the industry from time to time – there are currently chip shortages in gaming, and GPU demand from crypto mining has been so strong in recent quarters that Nvidia carved out a separate line of crypto mining processors (CMPs) to prevent miners from siphoning off limited GeForce supply – which matter if you’re playing the quarters….but these imbalances don’t have the existential overtures they once did because the software stack and ecosystem support around Nvidia is so mature today. At 25x revenue, Nvidia trades like a high flying SaaS and maybe it should.

There’s a lot going on at Nvidia and it can be easy to get lost in the arcana of feeds and speeds. But the long-term bull case for Nvidia basically boils down to this: AI is going to be ubiquitous and requires GPUs for training and inference. Nvidia makes GPUs with the most complete software stack and developer buy-in. Its AI platform is integrated with all the hyperscale clouds, runs behind corporate firewalls11 [31], will be carried to edge datacenters and devices, and tailored to various industries. The company is foundational to our AI-laden metaverse future. Making sense of Nvidia’s valuation demands that you keep things as simple and as broad as that.

There is a time and place for grandiose convictions. In 2005, pounding the table with: “Nvidia’s going to be the dominate stack for the biggest compute trends” would have been prescient but also, I submit to you, absurd and unjustified. But any claim more specific than that would have mandated that you blow out of the stock. In 2007, the thesis that Nvidia’s MCP and Windows Vista would catalyze mainstream GPU adoption would have broke 2 years later. The same is true if in 2009, following a ~60%-70% decline in Nvidia’s stock over the previous 2 years, you believed mobile was the next gargantuan opportunity. In 2012, many analysts still believed that Windows RT (Windows 8 for ARM) was going to be a the third major operating system, alongside iOS and Android, and presented a vast growth opportunity for Tegra. No one at the time was really talking in earnest about megatrends like machine learning, big data, and “the metaverse” that would really come to make the difference.

The same could be said about Microsoft. Investors see where Microsoft is trading today and berate themselves for not buying in 2011 when the stock was trading at 12x earnings. But Microsoft is not only a different bet today than it was in 2011, but different in ways that were unknowable at the time. Central to most long pitches back then was that desktop Windows was a resilient cash gushing platform, that mobile wasn’t a real threat for such and such reasons or that Microsoft would carry its dominance of PCs into mobile or something. But MSFT has 10x’ed over the last decade for reasons (mostly) unrelated to desktop Windows and despite its failure in mobile. You can’t even latch onto the catch-all “culture” argument – i.e., “nobody knows what the future holds but this company has an adaptive culture and a great leadership team, so they will figure it out”. This was still the Ballmer era. No reasonable person looking at Microsoft should have cited “dynamic culture and management” as part of their pitch. Not even Microsoft knew what it was going to be at the time. We tend to focus on whether an investment decision turned out to be right or wrong rather than the degree of conviction justified by what was knowable at the time.

When researching a stock, I often mentally snap myself back to an earlier date and ask what a reasonable thesis could have been. But this is also a tricky exercise with no right answers. You need to embrace uncertainty, but at what point are you just taking a flyer? When would an investment not only turned out to be right in retrospect but justified by the facts at the time? You should be able to at least loosely sketch a path from here to there – describing how one building block might lead to another and then another – but the reasonableness of that path is a subjective assessment. There are bad math and bad facts, but there are also valid differences of opinion on a stock like NVDA that seem practically irresolvable, grounded as they are in differences in hard wiring and life experiences that we each bring to bear in our analysis of complex entities maneuvering in a complex system.

(If you want to learn more about the semiconductor industry and Nvidia, the following people are much smarter than me about such things: @BernsteinRasgon [32], @GavinBaker [33], @FoolAllTheTime [34])

Disclosure: At the time this report was posted, Forage Capital owned shares of MSFT and AMZN. This may have changed at any time since.